Eighteenth Century Mr Nicholson launches his YouTube Channel

December 15th, 2020share this

When William Nicholson launched his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts in 1979, part of his motivation was to speed up the transfer of scientific knowledge.

If he lived today, he would surely have embraced social media for that purpose - never lowering himself to insults or trolling!

Now he has added a Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account to his media channels, and we are able to share excerpts from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ a performance for the Bloomsbury Festival 2020 which took place in the open air of St George’s Gardens, London where Nicholson is buried.

Directed and introduced by Ian Brown, episode one is the historical part where his biographer Sue Durrell interviews Nicholson who has returned from his grave in the gardens to talk about his life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nicholson is brought to life most ably by actor Julian Date, who reminisces about his life at the crossroads of Georgian arts, literature, science, and commerce, and discusses the importance of his discovery in splitting water using Volta’s battery, alongside his friend Dr. Carlisle.

The short three excerpts in this video cover:

• Working for Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam and at the General Chamber of Manufacturers

• Nicholson’s motivation for launching his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts; and

• Remembering Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution and recalling the experiment with Anthony Carlisle where they split water into hydrogen and oxygen in May 1800.

This is the first of two videos from this event. Part two shows demonstrations of the experiment and discusses its implications in the quest for clean energy.

Julian Date is represented by Hilary Gagan Associates.

#36

Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture and the feminists’ new clothes

November 15th, 2020share this

I guess I feel that I have a very small right to claim a connection to Mary Wollstonecraft, as my 5 x great grandmother Catherine Nicholson was one of the two close friends (along with Eliza Fenwick) who stayed with and comforted Mary Wollstonecraft in her dying days.

Catherine wrote to William Godwin after his wife’s death to say:

Myself and Mrs Fenwick were the only two female friends that were with Mrs Godwin during her last illness. Mrs Fenwick attended her from the beginning of her confinement with scarcely any interruption. I was with her for the four last days of her life …

She was all kindness and attention & cheerfully complied with everything that was recommended to her by her friends. In many instances she employed her mind with more sagacity upon the subject of her illness than any of the persons about her …

I noticed the fundraising appeal for the statue in 2019 – but it was not clear how much they were trying to raise; how much was still needed; and how it would be spent. There was no information about the finances on the website, only the vague statement “A capital sum for the memorial and a revenue source for the Society will ensure that Wollstonecraft’s legacy and learning will continue.” I was simply seeking to clarify the financial position, but my polite enquiry elicited a rather frosty response, suggesting that I should find another memorial to support.

I’m a fan of figurative sculptures and am lucky enough to live near to the National Memorial Arboretum. As you walk round, you cannot fail to be moved by the way that the sculptures make a historic figure lifeisize (or larger) making more real the boy who represents all those shot at dawn, thechild evacuees, or the ladies Women’s Land Army and Timber Corps. I’d never heard of lumber jills before, but seeing the memorial prompted me to find out more.

So, OK I’ll admit that I’m not very radical in my taste for sculptures, And Mary Wollstonecraft was a radical, so she needs a radical sculpture – right?

Mary Wollstonecraft was strong and adventurous, working as a journalist she headed off to Paris to cover the revolutionary troubles for the publisher Joseph Johnson. But, I’m afraid I cannot see strength and courage in this sculpture.

She was a thinker, an author, and an educator. How is this portrayed in the sculpture? And how is it meant to inspire young women toexpand their minds?

The Mary on the Green website states that “Her presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people in Islington, Haringey and Hackney” … and The Wollstonecraft Society’s objectives are “to promote the recognition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s contribution to equality, diversity and human rights.”

In Original Stories from Real Life: With Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (1788), Wollstonecarft wrote of a woman who lost her good looks to the small pox and “.. as she improved her mind, she discovered that virtue, internal beauty,was valuable on its own account, and not like that of the person, which resembles a toy, that pleases the observer, but does not render the possessor happy.”

I’m struggling to see how any child who sees this toy-like sculpture will come away with the message that cultivating the mind is more valuable than looks.

On the other hand, (having once accompanied a group of 11-year olds on a school trip to Paris) it is not hard to imagine the giggling and sexist comments that might emerge among some and the embarrassment that might be felt by others.

