17 and 20 October - In Conversation with William Nicholson and the UCL Ucell clean energy team at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival

August 28th, 2020share this

It is very exciting to announce that William Nicholson (1753-1815) will be making an appearance at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival alongside the UCL hydrogen fuel cell demonstrator!

Saturday 17 October 2020,

2.30 – 3.30 pm – Live event in St George’s Gardens, London, WC1N 6BN at thewest end.

Tickets £8 (£6 concs) – Clickhere for details.

Tuesday 20 October 2020

2.30 – 3.30pm – Online event, via the Bloomsbury Festival at Home

Tickets £5 – Clickhere for details.

How the discovery of electrolysis has changed the future’s energy landscape

August 25th, 2020share this

A guest blog by Alice Llewellyn from UCell, the electrochemical outreach group at UCL

Shortly after the invention of the battery in the form of a voltaic pile by Alessandro Volta in 1800, William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840) discovered that water can be split into its constituent elements (hydrogen and oxygen) by using electrical energy.This phenomena is termed electrolysis and is the process of using electricity to produce a chemical change. Electrolysis was a critical discovery, which shook the scientific community at the time. It directly demonstrated a relationship between electricity and chemical elements. This fact helped scientific legends – Faraday, Arrhenius, Otswald and van’t Hoff develop the basics of physical chemistry as we know them.

Fast forward to today, and we are faced with one of the greatest challenges – climate change. This effect has accelerated the search for alternative fuels and energy storage devices fin order to decarbonise the energy sector. Burning fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) for energy is the main cause of climate change as it produces carbon dioxide gas which leads to a greenhouse effect and the warming of our atmosphere.

A huge contender for alternative fuels is hydrogen. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe. However, it does not typically exist as itself in nature and is most commonly bonded to other molecules, such as oxygen in water (H2O). This is where electrolysis plays a key role. Electrolysis can be used to extract hydrogen from the compound which can then go on to be used as a fuel. Moreover, if a renewable source of energy is used (for example wind or solar) to provide the electricity required to split the water, then there is no carbon footprint associated with this hydrogen production.

Hydrogen can then be used in fuel cells to produce electricity. Fuel cells are electrochemical energy devices, they convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy without any combustion. The way in which a fuel cell works is in fact the reverse process of electrolysis. In a fuel cell, hydrogen is split into its protons and electrons which then react with oxygen to produce water, electricity and a little bit of heat. As the only side product of this reaction is water, fuel cells are a very clean way to produce electricity.

Energy from renewable sources (wind, solar…) is intrinsically intermittent. Depending on the season or time of the day more or less energy is produced. To make sure the supply of energy is secure and stable, energy needs to be stored when an excess is produced and later fed back into the grid when needed. Water electrolysis offers grid stabilization. When a surplus of energy is available, e.g. during the day when the sun is shining, some of this energy is used to produce hydrogen. This hydrogen can then easily be stored in tanks. Whenever more energy is needed, e.g. when it is dark, hydrogen is taken from tanks and fuelcells are used to release the energy stored in the hydrogen.

Not only can hydrogen be used for grid stabilisation, but this can also be used to transform the transport sector, which contributes to around a quarter of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions. Fuel cell vehicles are one of the solutions that have been adopted to tackle this problem and are classed as zero-emission vehicles (only water comes out of the exhaust).

In 2019, London adopted a fleet of hydrogen-powered double decker buses – a world first! As more people start to learn about this technology, more fuel cell vehicles can be spotted on our roads.

Without the discovery of electrolysis by Nicholson and Carlisle in 1800, it might not be possible to produce pure hydrogen for these applications in such an environmentally-friendly way, making the fight against climate change a more difficult task.

*

About our guest author Alice Llewellyn

Following a masters project synthesizing and testing novel battery negative electrodes, Alice Llewellyn, started her PhD project in the electrochemical innovation lab at UCL, primarily using X-ray diffraction to study atomic lattice changes in transition metal oxide cathodes during battery degradation. Alice co-runs the electrochemical outreach group UCell.

UCell is a group of PhD and masters students based at University College London, who are passionate about hydrogen, clean technologies and electricity storage and love sharing their knowledge and experience to the general public through outreach, taking their 3 kW fuel cell stack to power stages, thermal cameras and, well, anything that needs powering! In a time of a changing energy landscape, they aim to show how these technologies are starting to become a regular feature in our everyday lives.

#30

Termites tuck into Nicholson’s Journals in Bombay in 1859

August 9th, 2020share this

Here is an extract from the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, from Monday 28th November 1859 telling of a sad fate for Nicholson’s Journal.

“It is with much regret that the Committee have to inform the Society that the White Ants, which infect the Town Hall throughout, have found their way into the Library, and destroyed many of the books.

This was first discovered in September 1858, and since that there have been several incursions … during which 12 works or 33 volumes have been destroyed, and 12 works or 38 volumes slightly injured; fortunately those which have been destroyed have chiefly consisted of Novels, the others have been works in the classes of Classics and Chemistry; - “Nicholson’s Journal” however, has severely suffered.”

