Bakewell bucks the trend in independent bookshops

June 12th, 2019share this

Can there be a more perfect place for a day out than Bakewell? Not only is it in the centre of the most fabulous countryside with numerous walks and access to superb fly-fishing, but it is home to two, YES TWO! independent bookshops.

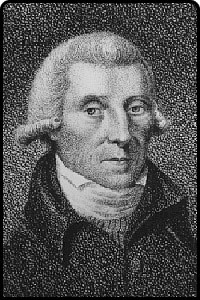

I cannot pass an antiquarian bookshop without popping in to see if they have anything by Nicholson (or Godwin or Holcroft). Invariably, the proprietor has not heard of William Nicholson (1753-1815) and thinks I mean the artist (1872 – 1949), and invariably there is nothing on the shelf for me.

But this weekend, I was thrilled to see that a new antiquarian bookshop had opened up in Bakewell and, although the owner had not heard of our hero, I was delighted to find a copy of Nicholson’s Chemical Dictionary, 3rd Edition in their scientific collection.

Hawkridge Books had a wonderful selection of books, and the shop is nicely laid out with plenty of space to move around – it is very stylish too. I have since learned that they specialise in ornithology and natural history, so it is well worth a visit.

The Bakewell Bookshop has long been a favourite pitstop after a day on the River Wye. As well as a lovely selection of books - an intelligent choice of fiction and a strong selection on local walks – it has the most welcoming coffee shop. You sit on tables within the bookshop and can borrow their Scrabble set if the weather looks too miserable to go outside. We treated ourselves to the Tea for Two – each person gets a scone, a piece of cake and a tray bake. The scones were fresh-baked that day (always the test of a good cakery), the carrot cake was ‘moistyliscious’ and the Bakewell tart was so good we had to take it home.

Both are well worth a visit.

The Enlightenment Flyfishers (first published in Flyfishers' Journal)

July 12th, 2018share this

'Angling - Preparing for Sport': published in 'British Field Sports' in 1831, this copper-engraved print depicts the kind of fishing tackle and clothing which would have been familiar to Sir Humphry Davy's literary characters Halieus, Ornither, Poietes and Physicus.

Salmononia: or Days of Fly Fishing, first published in 1809 by the Cornish chemist and inventor Humphry Davy (1778-1829), is one of the most collectable of angling books from the early nineteenth century. It was dedicated to the Irish physician and mineralogist, William Babington, a longstanding friend of Davy and a fellow founder of the Geological Society of London in 1807.

The book, written while Davy was ill, takes the form of a series of discussions between four imaginary characters: Halieus, the accomplished fly fisher; Ornither, a county gentleman who has done a little fishing; Poietes, a fly-fishing nature-lover; and Physicus a natural philosopher who has never fished.

John Davy, in his Memoirs of the Life of Humphry Davy, paints a wonderful picture of his brother on the river:

"I am sorry I have not a portrait of him in his best days in his angler’s attire. It was not unoriginal, and considerably picturesque – a white, low-crowned hat with a broad brim; its under surface green, as a protection from the sun, garnished, after a few hours’ fishing, with various flies of which trial had been made, as was usually the case; a jacket either grey or green, single-breasted, furnished with numerous large and small pockets for holding his angling gear; high boots, water-proof, for wading, or more commonly laced shoes; and breeches and gaiters, with caps to the knees made of old hat, for the purpose of defence in kneeling by the river side, when he wished to approach near without being seen by the fish; such was his attire, with rod in hand, and pannier on back, if not followed by a servant, as he commonly was, carrying the latter and a landing net."

Humphry Davy admits that Salmononia was inspired by ‘recollections of real conversations with friends’ and John’s memoir revealed that Halieus was inspired by William Babington. But whose conversations inspired the other characters?

Two friends of both Davy and Babington that must be strong contenders are William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840). They are best known for their decomposition of water into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis, achieved in 1800 with a copy of Alessandro Volta’s recently invented pile – a discovery which so excited Davy that he wrote that: ‘An immense field of investigation seems opened by this discovery: may it be pursued so as to acquaint us with some of the laws of life!’

