2017 Hull & 1804 a 'Half-mad' story of South Sea Whaling

May 1st, 2017share this

Image: Robert Salmon [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The second interesting discovery via the Hull Maritime Museum was sparked by their display of the history of whaling. Although the whalers departing from Hull headed mainly for the Arctic Waters, there was some mention of the south sea fisheries, and I was pointed towards a most useful resource: the British Southern Whale Fishery (BSWF) Database.

Run by the University of Hull, the online database supplies details of actual voyages, and the people involved in the BSWF between 1775 and 1859.

The British southern whale fishery, commenced in 1775 and its trade was almost exclusively carried out from London. Initially it focused primarily in the mid to south Atlantic; by the mid-1790s it had moved to the Pacific and Indian Oceans and was limited to the areas off the coasts of Africa, South America and the east coast of Australia, but by 1815 the trade had spread to the wider Pacific.

The trade was often referred to as the South Seas Whale Fishery, and it was some unfortunate project related to this with Thomas Pitt, Baron Camelford II, (the Half-Mad Lord) which was at the root of Nicholson’s financial problems in later life.

Camelford’s project involved an investment in two whaling ships, believed to be called the Experiment and the Wilding which were secured by a ‘reputable merchant’ called Mr Rogers.

The Wilding is listed on the database; it sailed in 1803 and returned in 1805 under the command of John Borlinder.

Unfortunately, there are a number of vessels called the Experiment, but none of these sailed in the southern seas around 1804, the year in which Camelford was shot in a duel and died.

If you can contribute any information on the Experiment or the Wilding, Mr Rogers or John Borlinder, or their connection with homas Pitt, Baron Camelford II, please get it touch: info@nicholsonsjournal.com.

#7

2017 Hull City of Culture / 1777 Wedgwood Shipping

April 13th, 2017share this

Imagecourtesy of MyLearning.org © Hull Museums

Our son is working in Hull, so with it being Hull’s year as the City of Culture we decided to tread the tourist trail on a recent visit and enjoyed a tour of the Maritime Museum.

I am always struck by how busy sea ports appeared in paintings from the seventeenth and eighteenth century and this image of Hull’s first port particularly caught my eye. It was built between 1775 and 1778, creating the largest port in Britain. The dates rang a bell as I knew that Wedgwood was shipping his pottery to Amsterdam from Hull just the year before.

In May 1777, Nicholson was working as Josiah Wedgwood’s agent in Holland where he was responsible for negotiating the transfer of the pottery business to Lambertus van Veldhuysen. Nicholson wrote to Thomas Bentley on 20 June 1777 that van Veldhuysen:

‘expects all future orders to be expeditiously forwarded & shipped at Hull at the charge of Mr Wedgwood, or at London when haste is required.’

Van Veldhuysen’s agent in Hull was Thomas Horwarth.

1777 was also the year that the Trent and Mersey canal was completed, allowing Wedgwood to convey his pottery to Hull via the waterways and thereby reduce the number of breakages.

By 1783, over 13 million pieces of pottery and earthenware were being exported via Hull (not all Wedgwood).

#6

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787)

March 20th, 2017share this

In December 1780 in the Chapter Coffee House near St Paul's Cathedral, several men led by the Irish chemist Richard Kirwan decided to meet fortnightly to discuss ‘Natural Philosophy, in its most extensive signification’.

The membership of the group grew steadily, and meetings took place in a variety of locations including the Baptist’s Head Coffee House. William Nicholson joined in 1783 and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

Nicholson’s copy of the minutes of the society, until 1787 when it folded, are in Oxford’s Museum of the History of Science and it was wonderful to be able to inspect them recently.

Compared to other philosophical societies of that time, especially the Lunar Society which had been meeting in the Midlands since 1765, this group seems little known – partly because it never had any name.

In 1785 it was agreed that the group would have no formal name when Kirwan ‘affirmed that the society not being desirous of that kind of distinction which arises from name or title were so far from giving any sanction or authority to the names used by their secretaries that the original determination in this respect was that the society should not have a name.

Fortunately the minutes do include a most interesting list of 35 members (the total number of members over the life of the society was 55).

Mr Alex Aubert (1730-1805), Austin Friars, 26

MrWilliam Babbington(1756-1833)

MrAndrewBlackhall (?-?), Thavies Inn, Holborn

DrWilliamCleghorn(1754-1783), Haymarket, 11

DrJohnCooke(1756-1838)

DrAdairCrawford(1748-1795), Lambs Conduit Street, 48.

