It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

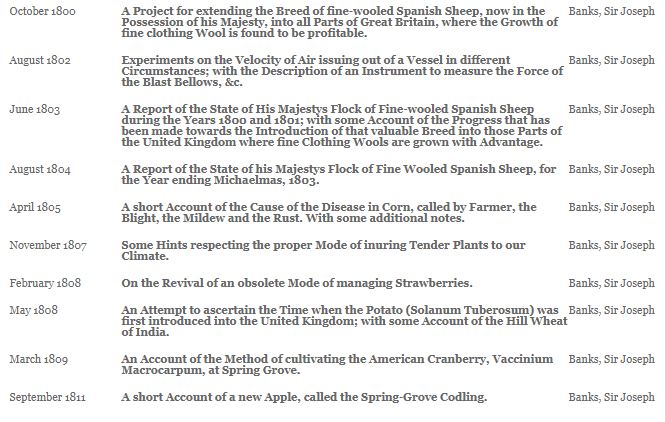

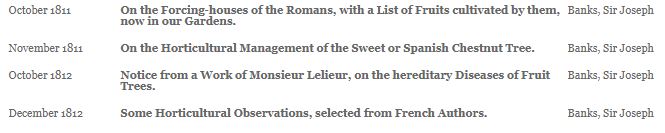

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

Invention #1 - Nicholson’s Hydrometer

January 15th, 2018share this

A hydrometer is a device for measuring a density (weight per unit volume) or specific gravity (weight per unit volume compared with water). It was also called an aerometer, a gravimeter or a densimeter.

On 1 June 1784, Nicholson wrote to his good friend Mr. J. H. Magellan with: ‘A description of a new instrument for measuring the specific gravities of bodies’.

According to Museo Galileo, hydrometers date back to Archimedes and the Alexandrian teacher Hypatia, but the second half of the nineteenth century saw the design of several types which were well-used in industry of which “the better-known models include those developed by Antoine Baumé (1728-1804) and William Nicholson (1753-1815)”.

Nicholson’s paper, which does not seem to be accompanied by a drawing, was published the following year in the Memoirs of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (London: Warrington, 1785) 370–380, and can be accessed via Google Books

In the first edition of Nicholson’s A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, Nicholson wrote an article about the hydrometers invented by Baumé – one for spirits and one for salts - which had never been used in this country, but never mentioned his own earlier invention.

In June 1797, Nicholson published a translation of a paper that had been read in France at the National Institute by Citizen Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveau (1737-1816), and then published in the Annales de Chimie. Nicholson points out that ‘this translation is nearly verbal’ as he finds himself writing about his own invention.

Comparing Nicholson’s hydrometer with that designed by Fahrenheit which he described as ‘not fit for the hand of the philosopher’, Guyton de Morveau says:

“The form which Nicholson gave some years ago to the hydrometer of Fahrenheit, rendered it proper to measure the density of solids. At present it is very much used. It gives, with considerable accuracy, the ratio of specific gravity to the fifth decimal,water being taken as unity. … It does not appear that any better instrument need be wished for in this respect.”

Of all of Nicholson’s inventions, this one still bears his name and is called Nicholson’s hydrometer today. Examples can be found in several museums, and it is possible to purchase a modern version for use in school experiments for just a few dollars.

The Oxford Museum of the History of Science kindly showed me their Nicholson’s hydrometer from 1790.

Others can be found at:

HarvardUniversity Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

St.Mary's College in Notre Dame, Indiana

The VirtualMuseum of the History of Mineralogy (Private collection)

Sadly, I couldn’t find a video online with a demonstration of Nicholson's hydrometer being used. If anyone knows of one, or feels the urge to produce one, I would love to share it on this website.

#20

Publication update: Is this the closest I will get to appearing alongside Liam Neeson?

December 17th, 2017share this

OK, that got the ladies’ attention …!

I have been so busy checking facts, dates and references that, with my brain firmly in the eighteenth century, I forgot to update the website with our publication plans.

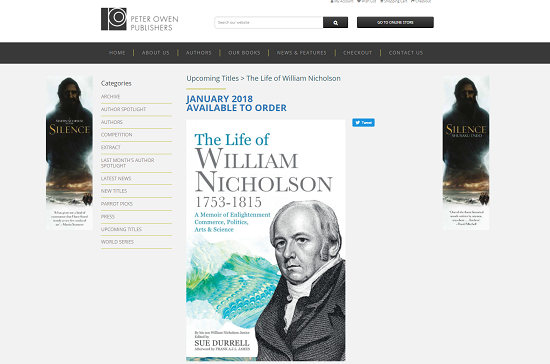

Firstly, I am delighted to say that I was signed up by PeterOwen Publishers, one of the leading independents. I was the last non-fiction writer to besigned before Peter Owen passed away at the grand age of 89. He established his publishing house in 1951 and accumulated a record-breaking ten Nobel prize-winners over sixty-five years in business.

Miraculously, they were the first publishing house that I approached but, like those of you who know Nicholson already, they instantly recognised that our hero was in need of a biography.

In Peter Owen’s obituary in the Telegraph, he was described as ‘bewilderingly eclectic’ and a ‘champion of the obscure’ – given that Nicholson and I are little known (for now), that seems like a pretty good fit. I shall enjoy being obscure in good company.

The Life of William Nicholson was written 150 years ago and until now, has been available only to historians via a visit to the Bodleian Museum (MSS. Don. d. 175, e. 125), but it is now available to order online and will be in shops in the new year.

So, what has this got to do with Liam Neeson? Well I couldn’t help being just a little thrilled to see his brooding presence either side of Mr Nicholson on the cover of Nobel prizewinner Silence by Shusaku Endo (a recent film by Martin Scorsese).

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

Just don’t mention that there isn’t a movie (yet)!