I don’t envy the teacher who has to create a lesson plan around this educational trip!

#34

Thomas Holcroft – Landlord and long-time friend (part 1)

May 9th, 2018share this

Towards the end of the 1770s, after returning to London from his work for Wedgwood in Amsterdam, William Nicholson took lodgings with the writer Thomas Holcroft and was introduced to his landlord’s colourful circle of friends. A fellow lodger was Elizabeth Kemble whose father had established a strolling theatre company, and whose sister Sarah Siddons was a well-known actress.

From their rooms in Southampton Buildings at the top of London’s Chancery Lane, Holcroft and Nicholson often headed down to ‘Porridge Island’ a small row of cook-shops near to St Martins-in-the-Field where they enjoyed a nine-penny dinner and met up with other writers and musicians.

According to his son, Nicholson wrote a great deal for Holcroft who was used to having an amanuensis. The first piece of work to which Nicholson is know to have contributed was a novel published in 1780 entitled Alwyn: or The Gentleman Comedian. William Hazlitt, who completed Holcroft’s memoir (with assistance from Nicholson) explained how ‘it was originally intended that N.... should compile from materials to be furnished by Holcroft, but of which he in fact only wrote a few short letters, evidently very much against the grain.’

The second piece of work, which was attributed to Nicholson, was the prologue to a drama called Duplicity. The play opened in October 1781 at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, and the prologue was performed by Mr Lee-Lewes.

The opening performance was met with great applause and positive reviews. Holcroft described his feelings as ‘having escaped from the Dog of Hell, the Elysian fields are before me, if I have but taste and prudence to select the sweets.’ One can imagine the celebrations in Southampton Buildings that night and the excitement of Nicholson and his new bride as they mingled with the cast which included Elizabeth Inchbald, another renowned actress.

Unfortunately, within just a few days, Duplicity failed to generate enough revenue to cover the expenses of the house and Mr Harris of the Theatre Royal declared that ‘unless it was commanded by the King, he should not think of playing it any more’.

Nicholson’s son claimed that his father continued to produce ‘essays, poems and light literature for the periodicals of the day’ while working with Holcroft, but frustratingly for us ‘to none of which he put his name’.

A couple of years later, after war with France had ended, Holcroft made his name with the unscrupulous infringement of another playwright’s intellectual property. Having travelled to Paris to see The Marriage of Figaro by Beaumarchais, Holcroft had requested a copy of the script but was refused. So, over ten nights in September 1784, he and a friend attended the performance and recorded the entire script. In December that same year, with no respect for creative copyright, Holcroft took to the stage at Covent Garden in the role of Figaro for its first performance in Britain.

A decade later in 1792, Holcroft produced his best-known play The Road to Ruin. Let us leave Holcroft to bask in his glory for a little while, and I will return to his life after 1792 in due course.

#23

Publication update: Is this the closest I will get to appearing alongside Liam Neeson?

December 17th, 2017share this

OK, that got the ladies’ attention …!

I have been so busy checking facts, dates and references that, with my brain firmly in the eighteenth century, I forgot to update the website with our publication plans.

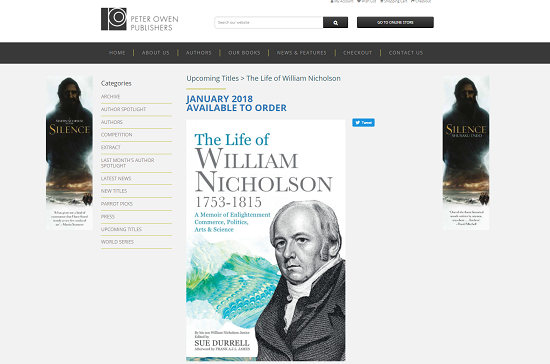

Firstly, I am delighted to say that I was signed up by PeterOwen Publishers, one of the leading independents. I was the last non-fiction writer to besigned before Peter Owen passed away at the grand age of 89. He established his publishing house in 1951 and accumulated a record-breaking ten Nobel prize-winners over sixty-five years in business.