MrJean-Hyacinthde Magellan(1722-1790), Nevilles Court, 12

MajorValentineGardiner(1775-1803)

DrWilliamHamilton(1758-1807)

MrJamesHorsfall(-d1785), Inner Temple.

DrJohnHunter(c1754-1809), Leicester Square

DrCharlesHutton(1737-1823)

MrWilliamJones(1746-1794), Inner Temple

DrWilliamKeir(1752-1783), Adelphi

MrRichardKirwan(1735-1812), Newman Street, 11

DrWilliamLister(1756-1830)

MrPatrickMiller(1731-1815), Sackville Street, 17

MrEdwardNairne(1726-1806), Cornhill, 20

MrWilliam Nicholson(1753-1815)

DrGeorgePearson(1751-1828)

DrThomasPercival(1740-1804)

DrCharles William Quin(1755-1818), Harmarket, 11

DrJohnSims(1749-1831), Paternoster Row, 11

MrBenjaminVaughan(1751-1835), Mincing lane

MrAdamWalker(c1731-1821), George Street, Hannover Square

DrWilliam CharlesWells(1757-1817), Salisbury Court

MrJohnWhitehurst(1713-1788), Bolt Court, 4

DrJohnWatkinson(1742-1783), Crutched Friars, 22

Honorary members

DrMatthewBoulton(1728-1809), Birmingham

MrRichardBright(1754-1840), Bristol

MrJamesKeir(1735-1820), Birmingham

DrRichardPrice(1723-1791), Newington Green

Rev'd DrJosephPriestley(1733-1804), Birmingham

MrJamesWatt(1736-1819), Birmingham

MrJosiahWedgwood(1730-1795), Etruria

Further information

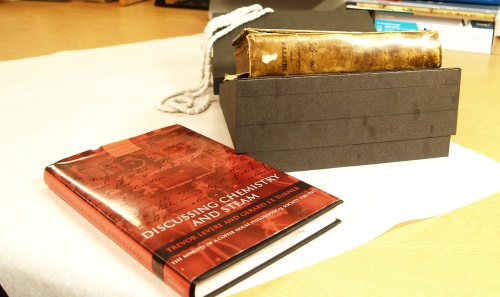

The entire set of minutes, as well as descriptions of all the members of the society, are set out in Discussing Chemistry and Steam: The Minutes of a Coffee House Philosophical Society 1780-1787, by Trevor H. Levere and Gerard L'E Turner.

Available from Oxford University Press

#5

Nicholson’s table regulator clock at the British Museum

March 3rd, 2017share this

Images copyright British Museum

The British Museum was founded in 1753, the year of William Nicholson’s birth. I have evidence of at least two of his visits to the museum. The first was as part of his research for the 1783 edition of A Critical Review of the Public Buildings, Statues, and Ornaments, in and About London and Westminster. Then in January 1790, Nicholson deposited the journals of the Count de Benyowsky with the museum for safekeeping. He might have been rather delighted to know that one of his own creations would end up there too.

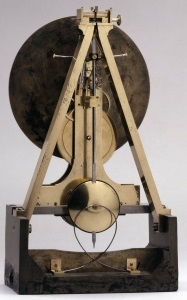

In 1958, one of Nicholson’s clocks was acquired by the British Museum as part of the Ilbert Collection - the most important collection of horology ever achieved by a private collector.

Courtenay Ilbert (1888-1956) was a civil engineer and he acquired the clock from a dealer called Clowes on 17 March 1938. He paid £20 for this 1797 regulator clock, a sum at the top end in comparison to the prices that Ilbert paid for other clocks from that period.

I recently enjoyed a visit behind the scenes with a curator of horology, Oliver Cooke, who had very kindly got the clock working for me. Previously I had seen the picture of the Nicholson’s clock on the British Museum website but had not registered the dimensions, and was surprised at how large it is.

Height: 57 centimetres

Width: 30.75 centimetres

Depth: 17.3 centimetres

The clock is described in David Thompson’s book Clocks as “an interesting example of a rather unassuming case which in reality conceals a movement of a most unusual and interesting design.”

