Eighteenth Century Mr Nicholson launches his YouTube Channel

December 15th, 2020share this

When William Nicholson launched his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts in 1979, part of his motivation was to speed up the transfer of scientific knowledge.

If he lived today, he would surely have embraced social media for that purpose - never lowering himself to insults or trolling!

Now he has added a Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account to his media channels, and we are able to share excerpts from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ a performance for the Bloomsbury Festival 2020 which took place in the open air of St George’s Gardens, London where Nicholson is buried.

Directed and introduced by Ian Brown, episode one is the historical part where his biographer Sue Durrell interviews Nicholson who has returned from his grave in the gardens to talk about his life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nicholson is brought to life most ably by actor Julian Date, who reminisces about his life at the crossroads of Georgian arts, literature, science, and commerce, and discusses the importance of his discovery in splitting water using Volta’s battery, alongside his friend Dr. Carlisle.

The short three excerpts in this video cover:

• Working for Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam and at the General Chamber of Manufacturers

• Nicholson’s motivation for launching his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts; and

• Remembering Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution and recalling the experiment with Anthony Carlisle where they split water into hydrogen and oxygen in May 1800.

This is the first of two videos from this event. Part two shows demonstrations of the experiment and discusses its implications in the quest for clean energy.

Julian Date is represented by Hilary Gagan Associates.

#36

Mary Wollstonecraft, PPH and eighteenth century maternal care

November 26th, 2020share this

With all the fuss about the Mary Wollstonecraft statue, it reminded me that one of the topics which was on my mind was the state of maternity care at the end of the eighteenth century. William and Catherine Nicholson seemed to do pretty well with at least 10 kids making it to adulthood. (One infant death is recorded, one of the twelve children still remains a mystery).

Caitlin Moran’s response on Twitter to the statue in Newington Green was ‘If you want to make a naked statue that represents "every woman", in tribute to Wollstonecraft, make it e.g. a naked statue of Wollstonecraft dying, at 38, in childbirth, as so many women did back then - ending her revolutionary work. THAT would make me think, and cry.’{10 November 2020}

So, I turned to Lisetta Lovett, a retired consultant psychiatrist and medical historian, and asked whether this standard of maternal care was normal for the time? Or was Mary Wollstonecraft just particularly unlucky in her medical advisers?

The information which I had compiled on the birth of Mary’s baby with William Godwin was that:

Mary went into labour on Wednesday 30 August, choosing to hire a midwife but no nurse. Godwin described the role of the midwife ‘in the instance of a natural labour, to sit by and wait for the operations of nature, which seldom in these affairs demand the operation of art.’

Little Mary was born at 11.20pm and, sometime after 2.00am, Godwin who was keeping out of the way in the parlour, was informed that the placenta had not been removed. A physician was called for and he removed the placenta ‘in pieces’. The loss of blood was ‘considerable’ and Mary’s health did not improve over the next few days, despite a second doctor visiting and pronouncing that Mary was ‘doing extremely well’.

Godwin wrote that ‘On Monday, Dr Fordyce forbad the child having the breast, and we therefore procured puppies to draw off the milk.’

Then on Wednesday, following a recommendation by family friend Dr Carlisle, ‘it was now decided that the only chance of supporting her through what she had to suffer, was by supplying her rather freely with wine … I neither knew what was too much, nor what was too little. Having begun, I felt compelled under every disadvantage to go on. This lasted for three hours.’

Dr Fordyce was no beginner - see wikipedia - although we do not know if he was the attending doctor on the first two occasions. Dr Carlisle was a close family friend who went on to become the Surgeon Extraordinary to King George IV in 1820.

Lisetta, whose book Casanova's Guide to Medicine: 18th century Medical Practice is due to be published by Pen and Sword Ltd in April 2021, kindly provided the following insights into the medical profession and the little that we know about Mary Wollstonecraft’s death:

The information given here, taken from William Godwin’s diary as well as other sources, raises more questions than it answers. However, it looks like Mary suffered from a post-partum haemorrhage, the cause of which seems to have been a retained placenta.

