Who invested in the Portsmouth and Portsea Waterworks in 1809?

April 10th, 2025share this

Who were the people that invested in William Nicholson's project to supply water to the residents of Portsmouth and Portsea in 1809?

- Allen, Ann

- Allen, Herbert

- Archer, Sarah

- Arnaud, Elias

- Arnaud, Elias Bruce

- Atherley, Arthur

- Atwood, Henry

- Bacchus, William

- Baker, Nathaniel

- Baker, William & Sons

- Baker, William Jnr

- Bonham, Thomas*

- Bartlett, William

- Barton, Charles

- Bedford, Mrs

- Belam, Thomas

- Bell, John

- Binstead, John

- Bird, J Y

- Boyes, Thomas

- Thomas Bonham (Director of Pikes?)

- Brine Edward

- Brown, William

- Burbey, Richard

- Burbey, Richard Jnr

- Burridge, William

- Busher, John

- Bussell, Rev John Garrett

- Bussell, Rev William Marchant

- Callaway, George Augustus

- Callaway, Roger

- Casher, Edward

- Carter, James H

- Carter, William Grover

- Cave, Joseph

- Cave, Joseph Jnr

- Clarke, Andrew

- Clarke, Joseph

- Clay, James

- Clay, William

- Collins, John

- Cook John

- Corsbic, Joseph

- Cousins, John

- Cuthbert, Rev George

- Deacon, James

- Deacon, Mrs Sarah

- Deacon, William

- Draper, John Jnr

- Draper, John Sr

- Edgecombe, Thomas

- Elland, Thomas

- Fauntleroy, Henry

- Fielding, George

- Fielding, Sarah

- Flaxman, Thomas Charles

- Fowler, James

- Fry, Henry

- Gain, William Jr

- Garrett, George

- Garrett, William

- Gibbins, William

- Gittons, Edward

- Godwin, John

- Goldfinch, John

- Goldfinch, William

- Goldson, William

- Goodenough, George Trenchard

- Goodeve, Edward

- Goodeve, James

- Grant, George

- Grant, Thomas

- Grant, William

- Grey, Robert

- Grossmith, William

- Hammond, William

- Harris, William

- Hawkins, Stephen

- Heath, Matthew

- Heather, Moses

- Heather, Thomas

- Hector, Charles John

- Hickley, John Allen

- Hill, Samuel Jnr

- Hinton, Benjamin

- Hodder, William

- Holland, John

- Hollingsworth, Elizabeth

- Hollingsworth, James

- Horsey, James

- Howard, Daniel

- Hunt, Edward

- Innes, James

- Lathem, Trevers Hull

- Lazarus, Lewis

- Leese, John Smith

- Lenaker, James

- Levi, Jacob

- Lind, John

- Lindegren, Andrew

- Lindegren, John

- Lipscombe, Kempfler

- Lipscombe, Kempfler Jnr

- Mariner, Thomas

- Marsh, William

- Matthews, William

- Meik, Thomas

- Merrit, Thomas Turner

- Miall, Moses

- Mills, Samuel

- Minchin, Thomas Andrew

- Moors, James

- Moses, Abraham

- Mottley, James Charles

- Mottley, Thomas

- Moyle, John

- Nathan, Jacob

- Nathan, Phillip

- Neal, George

- Nicholson, William

- Nicholson, Wm Jr

- Oswald, Alexander

- Owen John

- Owen, Jacob

- Padwick, William

- Palmer, Ann

- Palmer, Hester

- Parke, Edward

- Passard, Thomas

- Passard, Thomas Jnr

- William Pike (Pike & Co – Directors may be listed separately*)

- Pinhorn, James

- Poulden, Alexander

- Pratt, Thomas

- Pushmann, Joseph

- Pye, Thomas Robert

- Pye, William

- Pye, William Jnr

- Rands, James

- Read, James

- Read, John

- Rood, John

- Read, Robert

- Read, William Price

- Richards, James

- Robinson, Mark (Admiral)

- Roote, Thomas

- Rouse, Thomas Burley

- Seeds, Thomas

- Serjeant, William

- Sharp ,Thomas

- Sharp, Francis

- Sharp, Thomas Tresbar

- Shepheard, William

- Sheppard, Thomas

- Shugar, John Sutton

- Sloper, Robert Stokes

- Smith & Robinson:

- Smith, John

- Robinson, James Newton

- Smith, Lawrence

- Smith, Robert

- Smithers, John

- Smithers, Joseph

- Snook, John

- Snook, John Jr

- Snook, Matthew

- Spearing, J. E.

