FutureLearn MOOC - Humphry Davy: Laughing gas, literature and the lamp.

October 4th, 2017share this

A MOOC (for those of you like me who did not know what this was) is a ‘massive open online course’, and Lancaster University and the Royal Institution of Great Britain are hosting one about Humphry Davy which will start on 30 October 2017.

The course will run for four weeks. Learners will typically spend three hours per week working through the steps, which will include videos (filmed on location at the Royal Institution), text-based activities and discussion, and quizzes. Learners will be guided at all stages by a specialist team of educators and mentors. It's entirely free to participate, and no prior knowledge of Davy is required.

Humphry Davy was a good friend of William Nicholson and they were both keen disseminators of knowledge, so would encourage you to spread the word to anyone who might be interested.

In 1797 young Davy had ‘commenced in earnest his study of natural philosophy,’ but this ‘soon gave place to that of chemistry’ and in his note book he recorded that his first experiments ‘were made when I had studied chemistry only four months, when I had never seen a single experiment executed, and when all my information was derived from Nicholson’s Chemistry, and Lavoisier’s Elements.’ (style='"Times New Roman",serif;' (Davy and Davy, The Collected Works,1839.)

Then in the Spring of 1799, Davy made contact with Nicholson sending two articles to include in A Journal of Natural Philosophy and the Arts, both of which appeared in the May edition:

- Experiments and Observations on the Silex composing the Epidermis or external Bank, and contained in other Parts of certain Vegetables.

- Introductory to the Experiments contained the subsequent Article, and on other Subjects relative to the Progress of Science.

There is much more to tell about their relationship, but now is not the time, so let’s get back to the MOOC …

This FREE course is intended for anyone with an interest in Humphry Davy, or early nineteenth century literature, science, or history. It will explore some of the most significant moments of Davy's life and career, including his childhood in Cornwall, his work at the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol and the Royal Institution in London, his writing of poetry, his invention of his miners' safety lamp and the controversy surrounding this, and his European travels. The course will also investigate the relationships that can exist between science and the arts, identify the role that science can play in society, and assess the cultural and political function of science.

Free course – open to all - sign up today at

http://www.futurelearn.com/courses/humphry-davy

#14

Change time at the Royal Exchange

September 27th, 2017share this

Image: The Royal Exchange, London c1750, Courtesy of Wikigallery

The following sentence in The life of William Nicholson by his Son caused me to Google ‘Change Time’ to see what this referred to:

‘And daily congregated in the shop after change time six or eight or more of the leading merchants to gossip over politics and the affairs of the day …’

Rather amusingly, an explanation came up from our very own Mr Nicholson in The British Encyclopedia, 6 vols of 1809, which I thought worthy of sharing due to the severity of the punishments threatened:

In 1703, the following notice appeared in the public papers: "An act of the Lord Mayor and Court of Alder men is affixed at the Exchange, and other places in this City, by which all persons are prohibited coming upon the Royal Exchange to do business before the hours of twelve o'clock, and after the hour of two, till evening change: Wherein it is further enacted, that for a quarter of an hour before twelve the Exchange bell shall ring, as a signal of change time ; and shall also begin to ring a quarter of an hour before two, at which time the change shall end : and all persons shall quit it, upon pain of being prosecuted to the utmost, according to law. That the gates shall then be shut up, and continue so till evening change time; which shall be from the hours of six to eight from Lady-day till Michaelmas, and from Michaelmas to Lady-day from the hours of four to six; before and after which hours the bell shall ring as above said. And it is further enacted, that no persons shall assemble in companies, as stock jobbers, &c. either in Exchange Alley, or places adjacent, to stop up and hinder the passage from and to the respective houses thereabouts, under pain of being immediately carried before the Lord Mayor, or other Justice of the Peace, and prosecuted."

For an explanation of Lady Day, click here

For an explanation of Michaelmas, click here.