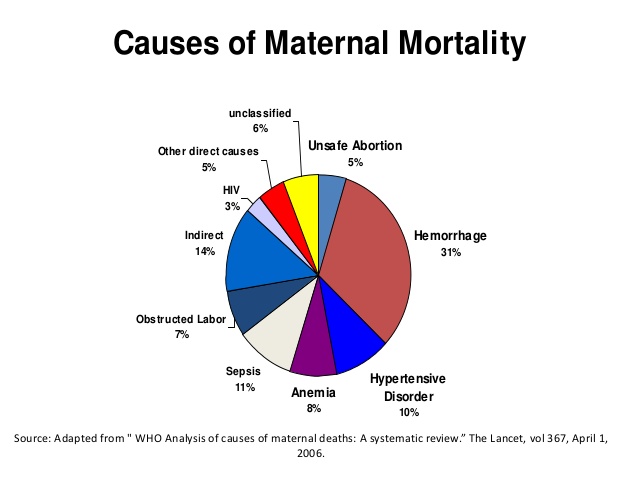

The medical definition of a retained placenta is one that has not been expelled within 30 minutes of delivery. This is still a leading cause of maternal death worldwide, and treatment today is intervention with oxytocin either in the third stage of labour or after delivery and, if this fails, then manual removal under anaesthesia.

By the 19th century, obstetrics had become a medical specialty in its own right, much to the irritation of the midwives. Following the advent of man-midwives, medical doctors moved into the specialty. Neither Dr Fordyce or Dr Carlisle are recorded as having such expertise, but maybe this is not so surprising given that obstetrics as a medical specialty developed a little after their time.

There is a telling quote from a Dr Edgell in On Obstetric Practice, in 1816: "I believe it was an aphorism of the late Dr Clarke, that no woman should die of haemorrhage if an accoucheur is called early...".

Post-partum haemorrhage was a well recognised and potentially lethal complication of child-birth. Accoucheurs applied a variety of treatments to manage it and knew that a quick response could be life-saving. These treatments ranged from a hand in the uterus to stimulate contraction of the uterus and therefore expel the retained placenta (see Davis David in Principles and Practice of Obstetrics 1832-65) to the use of cold water on the stomach, or even injected in the rectum.

The obstetric literature of the early 19th century reveals that there was a lot of medical debate about what measures were most effective, including whether stimulants like brandy or wine should be administered. As the Covid pandemic illustrates, doctors are often in disagreement and so we should not be surprised.

Clearly, Mary would have been better off with an experienced accoucheur, medically trained or not, present throughout the birth ready to respond to any complications. The midwife at least knew that a retained placenta was bad news and informed Godwin who called for a physician. He tried to remove the placenta but probably did not do so completely; a difficult task without the benefit of an anaesthetic and a dreadful ordeal for Mary. For whatever reason, he did not continue to attend her which was a pity.

It is not clear if Mary continued to bleed or not but, given the second doctor's optimism, it sounds as if the bleeding appeared to have stopped.By the time Dr Fordyce is called, it is four days post-partum! He may have suggested the puppies in order to stimulate the uterus to contract and thereby encourage the expulsion of any remaining placenta as suckling induces the body to produce oxytocin. But why not allow the baby to suckle Mary?

Perhaps, she already had a wet nurse, and the doctor wanted to avoid disruption to the baby's feeding. That being said, the cult of breast-feeding your own baby had become popular in the 18th century especially in France where Rousseau’s re-evaluation of maternity was influential. Mary had spent several turbulent years living in France and was no doubt aware of this.

Mary obviously was deteriorating, in part because she continued to lose blood (perhaps internally so it was not obvious) leading to severe anaemia. She may have also developed septicaemia although there is no mention of her having a fever. Ironically, one cause of this could have been manual placental removal. At this time there was little, if no notion, of the importance of keeping one’s hands clean to prevent dissemination of germs.

When Carlisle finally sees her, I think he knows she is going to die and this is why he suggests wine as a 'tonic', not as a treatment but rather as an anaesthetic to make her last hours a little more bearable.

Godwin must have bitterly regretted his early laissez faire comment about childbirth. It is a great pity that he had not employed from the outset an experienced accoucheur, although even so Mary might have died. At this time, childbirth was one of the most dangerous challenges a woman might be obliged to address.

You can follow Lisetta Lovett on her blog Casanova's Medicine.

Today, according to the WHO, about 14 million women around the world suffer from postpartum haemorrhage every year. This severe bleeding after birth is the largest direct cause of maternal deaths. And of course, in addition to the suffering and loss of women’s lives, when women die inchildbirth, their babies also face a much greater risk of dying early. Shockingly, 99% of the deaths from PPH occur in low- and middle-income countries, compared with only 1% in high-income countries.