- Stebbing, George

- Stephens, John Mortimer

- Stevens, Ruth

- Stewart, H’ble Montgomerie

- Stewart, John Henry

- Stracey, Josias Henry

- Stroud, Robert

- Stroud, William

- Taber, Charles &

- Taber, Charles Jnr

- Tollervey, Edward

- Temple, Richard Godman

- Tomkins, Gregory

- Turner, George

- Turner, Joseph Kelner

- Turner, William*

- Walcot, Thomas

- Wallis, William Parry

- Welch, George

- Wills, Thomas

- Westmore, John

- White, Henry

- White, Richard

- Whitebread, William

- Whitwood. Thomas Jnr

- Williams, John

- Williams, John

- Withers, John

- Woodward, William

- Zachariah, Levi

- Zachariah, Jacob

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

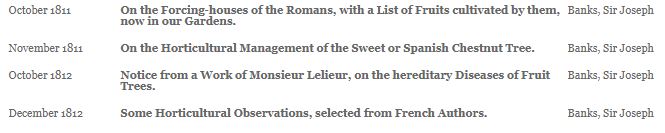

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

Change time at the Royal Exchange

September 27th, 2017share this

Image: The Royal Exchange, London c1750, Courtesy of Wikigallery

The following sentence in The life of William Nicholson by his Son caused me to Google ‘Change Time’ to see what this referred to:

‘And daily congregated in the shop after change time six or eight or more of the leading merchants to gossip over politics and the affairs of the day …’

Rather amusingly, an explanation came up from our very own Mr Nicholson in The British Encyclopedia, 6 vols of 1809, which I thought worthy of sharing due to the severity of the punishments threatened:

In 1703, the following notice appeared in the public papers: "An act of the Lord Mayor and Court of Alder men is affixed at the Exchange, and other places in this City, by which all persons are prohibited coming upon the Royal Exchange to do business before the hours of twelve o'clock, and after the hour of two, till evening change: Wherein it is further enacted, that for a quarter of an hour before twelve the Exchange bell shall ring, as a signal of change time ; and shall also begin to ring a quarter of an hour before two, at which time the change shall end : and all persons shall quit it, upon pain of being prosecuted to the utmost, according to law. That the gates shall then be shut up, and continue so till evening change time; which shall be from the hours of six to eight from Lady-day till Michaelmas, and from Michaelmas to Lady-day from the hours of four to six; before and after which hours the bell shall ring as above said. And it is further enacted, that no persons shall assemble in companies, as stock jobbers, &c. either in Exchange Alley, or places adjacent, to stop up and hinder the passage from and to the respective houses thereabouts, under pain of being immediately carried before the Lord Mayor, or other Justice of the Peace, and prosecuted."

For an explanation of Lady Day, click here

For an explanation of Michaelmas, click here.

#13

Holcroft, Nicholson and the C18th gig economy

September 3rd, 2017share this

While the phrase ‘gig economy’ has been all over the mainstream media recently with the publication of the Good Work: The Taylor Review of modern working practices, the expression has been around for nearly a decade and insecure working arrangements have been around for centuries. In 2015, The Financial Times chose the expression for its FT 2015 Year in a Word, by Leslie Hook.

Leslie traced the expression back to the height of the financial crisis in 2009, ‘when the unemployed made a living by gigging, or working several part-time jobs, wherever they could’ with the word ‘gig’ emanating from jazz club musicians in the 1920s.

I could not help noting the similarities with life for many in the 18th Century as I re-read the Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft by William Hazlitt. Holcroft was a good friend of Nicholson, and his early employment history included time as a shoemaker, a stable lad at Newmarket, and as a chorister where he earned the nickname ‘the sweet singer of Israel’.

Holcroft headed for London where, like many young people today, he ‘felt the effects of poverty very severely’ and ruminated on what might have resulted from a good education. He was getting so desperate for work that he was heading to the office which recruited soldiers for the East India Company when he bumped into a friend who mentioned an opportunity with a travelling theatre company in Dublin. Then, for several years, he traipsed about the country in search of one opportunity after another before finally settling in London as a writer and dramatist.

Nicholson too was no stranger to the gig economy, having first worked for Josiah Wedgwood on a 'consultancy assignment' to Amsterdam to investigate financial irregularities with the Dutch sales agency. This had led to an employed position in Amsterdam, but only for a discrete project and so Nicholson had to return to London in search of work.

When young William Nicholson came to lodge with Holcroft at Southampton Buildings in around 1780, Holcroft subcontracted bits of writing to him. He also tried to persuade Nicholson that ‘at least as much revenue could be obtained from literary publications, as from any of the objects … of his thoughts.’

Over 25 years, Nicholson successfully built a steady income from writing, translating and publishing. But, with a large family to feed, he also took several gigs on the side. Projects included consulting on technical issues, sometimes as an early patent agent, acting as Secretary to the Chapter Coffee House Society and the General Chamber of Manufacturers. Then in the mid-1800s, he took on assignments as a civil engineer for a couple of water supply projects.