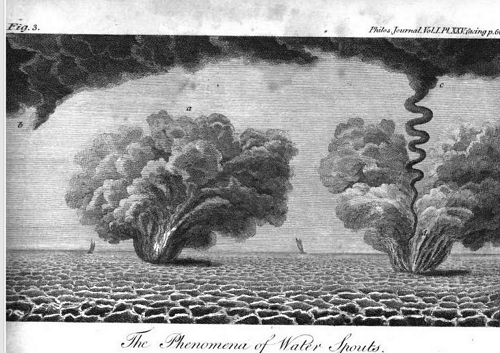

Davy met Nicholson when he arrived in London, having already corresponded and sent his first scientific papers to him in 1799 for publication in A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first monthly scientific publication in Britain, running between April 1797 and December 1813. Over the course of its life, Nicholson’s Journal included some twenty articles on fish (but not specifically fly fishing). The most important was the editor’s own in the article on the torpedo fish in 1797, which speculated about the source of the electric charge within the pelicules of the torpedo, and which inspired Volta to try the various combinations of discs (an important hint) resulting in the development of his battery pile. When Davy was appointed as Director of the Royal Institution, aCommittee for Chemical Investigation and Analysis was established, on which Nicholson was invited to participate.

Nicholson had known Babington since 1784 when they were joint secretaries of a philosophical coffee house society established by Richard Kirwan, another Irish chemist and geologist. He also knew Carlisle, then at Westminster hospital, through his close friend the radical author William Godwin whose wife Mary Wollstonecraft was attended by the surgeon before she died in 1797.

Unfortunately, we don’t have an account of Davy, Babington, Carlisle and Nicholson fishing together, but it is a scene that we might easily imagine.

Nicholson, who was a prolific publisher, in his 1809 British Encyclopedia, or Dictionary of Arts and Sciencesdescribes fly fishing as ‘an art of so much nicety, that to give any just idea of it, we must devote an article to it.’ Sadly, he does not write about fly-fishing as eloquently as he does about chemistry, simply describing a number of flies and his only advice on how to fish is ‘keep as far from the water’s edge as may be, and fish down the stream with the sun at your back, the line must not touch the water.’

But, in a memoir of The Life of William Nicholson, the manuscript of which has finally been published 150 years after it was written, there is a charming account by Nicholson’s son of fishing trips with Carlisle in around 1803:

"Carlisle was at that time about thirty years of age, good looking and active …

Having passed his early days at Durham and in Yorkshire, Carlisle was fond of the country and country sports. We had many a day’s fishing at Carshalton, where his intimacy with the Reynolds and Shipleys procured him the use of part of the stream where the public were excluded. He was a skilful fly fisher and during the day I generally carried the pannier and landing net, but towards night when the mills stopped, and the water ran over a bye-wash, I with my bag of worms and rod managed to hook some fish as big as were taken during the day.

We also had fishing grounds at a place in Hertford called Chenis which was rented as I understood by Carlisle and a fellow sportsman called Mainwaring. These two gentlemen and myself as a third in a post-chaise used to start at 6.00 o’clock am, breakfast at Ware or Hoddesdon and forward to the fishing, which was fine for a boy of fourteen. And then Mr Mainwaring always took a fowling piece with him and occasionally shot a bird which was worth all the fish, rods and lines and all.

Chenis was a remarkably quiet rural place and the little inn we slept at was situated in a settlement of some half dozen cottages and houses, but what its name was I do not know. On one occasion when our companion was called away Carlisle and I remained there for a day or two. We were very successful in our fishing and were about to depart when it turned out there was a county election going forward and there was no conveyance to be had for love or money. Carlisle was wanted at home and we had no choice but to start on foot, so away we went after breakfast with a boy to show us a footpath way through fields to Rickmansworth where we hoped to get some conveyance to London.