#35

Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture and the feminists’ new clothes

November 15th, 2020share this

I guess I feel that I have a very small right to claim a connection to Mary Wollstonecraft, as my 5 x great grandmother Catherine Nicholson was one of the two close friends (along with Eliza Fenwick) who stayed with and comforted Mary Wollstonecraft in her dying days.

Catherine wrote to William Godwin after his wife’s death to say:

Myself and Mrs Fenwick were the only two female friends that were with Mrs Godwin during her last illness. Mrs Fenwick attended her from the beginning of her confinement with scarcely any interruption. I was with her for the four last days of her life …

She was all kindness and attention & cheerfully complied with everything that was recommended to her by her friends. In many instances she employed her mind with more sagacity upon the subject of her illness than any of the persons about her …

I noticed the fundraising appeal for the statue in 2019 – but it was not clear how much they were trying to raise; how much was still needed; and how it would be spent. There was no information about the finances on the website, only the vague statement “A capital sum for the memorial and a revenue source for the Society will ensure that Wollstonecraft’s legacy and learning will continue.” I was simply seeking to clarify the financial position, but my polite enquiry elicited a rather frosty response, suggesting that I should find another memorial to support.

I’m a fan of figurative sculptures and am lucky enough to live near to the National Memorial Arboretum. As you walk round, you cannot fail to be moved by the way that the sculptures make a historic figure lifeisize (or larger) making more real the boy who represents all those shot at dawn, thechild evacuees, or the ladies Women’s Land Army and Timber Corps. I’d never heard of lumber jills before, but seeing the memorial prompted me to find out more.

So, OK I’ll admit that I’m not very radical in my taste for sculptures, And Mary Wollstonecraft was a radical, so she needs a radical sculpture – right?

Mary Wollstonecraft was strong and adventurous, working as a journalist she headed off to Paris to cover the revolutionary troubles for the publisher Joseph Johnson. But, I’m afraid I cannot see strength and courage in this sculpture.

She was a thinker, an author, and an educator. How is this portrayed in the sculpture? And how is it meant to inspire young women toexpand their minds?

The Mary on the Green website states that “Her presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people in Islington, Haringey and Hackney” … and The Wollstonecraft Society’s objectives are “to promote the recognition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s contribution to equality, diversity and human rights.”