#13

Holcroft, Nicholson and the C18th gig economy

September 3rd, 2017share this

While the phrase ‘gig economy’ has been all over the mainstream media recently with the publication of the Good Work: The Taylor Review of modern working practices, the expression has been around for nearly a decade and insecure working arrangements have been around for centuries. In 2015, The Financial Times chose the expression for its FT 2015 Year in a Word, by Leslie Hook.

Leslie traced the expression back to the height of the financial crisis in 2009, ‘when the unemployed made a living by gigging, or working several part-time jobs, wherever they could’ with the word ‘gig’ emanating from jazz club musicians in the 1920s.

I could not help noting the similarities with life for many in the 18th Century as I re-read the Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft by William Hazlitt. Holcroft was a good friend of Nicholson, and his early employment history included time as a shoemaker, a stable lad at Newmarket, and as a chorister where he earned the nickname ‘the sweet singer of Israel’.

Holcroft headed for London where, like many young people today, he ‘felt the effects of poverty very severely’ and ruminated on what might have resulted from a good education. He was getting so desperate for work that he was heading to the office which recruited soldiers for the East India Company when he bumped into a friend who mentioned an opportunity with a travelling theatre company in Dublin. Then, for several years, he traipsed about the country in search of one opportunity after another before finally settling in London as a writer and dramatist.

Nicholson too was no stranger to the gig economy, having first worked for Josiah Wedgwood on a 'consultancy assignment' to Amsterdam to investigate financial irregularities with the Dutch sales agency. This had led to an employed position in Amsterdam, but only for a discrete project and so Nicholson had to return to London in search of work.

When young William Nicholson came to lodge with Holcroft at Southampton Buildings in around 1780, Holcroft subcontracted bits of writing to him. He also tried to persuade Nicholson that ‘at least as much revenue could be obtained from literary publications, as from any of the objects … of his thoughts.’

Over 25 years, Nicholson successfully built a steady income from writing, translating and publishing. But, with a large family to feed, he also took several gigs on the side. Projects included consulting on technical issues, sometimes as an early patent agent, acting as Secretary to the Chapter Coffee House Society and the General Chamber of Manufacturers. Then in the mid-1800s, he took on assignments as a civil engineer for a couple of water supply projects.

Unfortunately, like many who operate in the gig economy today, Holcroft and Nicholson did not set aside enough of their incomes during the good times to provide for ill-health in their old age.

The gig economy is not such a new phenomenon, but it does remind us that workers did not always enjoy the social safety nets that we often take for granted and are comparatively recent developments in the history of employment:

•1908 – old age pension introduced for men over 70

•1938 – paid holiday introduced

•1940 – old age pensions introduced for women

•1948 - the NHS was introduced.

#12

World Helicopter Day – On Aerial Navigation

August 20th, 2017share this

I have just noticed that 20 August is World Helicopter Day, and on a recent visit to the helicopter museum in Weston-Super-Mare (the World's Largest Dedicated Helicopter Museum) with my father, a former helicopter engineer, I spotted a reference to the three papers by Sir George Cayley in Nicholson’s Journal.

‘On Aerial Navigation’ was published in three parts:

Nicholson’s Journal, November 1809

Nicholson’s Journal, February and March 1810

I have since seen this described online, by Mississippi State University, as:

"Arguably the most important paper in the invention of the airplane is a triple paper On Aerial Navigation by Sir George Cayley. The article appeared in three issues of Nicholson's Journal. In this paper, Cayley argues against the ornithopter model and outlines a fixed-wing aircraft that incorporates a separate system for propulsion and a tail to assist in the control of the airplane. Both ideas were crucial breakthroughs necessary to break out of the ornithopter tradition."