Carlisle had the best share of the luggage and the boy and I the remainder. The country we travelled was beautifully undulated and of a dry sandy soil. It was very hot and I suspect I was the first to feel fatigue. After a long trudge we stopped at a gate leading into a sandy lane and looking back at the hillside I was amazed at the display of poppies in full bloom, the whole field was a mass of crimson, a new sight to me.

I was very thirsty and tired and have often thought of that field and Burns’ immortal lines:

Pleasures are like poppies spread;

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

or like the snow fall on the river.

a moment white then melts forever.[1]

But time, like a pitiless master, cried onward and we had to trudge again. At last our guide left us on the dusty high road to Rickmansworth, where in time we arrived. Here we got some refreshment and awaited til a return post-chaise conveyed us to London. We had walked nearly 30 miles and it was my first walking adventure of any magnitude."

The story was written when young Nicholson was eighty, and his geography seems a bit muddled – I have been unable to locate a place called Chenis, in Hertford – but records exist for one in Buckinghamshire in the 1770s. Could he mean the river Chess if he was near Ware and Hoddesdon? The Chess also passes near a village called Chenies just a few miles from Rickmansworth. (If any readers of the Flyfishers’ Journal can help, I would be very interested to hear from them.)

Carlisle went on to enjoy a stellar medical career, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1804, where he became Professor of Anatomy 1808 to 1824.

In 1809, he published an account of some experiments into how fish swam, by cutting various fins off seven fish each of dace (cyprinus leusiscus), roach (cyprinus rutilus), gudgeon (cyprinus gobio) and minnow (cyprinus phoxinus). He recorded how, on removal of the pectoral fin [2] its progressive motion was not at all impeded, but it was difficult for the fish to ascend; on removing the abdominal fin as well, the fish could not ascend; on removing the single fins, ‘produced an evident tendency to turn around, and the pectoral fins were kept constantly extended to obviate that motion; … and so on, until all fins had been removed from the seventh fish which cruelly ‘remained almost without motion’.

Carlisle was appointed Surgeon Extraordinary in 1820 to King George IV and was knighted in 1821. He died in 1840, never losing his love of fishing.

"Sir Anthony Carlisle had been called into the Prince Regent mainly to consult as to what wine he should drink. Having ascertained that brown sherry was the favourite of the day, he recommended it and gave great satisfaction.

Carlisle wrote to me, while I was engaged in a survey in Yorkshire, to find him a handy honest unsophisticated lad as a servant. I did my best and sent him one. The lad turned out a stupid dog, but when I visited London a short time afterwards and dined with Carlisle this boy waited and amused me by incessantly answering Carlisle ‘Yes Sir Anthony, … no Sir Anthony’ and ‘Sir Anthony’ at the beginning, middle and end of every sentence. All this passed as a matter of course and reminded me how calmly we bear our dignities when they fall upon us.

Carlisle was a true fisherman and a great admirer of honest Izaak Walton and used to quote from that delightful book The Compleat Angler, so that when any food or wine was better than common he said ‘it was only fit for anglers or very honest men’; and then he had another joke when we got thoroughly wet on our fishing excursions, saying ‘it was a discovery, how to wash your feet without taking off your stockings’."

#24

[1] From Robert Burns, ‘Tam o’ Shanter’, Edinburgh Magazine, Mar 1791.

[2] All these articles can be found by searching the index.

In print at last after 150 years: 'The Life of William Nicholson, by his Son'

February 24th, 2018share this

I was extremely fortunate in having been signed by one of the leading independent publishers - Peter Owen Publishing. This was the first publisher that Iapproached (so very fortunate indeed) and is surely testament to the importance of Mr Nicholson, rather than my own humble credentials.

As the main biography is taking much longer than anticipated (see below), we decided to publish The Life of William Nicholson by his Son as a prelude - exactly 150 years after it was written in 1868. This rare manuscript has been held by the Bodleian Library since 1978.