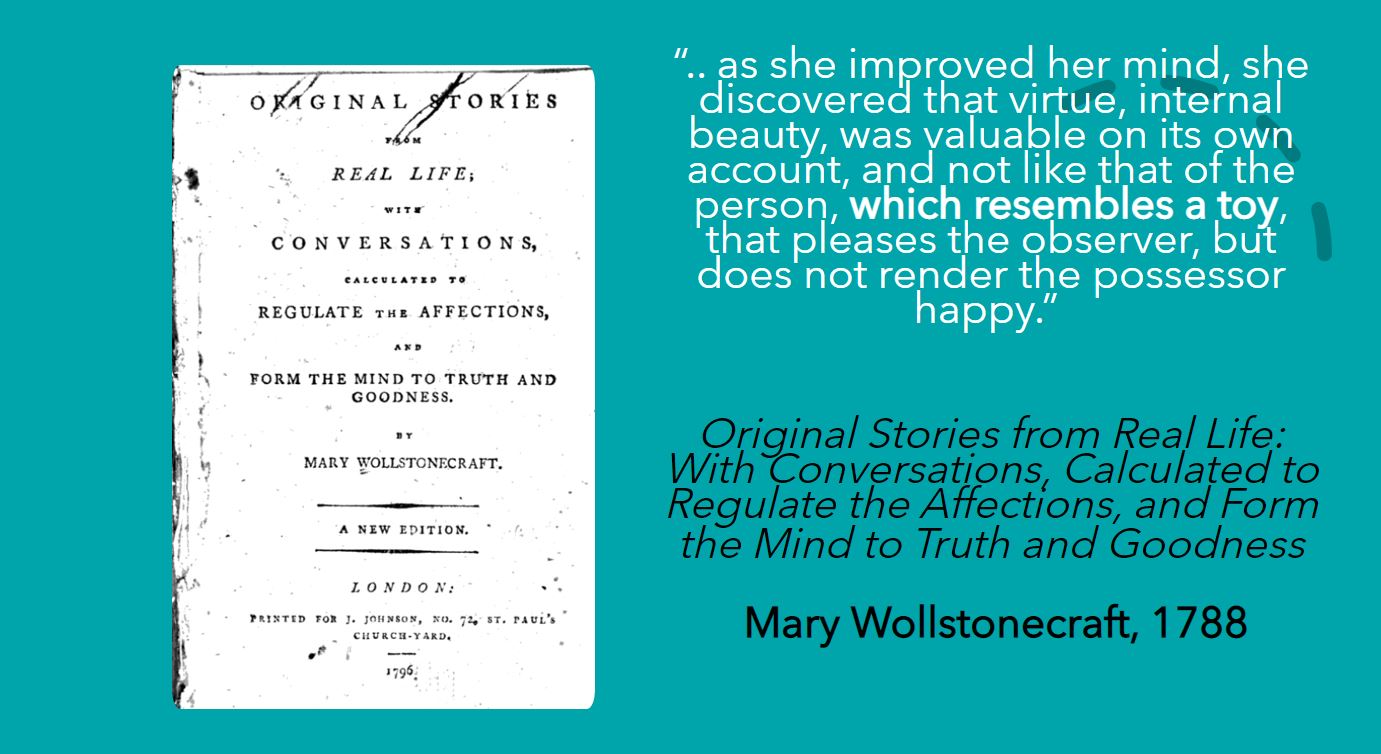

In Original Stories from Real Life: With Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (1788), Wollstonecarft wrote of a woman who lost her good looks to the small pox and “.. as she improved her mind, she discovered that virtue, internal beauty,was valuable on its own account, and not like that of the person, which resembles a toy, that pleases the observer, but does not render the possessor happy.”

I’m struggling to see how any child who sees this toy-like sculpture will come away with the message that cultivating the mind is more valuable than looks.

On the other hand, (having once accompanied a group of 11-year olds on a school trip to Paris) it is not hard to imagine the giggling and sexist comments that might emerge among some and the embarrassment that might be felt by others.

I don’t envy the teacher who has to create a lesson plan around this educational trip!

#34

Carlisle and the Literary Fund save Nicholson from a pauper’s funeral

January 8th, 2020share this

Driving along at lunchtime today, Radio 4 reported on the number of public health funerals being paid for by local authorities at an average cost of £1,403.

Often called a pauper’s funeral, nowadays the local authority will pay for a basic burial when there is no family, or the family cannot afford to pay for funeral arrangements. There have also been stories in the media of people crowdfunding the cost of a funeral.

Neither of these were an option for Catherine Nicholson,when her husband William died at their home in Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury on Monday 21May 1815.

Their eldest son had left home to work in North Yorkshire, for Lord Middleton, but described how ‘My brother remained with him to the last and Carlisle attended him.’

Old friend, and co-discoverer of electrolysis, Anthony Carlisle was at this time the Professor of Anatomy of the Royal Society and in this same year, he was appointed to the Council of the College of Surgeons where for many years he was a curator of their Hunterian Museum.

Nicholson reportedly drank nothing except water since he was twenty years of age, which Carlisle said was the cause of his kidney problems

Despite his sober approach to life and earning well above average for the time, there were also substantial outgoings for ‘a family often or twelve grown up people, adequate servants and a house like a caravansary.’

On the day of Nicholson’s death, Carlisle saw the impoverished circumstances of the family and appealed to John Symmonds at the Literary Fund (now the Royal LiteraryFund) to help:

‘Poor Nicholson the celebrated author, and man of science, died this morning. His family are in the deepest poverty, and I doubt even the credit or the means to bury him.’

I have set a person to apply to the Literary Fund, pray second that application and recommend it to their bounty to be as liberal as their affairs and their rules will permit.’

The next day John Symmonds voted through a grant of £21 for Catherine Nicholson in respect of Nicholson’s talents and industriousness, writing ‘I am extremely desirous that something should be done, most necessarily of that society’ … ‘As he neither prepared for his dispatch, you are written that no time must be lost’.

Once funeral costs were paid, £21 cannot have lasted long, and Catherine Nicholson moved to 11 Grange Street from where she wrote to thank the Literary Fund for ‘the generous respect they were pleased to have for her late husband's abilities’.