#18

If museum image fees are "killing art history” what hope for historians of science and commerce …

November 11th, 2017share this

Image Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay

Well done to the group of art historians who wrote to The Times on 6 November:

“The fees charged by the UK’s national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished. Such fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge that is the very purpose of public museums and galleries. Fees charged for academic use pose a serious threat to art history: a single lecture can cost hundreds of pounds; a book, thousands.”

A full copy of the letter (and more recent developments) can be found on the website www.arthistorynews.com.

As someone who uses images as a daily basis for marketing, I am used to being able to licence stock images (photographs or drawings) from websites such as Istockphoto or Shutterstock for a reasonable fee, and was shocked to find out how much some museums wished to charge, how complicated the fee structure can be, and how inconsistent the pricing structure is across various national institutions.

Initially, I had been keen to include a large number of illustrations in my modern biography of Nicholson - hoping to bring some potentially dry scientific subjects to life - but I soon had to modify my aspirations.

By way of example, when writing this blog on Nicholson’s clock, which is in the British Museum but not on public display, I was only allowed to include the three images provided by the Museum under the Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence, “an internationally recognised licence recommended by one of the Directives we are expected to follow as a public sector body.”

However, the museum did not have photographs of some interesting and unique aspects of the clock including a close up of the inscription “William Nicholson / 1797” and a side view showing the fusee mechanism.

While I was permitted to take photographs, and video, for my personal use during the visit – I was not allowed to use these on the blog, as

“… you can certainly use your own images for ‘private and non-commercial purposes’ but I’m afraid you are not permitted to publish these images.

This allows us to maintain the quality of representation of our objects, keep a record of what is used and avoid any complications regarding future copyright.

The Museum’s Visitor Regulations regarding personal photography is:

8. Film, photography and audio recording

8.1 Except where indicated by notices, you are permitted to use hand-held cameras (including mobile phones) with flash bulbs or flash units, and audio and film recording equipment not requiring a stand. You may use your photographs, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/2011-11-14%20Visitor%20Regulations%20FINAL.pdf

The image rights team kindly offered to “easily arrange new photography for £85 + VAT (30 day turnaround but often much faster)”. How they might incur such costs was a mystery to me, and I did not bother to ask whether this was per photograph.

This seems to go against the British Museum’s object of:

The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be FREELY accessible.

Given that Nicholson’s clock is not on public display, one might have thought they would see the benefit of some broader exposure online – at no cost to the public purse.

In thinking about what to include in book, I am faced with this pricing structure for scholarly and academic books:

Total combined print run and download units (prices per image ex-VAT):

Up to 500: £30

501 – 1,000: £40

1,001 – 2,000: £50

2,001 – 3,000: £60

My initial plan to include up to eight images, in order to properly detail the design and mechanics, would set me back £400 if the print run is between 1,000 and 2,000. Somehow, I doubt that Neil MacGregor has this problem when choosing his next set of 100 hundred objects.

There is a big difference between the commercial value in the photograph of Nicholson’s clock’s fusee and an iconic sculpture such as the Discobolus, of which the British Museum sells replicas for £2,500.

I should think that the trustees of the British Museum would have a better understanding than most of the fact that many niche historical books have only a limited customer base, but are nonetheless extremely valuable in terms of the spread of knowledge and understanding.

#17

Book Review – A walk on part in ‘The Shape of Water’

October 22nd, 2017share this

As the marketing guru John Hegarty said (and I am fond of quoting) “Do interesting things, and interesting things will happen to you” – and how true this has been. Little did I know where my first visit to the Wedgwood Museum would lead … to Tasmania.

William and Catherine Nicholson’s daughter Mary (1787 - 1807/8) married a Captain with the East India Company, Hugh Macintosh (1775 - 1834) at Fort St George, in Madras, India. Sadly, she died very shortly after giving birth to William Hugh Mackintosh (1807-1840) in December 1807.

Hugh Macintosh eventually travelled to Van Diemen‘s Land (now Tasmania) where, in partnership with Peter Degraves, he was one of the founders of The Cascade Brewery Company in 1824.

Back in the summer 2016, I received an email from the author Anne Blythe Cooper in Tasmania in regard to this connection. As it was the middle of the day, and the time difference seemed favourable, I decided to give her a ring – only to find that she was in Yorkshire.

The subject of interest for Anne was Sophia (the wife of Peter Degraves), about whom little was known. Like the women in Nicholson’s life, and many at that time, so little was recording in writing that they are almost invisible today.

Anne was also planning a trip to Anglesey, which meant that she would be almost passing Staffordshire. Seizing the opportunity, we arranged to meet and spent many hours trying to fill plug holes in the histories of the Degraves and Macintosh/Nicholson family connections.

In The Shape of Water: Imagined fragments from an elusive life: Sophia Degraves of Van Diemen's Land, a work of historical fiction, Anne Blythe-Cooper tells the fascinating story of the life, hardships, imprisonments and eventual success of the Degraves family through the eyes of Sophia.

Knowing very little of the history of the Van Diemen's Land, renamed as Tasmania in 1856, I found it a fascinating read. The descriptions of the societal, entrepreneurial and environmental conditions are very vivid, and it was delightful to read William and Mary Nicholson’s first appearances in a work of historic fiction (as far as I am aware).

I was interested to learn of the Tasmanian tiger (sadly declared extinct in 1936) and Mount Wellington, the development of the brewery and the theatre. Peter Degraves, sounds like a nightmare of a husband – but that certainly makes the book an enjoyable read.

So far it is only available via Forty South Publishing in Tasmania, but as the early story is set in London and many of the characters have English heritage – it deserves to be published in the UK too.

For now, it can be ordered via via Forty South Publishing - The Shape of Water by Anne Blythe-Cooper.

#16

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order