Unfortunately, like many who operate in the gig economy today, Holcroft and Nicholson did not set aside enough of their incomes during the good times to provide for ill-health in their old age.

The gig economy is not such a new phenomenon, but it does remind us that workers did not always enjoy the social safety nets that we often take for granted and are comparatively recent developments in the history of employment:

•1908 – old age pension introduced for men over 70

•1938 – paid holiday introduced

•1940 – old age pensions introduced for women

•1948 - the NHS was introduced.

#12

Josiah Wedgwood’s advice on international trade negotiations …January 1786

August 3rd, 2017share this

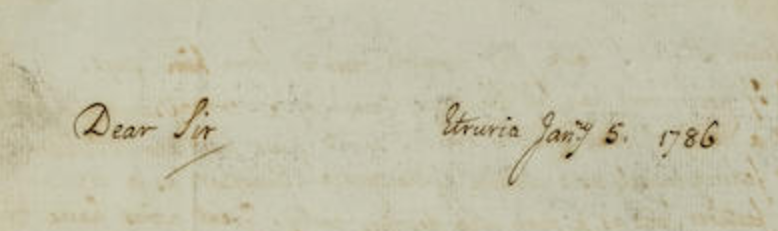

When Josiah Wedgwood was invited to chair the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he remembered the able young man who had served him well in the Netherlands in the 1770s, and invited William Nicholson to serve as his secretary.

International trade was a fundamental concern of the Chamber, as it is today, and it was interesting to come across this letter online which had been auctioned by Bonham’s in 2004.

Wedgwood wrote to the Rt Hon William Eden who was about to depart to France to negotiate a trade treaty, with this simple request:

“With regard to our particular manufacture, we only wish for a fair and simple reciprocity, and I suppose (but I speak without any authority) that our Manchester & Birmingham friends would be willing to give & take in the same way...”

http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11288/lot/144/?page_lots=8&upcoming_past=Past

#11

2017 Hull City of Culture / 1777 Wedgwood Shipping

April 13th, 2017share this

Imagecourtesy of MyLearning.org © Hull Museums

Our son is working in Hull, so with it being Hull’s year as the City of Culture we decided to tread the tourist trail on a recent visit and enjoyed a tour of the Maritime Museum.

I am always struck by how busy sea ports appeared in paintings from the seventeenth and eighteenth century and this image of Hull’s first port particularly caught my eye. It was built between 1775 and 1778, creating the largest port in Britain. The dates rang a bell as I knew that Wedgwood was shipping his pottery to Amsterdam from Hull just the year before.

In May 1777, Nicholson was working as Josiah Wedgwood’s agent in Holland where he was responsible for negotiating the transfer of the pottery business to Lambertus van Veldhuysen. Nicholson wrote to Thomas Bentley on 20 June 1777 that van Veldhuysen:

‘expects all future orders to be expeditiously forwarded & shipped at Hull at the charge of Mr Wedgwood, or at London when haste is required.’

Van Veldhuysen’s agent in Hull was Thomas Horwarth.

1777 was also the year that the Trent and Mersey canal was completed, allowing Wedgwood to convey his pottery to Hull via the waterways and thereby reduce the number of breakages.

By 1783, over 13 million pieces of pottery and earthenware were being exported via Hull (not all Wedgwood).

#6

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787)

March 20th, 2017share this

In December 1780 in the Chapter Coffee House near St Paul's Cathedral, several men led by the Irish chemist Richard Kirwan decided to meet fortnightly to discuss ‘Natural Philosophy, in its most extensive signification’.

The membership of the group grew steadily, and meetings took place in a variety of locations including the Baptist’s Head Coffee House. William Nicholson joined in 1783 and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

Nicholson’s copy of the minutes of the society, until 1787 when it folded, are in Oxford’s Museum of the History of Science and it was wonderful to be able to inspect them recently.

Compared to other philosophical societies of that time, especially the Lunar Society which had been meeting in the Midlands since 1765, this group seems little known – partly because it never had any name.

In 1785 it was agreed that the group would have no formal name when Kirwan ‘affirmed that the society not being desirous of that kind of distinction which arises from name or title were so far from giving any sanction or authority to the names used by their secretaries that the original determination in this respect was that the society should not have a name.

Fortunately the minutes do include a most interesting list of 35 members (the total number of members over the life of the society was 55).

Mr Alex Aubert (1730-1805), Austin Friars, 26

MrWilliam Babbington(1756-1833)

MrAndrewBlackhall (?-?), Thavies Inn, Holborn

DrWilliamCleghorn(1754-1783), Haymarket, 11

DrJohnCooke(1756-1838)

DrAdairCrawford(1748-1795), Lambs Conduit Street, 48.