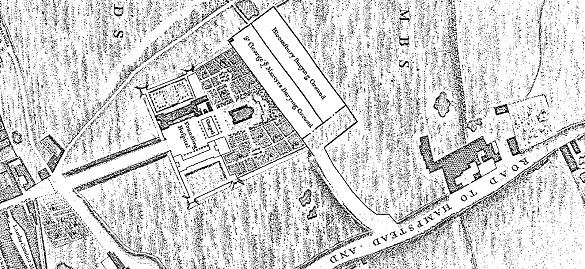

Nicholson was buried on 23 May 1815 in St George’s Gardens, Bloomsbury, one of the first burial grounds to be established at a distance from its church due to the growing problem of overcrowding in London graveyards.

#27

The Enlightenment Flyfishers (first published in Flyfishers' Journal)

July 12th, 2018share this

'Angling - Preparing for Sport': published in 'British Field Sports' in 1831, this copper-engraved print depicts the kind of fishing tackle and clothing which would have been familiar to Sir Humphry Davy's literary characters Halieus, Ornither, Poietes and Physicus.

Salmononia: or Days of Fly Fishing, first published in 1809 by the Cornish chemist and inventor Humphry Davy (1778-1829), is one of the most collectable of angling books from the early nineteenth century. It was dedicated to the Irish physician and mineralogist, William Babington, a longstanding friend of Davy and a fellow founder of the Geological Society of London in 1807.

The book, written while Davy was ill, takes the form of a series of discussions between four imaginary characters: Halieus, the accomplished fly fisher; Ornither, a county gentleman who has done a little fishing; Poietes, a fly-fishing nature-lover; and Physicus a natural philosopher who has never fished.

John Davy, in his Memoirs of the Life of Humphry Davy, paints a wonderful picture of his brother on the river:

"I am sorry I have not a portrait of him in his best days in his angler’s attire. It was not unoriginal, and considerably picturesque – a white, low-crowned hat with a broad brim; its under surface green, as a protection from the sun, garnished, after a few hours’ fishing, with various flies of which trial had been made, as was usually the case; a jacket either grey or green, single-breasted, furnished with numerous large and small pockets for holding his angling gear; high boots, water-proof, for wading, or more commonly laced shoes; and breeches and gaiters, with caps to the knees made of old hat, for the purpose of defence in kneeling by the river side, when he wished to approach near without being seen by the fish; such was his attire, with rod in hand, and pannier on back, if not followed by a servant, as he commonly was, carrying the latter and a landing net."

Humphry Davy admits that Salmononia was inspired by ‘recollections of real conversations with friends’ and John’s memoir revealed that Halieus was inspired by William Babington. But whose conversations inspired the other characters?

Two friends of both Davy and Babington that must be strong contenders are William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840). They are best known for their decomposition of water into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis, achieved in 1800 with a copy of Alessandro Volta’s recently invented pile – a discovery which so excited Davy that he wrote that: ‘An immense field of investigation seems opened by this discovery: may it be pursued so as to acquaint us with some of the laws of life!’

Davy met Nicholson when he arrived in London, having already corresponded and sent his first scientific papers to him in 1799 for publication in A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first monthly scientific publication in Britain, running between April 1797 and December 1813. Over the course of its life, Nicholson’s Journal included some twenty articles on fish (but not specifically fly fishing). The most important was the editor’s own in the article on the torpedo fish in 1797, which speculated about the source of the electric charge within the pelicules of the torpedo, and which inspired Volta to try the various combinations of discs (an important hint) resulting in the development of his battery pile. When Davy was appointed as Director of the Royal Institution, aCommittee for Chemical Investigation and Analysis was established, on which Nicholson was invited to participate.

Nicholson had known Babington since 1784 when they were joint secretaries of a philosophical coffee house society established by Richard Kirwan, another Irish chemist and geologist. He also knew Carlisle, then at Westminster hospital, through his close friend the radical author William Godwin whose wife Mary Wollstonecraft was attended by the surgeon before she died in 1797.

Unfortunately, we don’t have an account of Davy, Babington, Carlisle and Nicholson fishing together, but it is a scene that we might easily imagine.