In addition to the edited text of The Life of William Nicholson by his Son, the book also includes:

- a timeline of Nicholson's life, work and inventions;

- details of Nicholson's published works;

- Nicholson's patents and inventions;

- Nicholson's list of members of the coffee house philosophical society of the 1780s (not as complete as in Discussing Chemistry and Steam by Levere and Turner …, but indicative of Nicholson's associates at the time); and

- committee Members of the Society for Naval Architecture of 1791.

Design agency Exesios have done a super job of the cover, and there is a special treat on the inside with:

- a map of all Nicholson's known homes on (Drew's map of 1785); and

- the drawings from the 1790 cylindrical printing patent.

I'm delighted that Professor Frank James of UCL and the Royal Institution has written an afterword which focuses on Nicholson's scientific contributions. Considering his literary associates, Professor James also suggests why Nicholson was never made a member of the Royal Society, despite his many achievements.

The modern biography of William Nicholson (1753-1815)

With 110,000 words under my belt, I was beginning to think that the end was in sight on the modern biography - until I met up with Hugh Torrens, Emeritus Professor of History of Science and Technology at University of Keele, to chat about some of the civil engineering issues.

Our first meeting resulted in a very exciting list of 29 items of further research which will keep me busy researching and writing for several months.

Meanwhile, you can keep up to date with news and developments here on the blog.

#22

Publication update: Is this the closest I will get to appearing alongside Liam Neeson?

December 17th, 2017share this

OK, that got the ladies’ attention …!

I have been so busy checking facts, dates and references that, with my brain firmly in the eighteenth century, I forgot to update the website with our publication plans.

Firstly, I am delighted to say that I was signed up by PeterOwen Publishers, one of the leading independents. I was the last non-fiction writer to besigned before Peter Owen passed away at the grand age of 89. He established his publishing house in 1951 and accumulated a record-breaking ten Nobel prize-winners over sixty-five years in business.

Miraculously, they were the first publishing house that I approached but, like those of you who know Nicholson already, they instantly recognised that our hero was in need of a biography.

In Peter Owen’s obituary in the Telegraph, he was described as ‘bewilderingly eclectic’ and a ‘champion of the obscure’ – given that Nicholson and I are little known (for now), that seems like a pretty good fit. I shall enjoy being obscure in good company.

The Life of William Nicholson was written 150 years ago and until now, has been available only to historians via a visit to the Bodleian Museum (MSS. Don. d. 175, e. 125), but it is now available to order online and will be in shops in the new year.

So, what has this got to do with Liam Neeson? Well I couldn’t help being just a little thrilled to see his brooding presence either side of Mr Nicholson on the cover of Nobel prizewinner Silence by Shusaku Endo (a recent film by Martin Scorsese).

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

Just don’t mention that there isn’t a movie (yet)!

#18

If museum image fees are "killing art history” what hope for historians of science and commerce …

November 11th, 2017share this

Image Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay

Well done to the group of art historians who wrote to The Times on 6 November:

“The fees charged by the UK’s national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished. Such fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge that is the very purpose of public museums and galleries. Fees charged for academic use pose a serious threat to art history: a single lecture can cost hundreds of pounds; a book, thousands.”

A full copy of the letter (and more recent developments) can be found on the website www.arthistorynews.com.

As someone who uses images as a daily basis for marketing, I am used to being able to licence stock images (photographs or drawings) from websites such as Istockphoto or Shutterstock for a reasonable fee, and was shocked to find out how much some museums wished to charge, how complicated the fee structure can be, and how inconsistent the pricing structure is across various national institutions.

Initially, I had been keen to include a large number of illustrations in my modern biography of Nicholson - hoping to bring some potentially dry scientific subjects to life - but I soon had to modify my aspirations.

By way of example, when writing this blog on Nicholson’s clock, which is in the British Museum but not on public display, I was only allowed to include the three images provided by the Museum under the Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence, “an internationally recognised licence recommended by one of the Directives we are expected to follow as a public sector body.”

However, the museum did not have photographs of some interesting and unique aspects of the clock including a close up of the inscription “William Nicholson / 1797” and a side view showing the fusee mechanism.