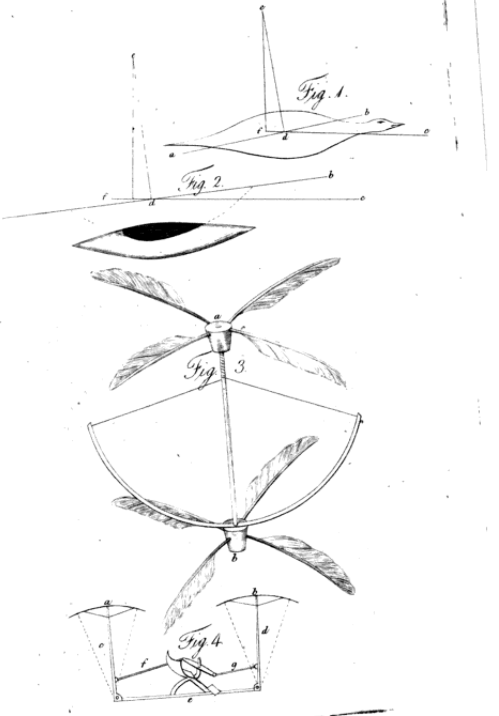

This sketch from the November 1809 paper.

If any historians of aeronautic developments would like tocontribute a guest blog on the significance of Cayley’s papers, please email us at

info@nicholsonsjournal.com.

#12

Josiah Wedgwood’s advice on international trade negotiations …January 1786

August 3rd, 2017share this

When Josiah Wedgwood was invited to chair the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he remembered the able young man who had served him well in the Netherlands in the 1770s, and invited William Nicholson to serve as his secretary.

International trade was a fundamental concern of the Chamber, as it is today, and it was interesting to come across this letter online which had been auctioned by Bonham’s in 2004.

Wedgwood wrote to the Rt Hon William Eden who was about to depart to France to negotiate a trade treaty, with this simple request:

“With regard to our particular manufacture, we only wish for a fair and simple reciprocity, and I suppose (but I speak without any authority) that our Manchester & Birmingham friends would be willing to give & take in the same way...”

http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11288/lot/144/?page_lots=8&upcoming_past=Past

#11

Book review: The Enlightened Mr Parkinson

July 28th, 2017share this

As we near publication of the Life of William Nicholson by his son, I find myself scanning the shelves of every bookshop to see whether much, if any, space is given to Georgian biographies. I was delighted to come across this biography in prime position on the New Releases shelf: THE ENLIGHTENED MR. PARKINSON – The pioneering life of a forgotten English surgeon by Cherry Lewis.

Parkinson identified a specific type of shaking palsy and it is this mental health condition for which his name is recognised today, but the biography tells a broader story of his work in general medical practice, his involvement in social and political reform, and his interest in fossils and geology. He was one of the founders of the Geological Society in 1807.

I particularly enjoyed the way that the author has explained the background at a time of tumultuous and constant change occasioned by wars, political upheaval, societal advances, medical and scientific discoveries. This is done in a very accessible way which ensures that the book will be just as enjoyable for a reader who is not intimate with that period of his life, between 1755 and 1824.

Parkinson’s life coincided pretty well with William Nicholson (1753-1815). They would certainly have met at the Geological Society, which Nicholson joined on the suggestion of their mutual friend Anthony Carlisle, if not in the mid-1790s when Parkinson was a member of the London Corresponding Society with Nicholson’s good friend Thomas Holcroft.

Parkinson submitted four papers to Nicholson’s Journal:

October 1807 - Nondescript Encrinus, in Mr. Donovans Museum.

March 1809 - On the Existence of Animal Matter in Mineral Substances.

May 1809 - On the Dissimilarity between the Creatures of the present and former World, and on the Fossil Alcyonia.

January and February 1812 - Observations on some of the Strata in the Neighbourhood of London, and on the Fossil remains contained in them.

THE ENLIGHTENED MR. PARKINSON – The pioneering life of a forgotten English surgeon

By Cherry Lewis, published by ICON

http://www.iconbooks.com/ib-title/the-enlightened-mr-parkinson/

#10

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order