Nicholson, who was a prolific publisher, in his 1809 British Encyclopedia, or Dictionary of Arts and Sciencesdescribes fly fishing as ‘an art of so much nicety, that to give any just idea of it, we must devote an article to it.’ Sadly, he does not write about fly-fishing as eloquently as he does about chemistry, simply describing a number of flies and his only advice on how to fish is ‘keep as far from the water’s edge as may be, and fish down the stream with the sun at your back, the line must not touch the water.’

But, in a memoir of The Life of William Nicholson, the manuscript of which has finally been published 150 years after it was written, there is a charming account by Nicholson’s son of fishing trips with Carlisle in around 1803:

"Carlisle was at that time about thirty years of age, good looking and active …

Having passed his early days at Durham and in Yorkshire, Carlisle was fond of the country and country sports. We had many a day’s fishing at Carshalton, where his intimacy with the Reynolds and Shipleys procured him the use of part of the stream where the public were excluded. He was a skilful fly fisher and during the day I generally carried the pannier and landing net, but towards night when the mills stopped, and the water ran over a bye-wash, I with my bag of worms and rod managed to hook some fish as big as were taken during the day.

We also had fishing grounds at a place in Hertford called Chenis which was rented as I understood by Carlisle and a fellow sportsman called Mainwaring. These two gentlemen and myself as a third in a post-chaise used to start at 6.00 o’clock am, breakfast at Ware or Hoddesdon and forward to the fishing, which was fine for a boy of fourteen. And then Mr Mainwaring always took a fowling piece with him and occasionally shot a bird which was worth all the fish, rods and lines and all.

Chenis was a remarkably quiet rural place and the little inn we slept at was situated in a settlement of some half dozen cottages and houses, but what its name was I do not know. On one occasion when our companion was called away Carlisle and I remained there for a day or two. We were very successful in our fishing and were about to depart when it turned out there was a county election going forward and there was no conveyance to be had for love or money. Carlisle was wanted at home and we had no choice but to start on foot, so away we went after breakfast with a boy to show us a footpath way through fields to Rickmansworth where we hoped to get some conveyance to London.

Carlisle had the best share of the luggage and the boy and I the remainder. The country we travelled was beautifully undulated and of a dry sandy soil. It was very hot and I suspect I was the first to feel fatigue. After a long trudge we stopped at a gate leading into a sandy lane and looking back at the hillside I was amazed at the display of poppies in full bloom, the whole field was a mass of crimson, a new sight to me.

I was very thirsty and tired and have often thought of that field and Burns’ immortal lines:

Pleasures are like poppies spread;

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

or like the snow fall on the river.

a moment white then melts forever.[1]

But time, like a pitiless master, cried onward and we had to trudge again. At last our guide left us on the dusty high road to Rickmansworth, where in time we arrived. Here we got some refreshment and awaited til a return post-chaise conveyed us to London. We had walked nearly 30 miles and it was my first walking adventure of any magnitude."

The story was written when young Nicholson was eighty, and his geography seems a bit muddled – I have been unable to locate a place called Chenis, in Hertford – but records exist for one in Buckinghamshire in the 1770s. Could he mean the river Chess if he was near Ware and Hoddesdon? The Chess also passes near a village called Chenies just a few miles from Rickmansworth. (If any readers of the Flyfishers’ Journal can help, I would be very interested to hear from them.)

Carlisle went on to enjoy a stellar medical career, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1804, where he became Professor of Anatomy 1808 to 1824.

In 1809, he published an account of some experiments into how fish swam, by cutting various fins off seven fish each of dace (cyprinus leusiscus), roach (cyprinus rutilus), gudgeon (cyprinus gobio) and minnow (cyprinus phoxinus). He recorded how, on removal of the pectoral fin [2] its progressive motion was not at all impeded, but it was difficult for the fish to ascend; on removing the abdominal fin as well, the fish could not ascend; on removing the single fins, ‘produced an evident tendency to turn around, and the pectoral fins were kept constantly extended to obviate that motion; … and so on, until all fins had been removed from the seventh fish which cruelly ‘remained almost without motion’.

Carlisle was appointed Surgeon Extraordinary in 1820 to King George IV and was knighted in 1821. He died in 1840, never losing his love of fishing.

"Sir Anthony Carlisle had been called into the Prince Regent mainly to consult as to what wine he should drink. Having ascertained that brown sherry was the favourite of the day, he recommended it and gave great satisfaction.

