Nicholson’s table regulator clock at the British Museum

March 3rd, 2017share this

Images copyright British Museum

The British Museum was founded in 1753, the year of William Nicholson’s birth. I have evidence of at least two of his visits to the museum. The first was as part of his research for the 1783 edition of A Critical Review of the Public Buildings, Statues, and Ornaments, in and About London and Westminster. Then in January 1790, Nicholson deposited the journals of the Count de Benyowsky with the museum for safekeeping. He might have been rather delighted to know that one of his own creations would end up there too.

In 1958, one of Nicholson’s clocks was acquired by the British Museum as part of the Ilbert Collection - the most important collection of horology ever achieved by a private collector.

Courtenay Ilbert (1888-1956) was a civil engineer and he acquired the clock from a dealer called Clowes on 17 March 1938. He paid £20 for this 1797 regulator clock, a sum at the top end in comparison to the prices that Ilbert paid for other clocks from that period.

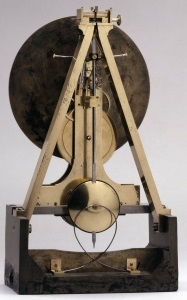

I recently enjoyed a visit behind the scenes with a curator of horology, Oliver Cooke, who had very kindly got the clock working for me. Previously I had seen the picture of the Nicholson’s clock on the British Museum website but had not registered the dimensions, and was surprised at how large it is.

Height: 57 centimetres

Width: 30.75 centimetres

Depth: 17.3 centimetres

The clock is described in David Thompson’s book Clocks as “an interesting example of a rather unassuming case which in reality conceals a movement of a most unusual and interesting design.”

The British Museum describes it as " SATINWOOD CASED EIGHT-DAY BRACKET TIMEPIECE WITH GRAVITY ESCAPEMENT AND CENTRE-SECONDS. Bracket timepiece; eight-day; gravity escapement; round silvered-metal dial with centre-seconds; satinwood case with moulded arched hood; glazed panels to front and sides surmounted by brass flaming vase finials. TRAIN-COUNT. Gt wheel 180" Click here for the full description.

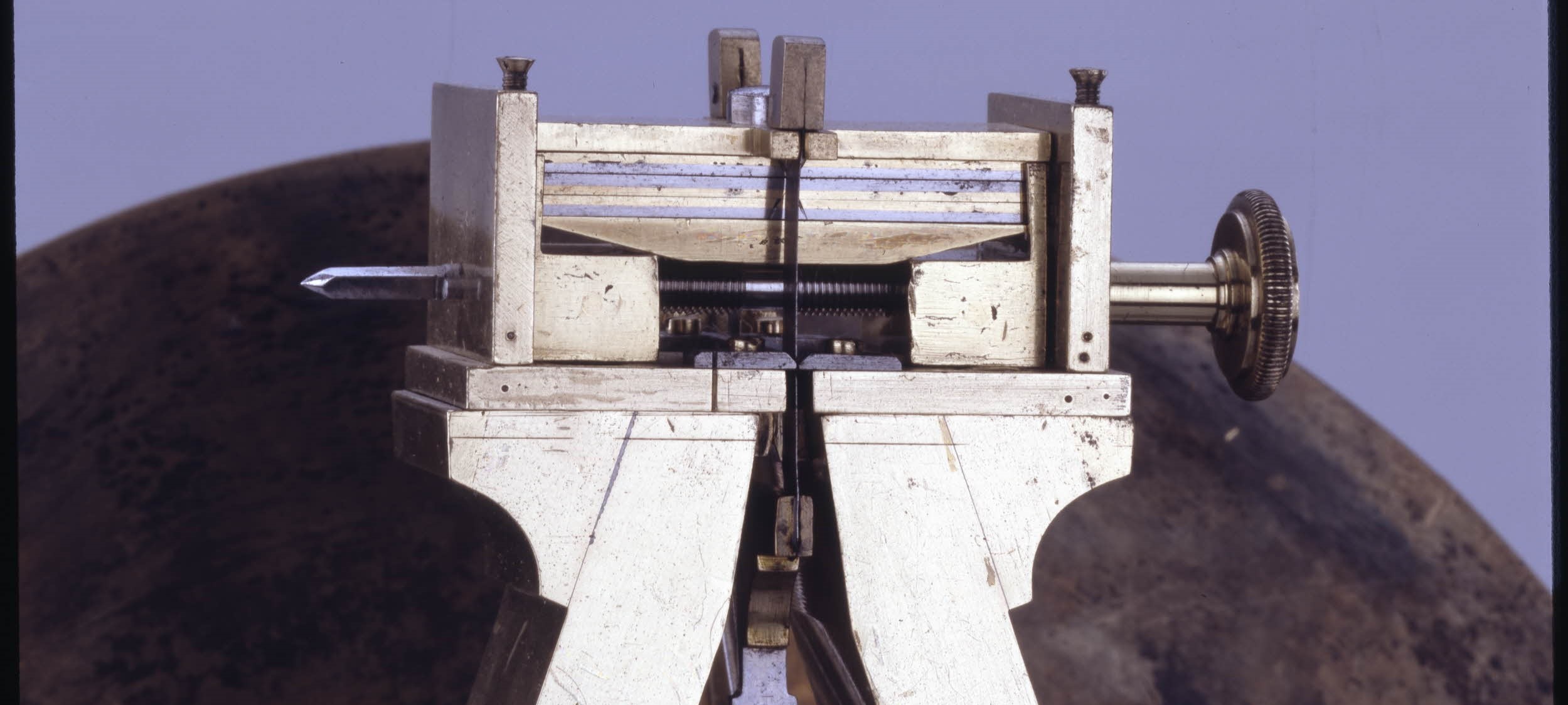

The delicate mechanism for this 8-day clock rests upon a rather unprepossessing lump of steel which acts to stabilise the clock and to support the pendulum and the movement.

The plain steel pendulum rod would expand or contract with changes in temperature, but at the top Nicholson has built an ingenious mechanism with bi-metallic strips to compensate for the changes in temperature.

“Nicholson’s big solid design is going in the right direction – and it is good to see someone outside the clock-making tradition trying something different,” said Oliver Cooke. “It was clearly an attempt to make a precision timepiece, and you can see original thinking – even if Nicholson has not got it quite right.”

Nicholson’s name is engraved on the dial where the name of the commissioner/designer would usually appear: Wm Nicholson f 1797

More information can be found in:

Clocks by David Thompson, British Museum Press, London 2004.

Precision Pendulum Clocks, The Quest for Accurate Timekeeping, by Derek Roberts, Schiffer Pub Ltd, Atglen, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 2003

#4

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Support independent bookshops, and order a copy from Bookshop.org

Order