#30

Solving the C18th puzzle of scientific publishing

July 13th, 2020share this

A guest blog, by Anna Gielas, PhD

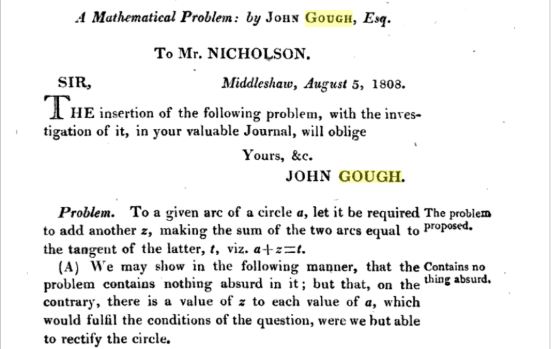

William Nicholson made Europe puzzle. Continental men of science translated and reprinted articles from his Journal on Natural Philosophy,Chemistry and the Arts on a regular basis—including the mathematical puzzles that Nicholson published in his column ‘Mathematical Correspondence’.

When Nicholson commenced his editorship in 1797, his periodical was one of numerous European journals dedicated to natural philosophy. Nicholson was continuing a trend that had existed on the continent for over a quarter of century. But at the same time, Nicholson was committing to a novel form of philosophical communication in Britain. The British periodicals dealing with philosophy and natural history were linked with learned societies. Besides the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, numerous philosophical societies in other British towns, including Manchester, Bath and Edinburgh, published their own periodicals. The London-based Linnaean Society, which had close ties to the Royal Society, also printed its transactions.

Nicholson’s editorship did not have any societal backing. He did not conduct his periodical in a group, but by himself. These circumstances made his Journal something different and novel—maybe even revolutionary. In the Preface to his first issue, Nicholson confronted the very limited circulation of society and academy-based transactions and their availability to the ‘extreme few who are so fortunate’. He made it his editorial priority to reprint philosophical observations from transactions and memoirs—to make them accessible to a wider audience.

Considering his friendship with the radical dramatist Thomas Holcroft and his collaboration with the political author William Godwin, we can think of Nicholson’s editorial priority in political terms: he wished to democratize philosophical communication. Personal experiences could have played a role here, too. Nicholson appears to have initially harbored some admiration for the Royal Society and its gentlemanly members. But he did not become a Fellow due to his social background. Whether he considered his inability to be part of the Society a social injustice is not clear. But this experience likely played a role in his decision to edit and reprint from society transactions.

There seems to be a political dimension to Nicholson’s editorship—yet the sources available today do not allow any straight-forward reading of the motives for his editorship. He did not present his editorship as a political move. Instead, he used the rhetoric of his contemporaries—the rhetoric of utility: ‘The leading character on which the selections of objects will be grounded is utility’, he wrote in his Preface. The Journal was supposed to be useful to ‘Philosophers and the Public’.

Nicholson had acquired the skills necessary for editing a periodical over many years. It seems that his organizing role in a number of societies and associations was particularly helpful to hone such abilities—for example, his membership at the Chapter Coffee House philosophical society. In mid-November 1784, Nicholson and the mineralogist William Babington were elected ‘first’ and ‘second’ secretaries of the society. During the gathering following his election, Nicholson appears to have raised 13 procedural matters for discussion and action. According to Trevor Levere and Gerard Turner, Nicholson ultimately ‘made the meetings much more effective and disciplined’.

His organizing role brought and kept him in touch with most of the Chapter Coffee House society members which enabled him to expand and affirm his own social circle among philosophers. So much so, that some of the society members would go on to contribute repeatedly to Nicholson’s Journal. As the ‘first’ secretary, Nicholson gained experience in steering a group of philosophers and experimenters towards a productive and lasting exchange—a task similar to editorship.

Nicholson was skilled in fostering and maintaining the infrastructure of philosophical exchange. His contemporaries were well aware of it and sought his support on a number of occasions. Among them was the publisher John Sewell who invited Nicholson to become a member of his Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Here, Nicholson and Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and Vice-President of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, had one of two conflicts.

Philosophical societies in late eighteenth-century London tended to have presidents and vice-presidents, committees and hierarchies. More often than not, these hierarchies mirrored the members' actual social ranks. As an editor, outside of a society, Nicholson was free from hierarchies. He could initiate and organize philosophical exchange as he saw fit—which likely made editorship attractive to him.

For Nicholson who was almost constantly in financial difficulties, editing was also a potential source of additional income. After all, the same month the first issue of his Journal came out, Nicholson's tenth child, Charlotte, was born. But the Journal did not become a commercial success. Yet, he continued it over years, until his health deteriorated. Non-material motives seem to have outweighed his monetary needs.

His journal was an integral part of Nicholson’s later life—particularly when he no longer merely reprinted pieces from exclusive transactions. After roughly three years since the first issue appeared, his Journal began to turn into a forum of lively philosophical discourse. In the issue from August 1806, for example, he informed his contributors and readers of the ‘great accession of Original Correspondence’, which he—whether for the reason of ‘utility’ or democratizing philosophy—published in later issues rather than foregoing publication of any of them.