The British Museum describes it as " SATINWOOD CASED EIGHT-DAY BRACKET TIMEPIECE WITH GRAVITY ESCAPEMENT AND CENTRE-SECONDS. Bracket timepiece; eight-day; gravity escapement; round silvered-metal dial with centre-seconds; satinwood case with moulded arched hood; glazed panels to front and sides surmounted by brass flaming vase finials. TRAIN-COUNT. Gt wheel 180" Click here for the full description.

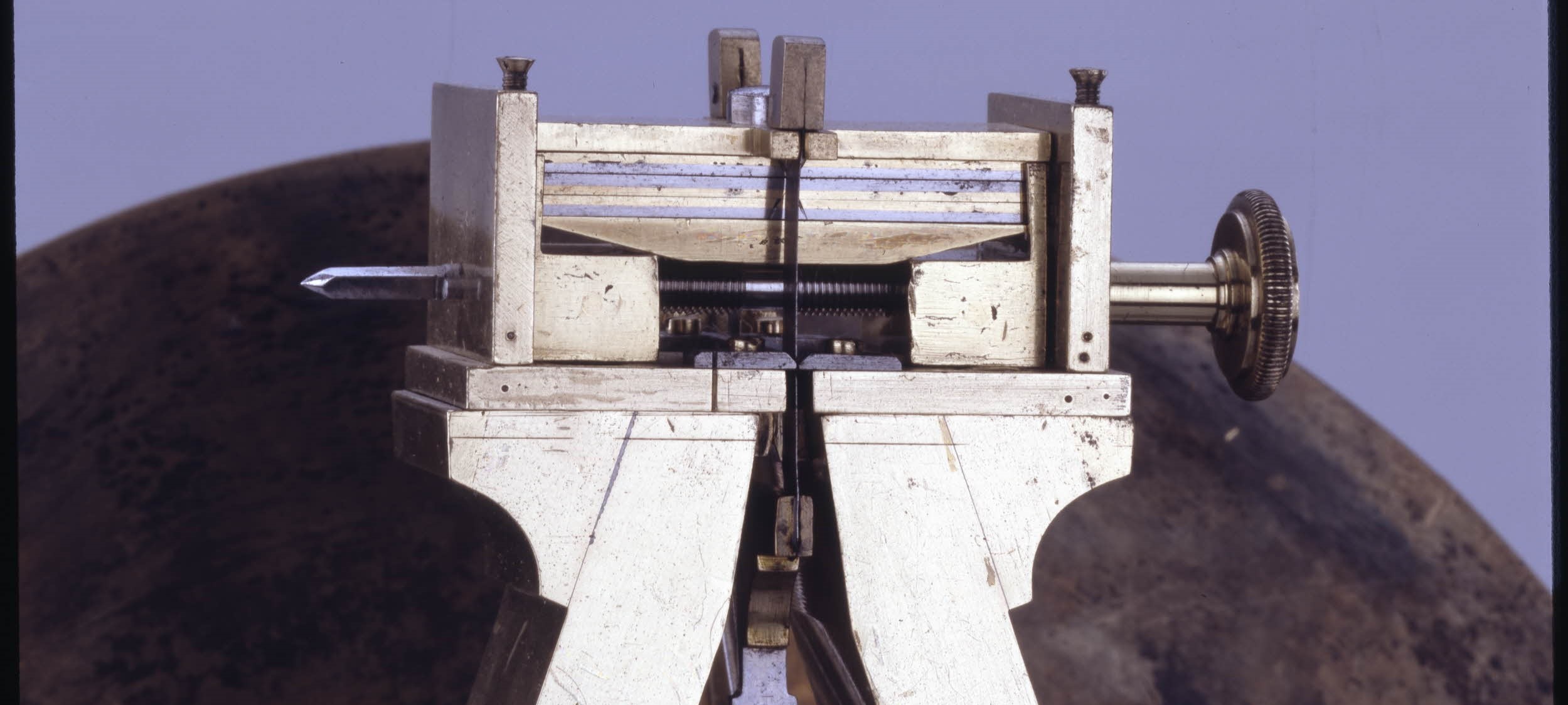

The delicate mechanism for this 8-day clock rests upon a rather unprepossessing lump of steel which acts to stabilise the clock and to support the pendulum and the movement.

The plain steel pendulum rod would expand or contract with changes in temperature, but at the top Nicholson has built an ingenious mechanism with bi-metallic strips to compensate for the changes in temperature.