Carlisle wrote to me, while I was engaged in a survey in Yorkshire, to find him a handy honest unsophisticated lad as a servant. I did my best and sent him one. The lad turned out a stupid dog, but when I visited London a short time afterwards and dined with Carlisle this boy waited and amused me by incessantly answering Carlisle ‘Yes Sir Anthony, … no Sir Anthony’ and ‘Sir Anthony’ at the beginning, middle and end of every sentence. All this passed as a matter of course and reminded me how calmly we bear our dignities when they fall upon us.

Carlisle was a true fisherman and a great admirer of honest Izaak Walton and used to quote from that delightful book The Compleat Angler, so that when any food or wine was better than common he said ‘it was only fit for anglers or very honest men’; and then he had another joke when we got thoroughly wet on our fishing excursions, saying ‘it was a discovery, how to wash your feet without taking off your stockings’."

#24

[1] From Robert Burns, ‘Tam o’ Shanter’, Edinburgh Magazine, Mar 1791.

[2] All these articles can be found by searching the index.

Thomas Holcroft – Landlord and long-time friend (part 1)

May 9th, 2018share this

Towards the end of the 1770s, after returning to London from his work for Wedgwood in Amsterdam, William Nicholson took lodgings with the writer Thomas Holcroft and was introduced to his landlord’s colourful circle of friends. A fellow lodger was Elizabeth Kemble whose father had established a strolling theatre company, and whose sister Sarah Siddons was a well-known actress.

From their rooms in Southampton Buildings at the top of London’s Chancery Lane, Holcroft and Nicholson often headed down to ‘Porridge Island’ a small row of cook-shops near to St Martins-in-the-Field where they enjoyed a nine-penny dinner and met up with other writers and musicians.

According to his son, Nicholson wrote a great deal for Holcroft who was used to having an amanuensis. The first piece of work to which Nicholson is know to have contributed was a novel published in 1780 entitled Alwyn: or The Gentleman Comedian. William Hazlitt, who completed Holcroft’s memoir (with assistance from Nicholson) explained how ‘it was originally intended that N.... should compile from materials to be furnished by Holcroft, but of which he in fact only wrote a few short letters, evidently very much against the grain.’

The second piece of work, which was attributed to Nicholson, was the prologue to a drama called Duplicity. The play opened in October 1781 at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, and the prologue was performed by Mr Lee-Lewes.

The opening performance was met with great applause and positive reviews. Holcroft described his feelings as ‘having escaped from the Dog of Hell, the Elysian fields are before me, if I have but taste and prudence to select the sweets.’ One can imagine the celebrations in Southampton Buildings that night and the excitement of Nicholson and his new bride as they mingled with the cast which included Elizabeth Inchbald, another renowned actress.

Unfortunately, within just a few days, Duplicity failed to generate enough revenue to cover the expenses of the house and Mr Harris of the Theatre Royal declared that ‘unless it was commanded by the King, he should not think of playing it any more’.

Nicholson’s son claimed that his father continued to produce ‘essays, poems and light literature for the periodicals of the day’ while working with Holcroft, but frustratingly for us ‘to none of which he put his name’.

A couple of years later, after war with France had ended, Holcroft made his name with the unscrupulous infringement of another playwright’s intellectual property. Having travelled to Paris to see The Marriage of Figaro by Beaumarchais, Holcroft had requested a copy of the script but was refused. So, over ten nights in September 1784, he and a friend attended the performance and recorded the entire script. In December that same year, with no respect for creative copyright, Holcroft took to the stage at Covent Garden in the role of Figaro for its first performance in Britain.

A decade later in 1792, Holcroft produced his best-known play The Road to Ruin. Let us leave Holcroft to bask in his glory for a little while, and I will return to his life after 1792 in due course.

#23

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

FutureLearn MOOC - Humphry Davy: Laughing gas, literature and the lamp.

October 4th, 2017share this

A MOOC (for those of you like me who did not know what this was) is a ‘massive open online course’, and Lancaster University and the Royal Institution of Great Britain are hosting one about Humphry Davy which will start on 30 October 2017.

The course will run for four weeks. Learners will typically spend three hours per week working through the steps, which will include videos (filmed on location at the Royal Institution), text-based activities and discussion, and quizzes. Learners will be guided at all stages by a specialist team of educators and mentors. It's entirely free to participate, and no prior knowledge of Davy is required.