While I was permitted to take photographs, and video, for my personal use during the visit – I was not allowed to use these on the blog, as

“… you can certainly use your own images for ‘private and non-commercial purposes’ but I’m afraid you are not permitted to publish these images.

This allows us to maintain the quality of representation of our objects, keep a record of what is used and avoid any complications regarding future copyright.

The Museum’s Visitor Regulations regarding personal photography is:

8. Film, photography and audio recording

8.1 Except where indicated by notices, you are permitted to use hand-held cameras (including mobile phones) with flash bulbs or flash units, and audio and film recording equipment not requiring a stand. You may use your photographs, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/2011-11-14%20Visitor%20Regulations%20FINAL.pdf

The image rights team kindly offered to “easily arrange new photography for £85 + VAT (30 day turnaround but often much faster)”. How they might incur such costs was a mystery to me, and I did not bother to ask whether this was per photograph.

This seems to go against the British Museum’s object of:

The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be FREELY accessible.

Given that Nicholson’s clock is not on public display, one might have thought they would see the benefit of some broader exposure online – at no cost to the public purse.

In thinking about what to include in book, I am faced with this pricing structure for scholarly and academic books:

Total combined print run and download units (prices per image ex-VAT):

Up to 500: £30

501 – 1,000: £40

1,001 – 2,000: £50

2,001 – 3,000: £60

My initial plan to include up to eight images, in order to properly detail the design and mechanics, would set me back £400 if the print run is between 1,000 and 2,000. Somehow, I doubt that Neil MacGregor has this problem when choosing his next set of 100 hundred objects.

There is a big difference between the commercial value in the photograph of Nicholson’s clock’s fusee and an iconic sculpture such as the Discobolus, of which the British Museum sells replicas for £2,500.

I should think that the trustees of the British Museum would have a better understanding than most of the fact that many niche historical books have only a limited customer base, but are nonetheless extremely valuable in terms of the spread of knowledge and understanding.

#17

Book Review – A walk on part in ‘The Shape of Water’

October 22nd, 2017share this

As the marketing guru John Hegarty said (and I am fond of quoting) “Do interesting things, and interesting things will happen to you” – and how true this has been. Little did I know where my first visit to the Wedgwood Museum would lead … to Tasmania.

William and Catherine Nicholson’s daughter Mary (1787 - 1807/8) married a Captain with the East India Company, Hugh Macintosh (1775 - 1834) at Fort St George, in Madras, India. Sadly, she died very shortly after giving birth to William Hugh Mackintosh (1807-1840) in December 1807.

Hugh Macintosh eventually travelled to Van Diemen‘s Land (now Tasmania) where, in partnership with Peter Degraves, he was one of the founders of The Cascade Brewery Company in 1824.

Back in the summer 2016, I received an email from the author Anne Blythe Cooper in Tasmania in regard to this connection. As it was the middle of the day, and the time difference seemed favourable, I decided to give her a ring – only to find that she was in Yorkshire.

The subject of interest for Anne was Sophia (the wife of Peter Degraves), about whom little was known. Like the women in Nicholson’s life, and many at that time, so little was recording in writing that they are almost invisible today.

Anne was also planning a trip to Anglesey, which meant that she would be almost passing Staffordshire. Seizing the opportunity, we arranged to meet and spent many hours trying to fill plug holes in the histories of the Degraves and Macintosh/Nicholson family connections.

In The Shape of Water: Imagined fragments from an elusive life: Sophia Degraves of Van Diemen's Land, a work of historical fiction, Anne Blythe-Cooper tells the fascinating story of the life, hardships, imprisonments and eventual success of the Degraves family through the eyes of Sophia.

Knowing very little of the history of the Van Diemen's Land, renamed as Tasmania in 1856, I found it a fascinating read. The descriptions of the societal, entrepreneurial and environmental conditions are very vivid, and it was delightful to read William and Mary Nicholson’s first appearances in a work of historic fiction (as far as I am aware).