Outside of Britain, the Journal was read in the German-speaking lands, Russia, Netherlands, Scandinavia, France and others. Nicholson made Europe puzzle indeed. He united geographically as well as culturally and socially distant individuals, bringing European men-of-science closer together.

Further reading:

Anna Gielas: Turning tradition into an instrument of research: The editorship of William Nicholson (1753–1815),

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1600-0498.12283

#29

Book Review: Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World

February 9th, 2020share this

At the age of 15, my sons were fairly obsessed with sportand under pressure to work towards impending exams. It is hard to imagine sending them to theother side of the world by sea with the East India Company at that age, as wasthe case with young William Nicholson. It is hard to imagine, the seafaring bustle of the Thames when shipswere built of wood, sails were sewn by hand and sailors could be seen hangingfrom the rigging as he boarded his first Indiaman in 1768.

Nowadays there are daily flights from London to Guangzhou (Cantonto Nicholson) with a journey time of less than ten hours. In 1768, the journeywould take several months and (not being any sort of sailor) it is hard toimagine the life on board – the routines, the food, the highs and lows – that wouldhave been Nicholson’s life.

Fortunately, under my Christmas tree this year was a copy ofPeter Moore’s Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World, abook tracing the history of this bark’s life from before it was launched in1764 through its early life in the coal trade between London and the NorthEast, along its famous journey to the South Seas to observe the Transit ofVenus with Captain Cook and Joseph Banks, and finally her role in one of thegreatest invasion fleets in British History.

Moore paints such a vivid picture of the bark and the charactersaboard, the environment in port or at sea, and the political and economicsetting – that it was a very enjoyable read and easy to imagine Nicholsonpassing the Endeavour in the Thames or the Channel as they set sail in the sameyear.

It was charming to meet the young Sir Joseph Banks when hewas full of fun and enthusiasm, eagerly collecting thousands of botanical specimens- for Nicholson’s encounters with Banks two decades later had left me with theimpression of a grand but arrogant and entitled character.

As a young man crossing the equator for the first time, andwithout the means to pay a fine to avoid the experience, Nicholson will havehad to partake in the traditional dunking ceremony which was described in greatdetail when Endeavour crossed in October.

While Cook’s South Sea discoveries have been told manytimes, Moore then traces the history of this vessel further on through a periodof sad neglect into a new role during the revolutionary years as part of the Navalforce which amassed in New York Harbour in 1776.

I was quite carried along by the tale of this doughtyworkhorse, and really enjoyed Moore’s telling of the international political backdrop.

You don’t need to be a historian of sailing to enjoy this historyof an enlightenment hero of the seas.

#28

William and Catherine Nicholson's Twelve Children (UPDATED)

January 23rd, 2020share this

Image courtesy of Tawny van Breda via Pixabay

Rather frustratingly, William Nicholson Jr (1789-1874) refers to a book in which the births of all the Nicholson children are listed ‘in minute detail’ – I wonder if this still exists?

Meanwhile, I think it might be a good idea to share what Ido know, and maybe someone else might stumble across this post one day and be ableto help complete the picture.

Sarah Nicholson

Born 21 February 1782

Married John Edwards RN, 2 October 1811

Died 7 March 1866, Torpoint.

Ann Nicholson

Born 20 April 1784

Died 22 March 1874, Plympton

William Nicholson

Born 15 March 1786

Bapt 9 April 1786

Died in infancy

Robert Nicholson

Born c1787

Died May 1814, Calcutta / Bengal.

Mary Nicholson

Born 28 November 1787

Married to Hugh Macintosh (1775-1834) on 31 December at Fort St George,Madras, India.

Gave birth to William Hugh Macintosh (1807-1840) on 27 December 1807

Died very soon after childbirth 1807/1808, India.

William Nicholson

Born 31 October 1789

Married Rebecca Brown, 18 August 1815

Son, John Lee Nicholson, born c1817

Died July 1874, Hull.

John Nicholson

Born c1791

Author of The Operative Mechanic andBritish Machinist.

Died in Australia (TBC).

Isaac Nicholson

Possibly born around 1793, if age 15 in 1808, when he was a midshipman aboard the David Scott.

Catherine Nicholson

Bapt 28 September 1794

Married Robert Hicks (1777-1832), 27 May 1813

Married Rev James Sedgwick (1794-1869) in 1838

Died before 1869

Charlotte Nicholson

Born 16 April 1797

Playmate of Mary Godwin (Shelley)

Married Henry Augustus Miller, 11 May 1815

Gave birth to Louisa Jane Miller, 1824 (Cuddalore?, East Indies)

Gave birth to Maria Miller, c1826 (India)

Married Richard Backhouse (?-1829), 15 January 1827

Died 7 July 1869

Martha Mary Nicholson

Born 24 May 1799

Baptised 4 July 1799

Playmate of Mary Godwin (Shelley)

This leaves one child still to be identified - Potentially a twin!

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order