MrJean-Hyacinthde Magellan(1722-1790), Nevilles Court, 12

MajorValentineGardiner(1775-1803)

DrWilliamHamilton(1758-1807)

MrJamesHorsfall(-d1785), Inner Temple.

DrJohnHunter(c1754-1809), Leicester Square

DrCharlesHutton(1737-1823)

MrWilliamJones(1746-1794), Inner Temple

DrWilliamKeir(1752-1783), Adelphi

MrRichardKirwan(1735-1812), Newman Street, 11

DrWilliamLister(1756-1830)

MrPatrickMiller(1731-1815), Sackville Street, 17

MrEdwardNairne(1726-1806), Cornhill, 20

MrWilliam Nicholson(1753-1815)

DrGeorgePearson(1751-1828)

DrThomasPercival(1740-1804)

DrCharles William Quin(1755-1818), Harmarket, 11

DrJohnSims(1749-1831), Paternoster Row, 11

MrBenjaminVaughan(1751-1835), Mincing lane

MrAdamWalker(c1731-1821), George Street, Hannover Square

DrWilliam CharlesWells(1757-1817), Salisbury Court

MrJohnWhitehurst(1713-1788), Bolt Court, 4

DrJohnWatkinson(1742-1783), Crutched Friars, 22

Honorary members

DrMatthewBoulton(1728-1809), Birmingham

MrRichardBright(1754-1840), Bristol

MrJamesKeir(1735-1820), Birmingham

DrRichardPrice(1723-1791), Newington Green

Rev'd DrJosephPriestley(1733-1804), Birmingham

MrJamesWatt(1736-1819), Birmingham

MrJosiahWedgwood(1730-1795), Etruria

Further information

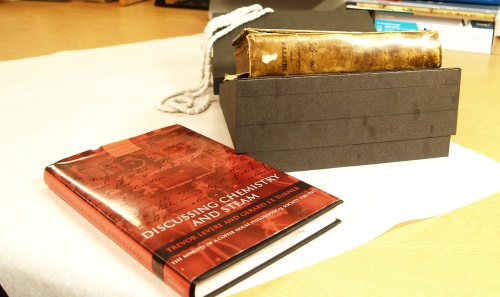

The entire set of minutes, as well as descriptions of all the members of the society, are set out in Discussing Chemistry and Steam: The Minutes of a Coffee House Philosophical Society 1780-1787, by Trevor H. Levere and Gerard L'E Turner.

Available from Oxford University Press

#5

STEM for girls - and how this biography might never have been started

February 3rd, 2017share this

Wedgwood-Museum-in-Barlaston-pic-by-Tom-Pennington-under-creative-commons

One of the questions that I am most frequently asked is how on earth I happened to be writing a book about an eighteenth-century scientist.

Colleagues tend not to be surprised that I am writing a book, as I have always written and published a great deal as part of my career in marketing. But friends and family who have known me since my school days will have witnessed a fundamental aversion to science, particularly biology (too gory) and chemistry (too smelly). I remember my science teacher as being very kind and patient, but cutting open worms and frogs and foul-stinking experiments could never capture my imagination. I hope the S in STEM is more inspiring these days.

On the other hand, history and languages had me in thrall. How could you not want to set sail with the explorers? Or imagine the thrill of inventing the steam engine or designing the first iron bridge and seeing it built? How wonderful to design an intricate piece of pottery and for it to come out of the kiln just as you had planned. I have always maintained an interest in industrial heritage and volunteered with the charity Arts & Business to help two industrial museums in the early 1990s, one of which was the Gladstone Pottery.

Luckily, my very first encounter with Nicholson was in my teens when my grandfather showed me the log book from Nicholson’s voyage to China on the Gatton in 1771. It was like having my own Marco Polo in the family.

This fact was buried deep in the recesses of my mind until around 2009 when I remembered Nicholson and his connection with Josiah Wedgwood, prompted by the Museum winning the Art Fund Prize as Museum of the Year and the financial failure of the Wedgwood business being much in the news. As this was all less than ten miles from my home, it seemed sensible to see if there might be any evidence of Nicholson’s employment by Wedgwood before the collection was dispersed – as was threatened at the time.

Sadly, I could find no employment contract or even payslips – but there was a wealth of correspondence between Nicholson and Josiah Wedgwood or his partner Thomas Bentley in regards to affairs of the agency in Amsterdam. Then later, between 1785 and 1787 Nicholson was secretary to Wedgwood at the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain (about which I will write another day).

I need to confess that it was some time before I learnt of Nicholson’s scientific works, and if my first encounter had been with anything to do with chemistry I would have backed right off.

But finding a direct connection to one of the heroes of marketing (Wedgwood is known as a father of modern marketing) and a major player in the industrial revolution - I was hooked and needed to know more.

#2

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order