I was interested to learn of the Tasmanian tiger (sadly declared extinct in 1936) and Mount Wellington, the development of the brewery and the theatre. Peter Degraves, sounds like a nightmare of a husband – but that certainly makes the book an enjoyable read.

So far it is only available via Forty South Publishing in Tasmania, but as the early story is set in London and many of the characters have English heritage – it deserves to be published in the UK too.

For now, it can be ordered via via Forty South Publishing - The Shape of Water by Anne Blythe-Cooper.

#16

STEM for girls - and how this biography might never have been started

February 3rd, 2017share this

Wedgwood-Museum-in-Barlaston-pic-by-Tom-Pennington-under-creative-commons

One of the questions that I am most frequently asked is how on earth I happened to be writing a book about an eighteenth-century scientist.

Colleagues tend not to be surprised that I am writing a book, as I have always written and published a great deal as part of my career in marketing. But friends and family who have known me since my school days will have witnessed a fundamental aversion to science, particularly biology (too gory) and chemistry (too smelly). I remember my science teacher as being very kind and patient, but cutting open worms and frogs and foul-stinking experiments could never capture my imagination. I hope the S in STEM is more inspiring these days.

On the other hand, history and languages had me in thrall. How could you not want to set sail with the explorers? Or imagine the thrill of inventing the steam engine or designing the first iron bridge and seeing it built? How wonderful to design an intricate piece of pottery and for it to come out of the kiln just as you had planned. I have always maintained an interest in industrial heritage and volunteered with the charity Arts & Business to help two industrial museums in the early 1990s, one of which was the Gladstone Pottery.

Luckily, my very first encounter with Nicholson was in my teens when my grandfather showed me the log book from Nicholson’s voyage to China on the Gatton in 1771. It was like having my own Marco Polo in the family.

This fact was buried deep in the recesses of my mind until around 2009 when I remembered Nicholson and his connection with Josiah Wedgwood, prompted by the Museum winning the Art Fund Prize as Museum of the Year and the financial failure of the Wedgwood business being much in the news. As this was all less than ten miles from my home, it seemed sensible to see if there might be any evidence of Nicholson’s employment by Wedgwood before the collection was dispersed – as was threatened at the time.

Sadly, I could find no employment contract or even payslips – but there was a wealth of correspondence between Nicholson and Josiah Wedgwood or his partner Thomas Bentley in regards to affairs of the agency in Amsterdam. Then later, between 1785 and 1787 Nicholson was secretary to Wedgwood at the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain (about which I will write another day).

I need to confess that it was some time before I learnt of Nicholson’s scientific works, and if my first encounter had been with anything to do with chemistry I would have backed right off.

But finding a direct connection to one of the heroes of marketing (Wedgwood is known as a father of modern marketing) and a major player in the industrial revolution - I was hooked and needed to know more.

#2

Next steps ...

December 14th, 2016share this

Photograph from personal collection

At last, 110,000 words (excluding index and bibliography) describing the life of William Nicholson are off my desk and in the capable hands of the publishers. It only remains for me to finalise the list of images and obtain all the copyright permissions.

Meanwhile, I am not quite ready to consign a decade’s research to the archives. A pile of 'out-takes' and stories that were tangential to the life of William Nicholson beg me not to neglect them. On my PC is a document entitled 'things to do after the book' which is like a bucket list of historical adventures for me to pursue.

In this blog, I plan to flesh out some of the background to Nicholson's life from 1753 to 1815 and get better acquainted with his numerous friends and colleagues. I’ll share links to useful resources related to the Enlightenment, and I hope that some of the real experts on the period might be persuaded to contribute some articles on Nicholson's scientific achievements.

I will also try and record some of my experiences along the way, and most of all, I hope that this might inspire other historians to discover, examine and share more information about Nicholson and his work.

Nicholson published his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts over seventeen years from April 1797 to December 1813. I’m not sure if this 21st Century edition will be able to match this, but here we go …

#1

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal 334,822

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order