“Nicholson’s big solid design is going in the right direction – and it is good to see someone outside the clock-making tradition trying something different,” said Oliver Cooke. “It was clearly an attempt to make a precision timepiece, and you can see original thinking – even if Nicholson has not got it quite right.”

Nicholson’s name is engraved on the dial where the name of the commissioner/designer would usually appear: Wm Nicholson f 1797

More information can be found in:

Clocks by David Thompson, British Museum Press, London 2004.

Precision Pendulum Clocks, The Quest for Accurate Timekeeping, by Derek Roberts, Schiffer Pub Ltd, Atglen, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 2003

#4

‘Count Rumford called but seldom’

February 10th, 2017share this

Who would be the equivalent today of the American physicist Sir Benjamin Thomson, Count Rumford, FRS (1753-1814)?

A quick review of the current fellows of the Royal Society, filtered by the scientific area of ’physics’ and a free text search for a ‘Sir’ brings up the engineer Lord Broers – an expert in nanotechnology and former Chairman of the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee.

He sounds rather important, and if he was calling round to see my father (rather than summoning my father to a meeting at his own convenience), I might think the fact was worth recording in some detail.

Frustratingly, William Nicholson’s son and biographer leaves us with nothing more than that short phrase ‘Count Rumford called but seldom’ in his memoir of his father The Life of William Nicholson (1753-1815).

There is no hint to the object of their discussions – although they might have related to Nicholson’s work on the Committee of Chemistry at the Royal Institution.

From the perspective of young William, Count Rumford was just one of many estimable visitors who worked with his father in various societies, attended Nicholson’s scientific lectures or weekly conversazione, or consulted him on patents or matters of civil engineering.

With the names of his father’s associates including the likes of Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, Richard Kirwan, Sir Joseph Banks, Humphry Davy, Frederick Accum, Richard Trevithick, Jabez Hornblower, Jean-Hyacinth Magellan and Anthony Carlisle, one can see how young William might have become blasé about one more 'important' visitor.

#3

STEM for girls - and how this biography might never have been started

February 3rd, 2017share this

Wedgwood-Museum-in-Barlaston-pic-by-Tom-Pennington-under-creative-commons

One of the questions that I am most frequently asked is how on earth I happened to be writing a book about an eighteenth-century scientist.

Colleagues tend not to be surprised that I am writing a book, as I have always written and published a great deal as part of my career in marketing. But friends and family who have known me since my school days will have witnessed a fundamental aversion to science, particularly biology (too gory) and chemistry (too smelly). I remember my science teacher as being very kind and patient, but cutting open worms and frogs and foul-stinking experiments could never capture my imagination. I hope the S in STEM is more inspiring these days.

On the other hand, history and languages had me in thrall. How could you not want to set sail with the explorers? Or imagine the thrill of inventing the steam engine or designing the first iron bridge and seeing it built? How wonderful to design an intricate piece of pottery and for it to come out of the kiln just as you had planned. I have always maintained an interest in industrial heritage and volunteered with the charity Arts & Business to help two industrial museums in the early 1990s, one of which was the Gladstone Pottery.

Luckily, my very first encounter with Nicholson was in my teens when my grandfather showed me the log book from Nicholson’s voyage to China on the Gatton in 1771. It was like having my own Marco Polo in the family.

This fact was buried deep in the recesses of my mind until around 2009 when I remembered Nicholson and his connection with Josiah Wedgwood, prompted by the Museum winning the Art Fund Prize as Museum of the Year and the financial failure of the Wedgwood business being much in the news. As this was all less than ten miles from my home, it seemed sensible to see if there might be any evidence of Nicholson’s employment by Wedgwood before the collection was dispersed – as was threatened at the time.

Sadly, I could find no employment contract or even payslips – but there was a wealth of correspondence between Nicholson and Josiah Wedgwood or his partner Thomas Bentley in regards to affairs of the agency in Amsterdam. Then later, between 1785 and 1787 Nicholson was secretary to Wedgwood at the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain (about which I will write another day).

I need to confess that it was some time before I learnt of Nicholson’s scientific works, and if my first encounter had been with anything to do with chemistry I would have backed right off.

But finding a direct connection to one of the heroes of marketing (Wedgwood is known as a father of modern marketing) and a major player in the industrial revolution - I was hooked and needed to know more.

#2

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order