Humphry Davy was a good friend of William Nicholson and they were both keen disseminators of knowledge, so would encourage you to spread the word to anyone who might be interested.

In 1797 young Davy had ‘commenced in earnest his study of natural philosophy,’ but this ‘soon gave place to that of chemistry’ and in his note book he recorded that his first experiments ‘were made when I had studied chemistry only four months, when I had never seen a single experiment executed, and when all my information was derived from Nicholson’s Chemistry, and Lavoisier’s Elements.’ (style='"Times New Roman",serif;' (Davy and Davy, The Collected Works,1839.)

Then in the Spring of 1799, Davy made contact with Nicholson sending two articles to include in A Journal of Natural Philosophy and the Arts, both of which appeared in the May edition:

- Experiments and Observations on the Silex composing the Epidermis or external Bank, and contained in other Parts of certain Vegetables.

- Introductory to the Experiments contained the subsequent Article, and on other Subjects relative to the Progress of Science.

There is much more to tell about their relationship, but now is not the time, so let’s get back to the MOOC …

This FREE course is intended for anyone with an interest in Humphry Davy, or early nineteenth century literature, science, or history. It will explore some of the most significant moments of Davy's life and career, including his childhood in Cornwall, his work at the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol and the Royal Institution in London, his writing of poetry, his invention of his miners' safety lamp and the controversy surrounding this, and his European travels. The course will also investigate the relationships that can exist between science and the arts, identify the role that science can play in society, and assess the cultural and political function of science.

Free course – open to all - sign up today at

http://www.futurelearn.com/courses/humphry-davy

#14

Holcroft, Nicholson and the C18th gig economy

September 3rd, 2017share this

While the phrase ‘gig economy’ has been all over the mainstream media recently with the publication of the Good Work: The Taylor Review of modern working practices, the expression has been around for nearly a decade and insecure working arrangements have been around for centuries. In 2015, The Financial Times chose the expression for its FT 2015 Year in a Word, by Leslie Hook.

Leslie traced the expression back to the height of the financial crisis in 2009, ‘when the unemployed made a living by gigging, or working several part-time jobs, wherever they could’ with the word ‘gig’ emanating from jazz club musicians in the 1920s.

I could not help noting the similarities with life for many in the 18th Century as I re-read the Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft by William Hazlitt. Holcroft was a good friend of Nicholson, and his early employment history included time as a shoemaker, a stable lad at Newmarket, and as a chorister where he earned the nickname ‘the sweet singer of Israel’.

Holcroft headed for London where, like many young people today, he ‘felt the effects of poverty very severely’ and ruminated on what might have resulted from a good education. He was getting so desperate for work that he was heading to the office which recruited soldiers for the East India Company when he bumped into a friend who mentioned an opportunity with a travelling theatre company in Dublin. Then, for several years, he traipsed about the country in search of one opportunity after another before finally settling in London as a writer and dramatist.

Nicholson too was no stranger to the gig economy, having first worked for Josiah Wedgwood on a 'consultancy assignment' to Amsterdam to investigate financial irregularities with the Dutch sales agency. This had led to an employed position in Amsterdam, but only for a discrete project and so Nicholson had to return to London in search of work.

When young William Nicholson came to lodge with Holcroft at Southampton Buildings in around 1780, Holcroft subcontracted bits of writing to him. He also tried to persuade Nicholson that ‘at least as much revenue could be obtained from literary publications, as from any of the objects … of his thoughts.’

Over 25 years, Nicholson successfully built a steady income from writing, translating and publishing. But, with a large family to feed, he also took several gigs on the side. Projects included consulting on technical issues, sometimes as an early patent agent, acting as Secretary to the Chapter Coffee House Society and the General Chamber of Manufacturers. Then in the mid-1800s, he took on assignments as a civil engineer for a couple of water supply projects.

Unfortunately, like many who operate in the gig economy today, Holcroft and Nicholson did not set aside enough of their incomes during the good times to provide for ill-health in their old age.

The gig economy is not such a new phenomenon, but it does remind us that workers did not always enjoy the social safety nets that we often take for granted and are comparatively recent developments in the history of employment:

•1908 – old age pension introduced for men over 70

•1938 – paid holiday introduced

•1940 – old age pensions introduced for women

•1948 - the NHS was introduced.

#12

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal 355,451

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order