Miraculously, they were the first publishing house that I approached but, like those of you who know Nicholson already, they instantly recognised that our hero was in need of a biography.

In Peter Owen’s obituary in the Telegraph, he was described as ‘bewilderingly eclectic’ and a ‘champion of the obscure’ – given that Nicholson and I are little known (for now), that seems like a pretty good fit. I shall enjoy being obscure in good company.

The Life of William Nicholson was written 150 years ago and until now, has been available only to historians via a visit to the Bodleian Museum (MSS. Don. d. 175, e. 125), but it is now available to order online and will be in shops in the new year.

So, what has this got to do with Liam Neeson? Well I couldn’t help being just a little thrilled to see his brooding presence either side of Mr Nicholson on the cover of Nobel prizewinner Silence by Shusaku Endo (a recent film by Martin Scorsese).

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

Just don’t mention that there isn’t a movie (yet)!

#18

If museum image fees are "killing art history” what hope for historians of science and commerce …

November 11th, 2017share this

Image Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay

Well done to the group of art historians who wrote to The Times on 6 November:

“The fees charged by the UK’s national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished. Such fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge that is the very purpose of public museums and galleries. Fees charged for academic use pose a serious threat to art history: a single lecture can cost hundreds of pounds; a book, thousands.”

A full copy of the letter (and more recent developments) can be found on the website www.arthistorynews.com.

As someone who uses images as a daily basis for marketing, I am used to being able to licence stock images (photographs or drawings) from websites such as Istockphoto or Shutterstock for a reasonable fee, and was shocked to find out how much some museums wished to charge, how complicated the fee structure can be, and how inconsistent the pricing structure is across various national institutions.

Initially, I had been keen to include a large number of illustrations in my modern biography of Nicholson - hoping to bring some potentially dry scientific subjects to life - but I soon had to modify my aspirations.

By way of example, when writing this blog on Nicholson’s clock, which is in the British Museum but not on public display, I was only allowed to include the three images provided by the Museum under the Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence, “an internationally recognised licence recommended by one of the Directives we are expected to follow as a public sector body.”

However, the museum did not have photographs of some interesting and unique aspects of the clock including a close up of the inscription “William Nicholson / 1797” and a side view showing the fusee mechanism.

While I was permitted to take photographs, and video, for my personal use during the visit – I was not allowed to use these on the blog, as

“… you can certainly use your own images for ‘private and non-commercial purposes’ but I’m afraid you are not permitted to publish these images.

This allows us to maintain the quality of representation of our objects, keep a record of what is used and avoid any complications regarding future copyright.

The Museum’s Visitor Regulations regarding personal photography is:

8. Film, photography and audio recording

8.1 Except where indicated by notices, you are permitted to use hand-held cameras (including mobile phones) with flash bulbs or flash units, and audio and film recording equipment not requiring a stand. You may use your photographs, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/2011-11-14%20Visitor%20Regulations%20FINAL.pdf

The image rights team kindly offered to “easily arrange new photography for £85 + VAT (30 day turnaround but often much faster)”. How they might incur such costs was a mystery to me, and I did not bother to ask whether this was per photograph.

This seems to go against the British Museum’s object of:

The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be FREELY accessible.

Given that Nicholson’s clock is not on public display, one might have thought they would see the benefit of some broader exposure online – at no cost to the public purse.

In thinking about what to include in book, I am faced with this pricing structure for scholarly and academic books:

Total combined print run and download units (prices per image ex-VAT):

Up to 500: £30

501 – 1,000: £40

1,001 – 2,000: £50

2,001 – 3,000: £60

My initial plan to include up to eight images, in order to properly detail the design and mechanics, would set me back £400 if the print run is between 1,000 and 2,000. Somehow, I doubt that Neil MacGregor has this problem when choosing his next set of 100 hundred objects.

There is a big difference between the commercial value in the photograph of Nicholson’s clock’s fusee and an iconic sculpture such as the Discobolus, of which the British Museum sells replicas for £2,500.

I should think that the trustees of the British Museum would have a better understanding than most of the fact that many niche historical books have only a limited customer base, but are nonetheless extremely valuable in terms of the spread of knowledge and understanding.

#17

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal 329,999

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order