Eighteenth Century Mr Nicholson launches his YouTube Channel

December 15th, 2020share this

When William Nicholson launched his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts in 1979, part of his motivation was to speed up the transfer of scientific knowledge.

If he lived today, he would surely have embraced social media for that purpose - never lowering himself to insults or trolling!

Now he has added a Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account to his media channels, and we are able to share excerpts from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ a performance for the Bloomsbury Festival 2020 which took place in the open air of St George’s Gardens, London where Nicholson is buried.

Directed and introduced by Ian Brown, episode one is the historical part where his biographer Sue Durrell interviews Nicholson who has returned from his grave in the gardens to talk about his life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nicholson is brought to life most ably by actor Julian Date, who reminisces about his life at the crossroads of Georgian arts, literature, science, and commerce, and discusses the importance of his discovery in splitting water using Volta’s battery, alongside his friend Dr. Carlisle.

The short three excerpts in this video cover:

• Working for Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam and at the General Chamber of Manufacturers

• Nicholson’s motivation for launching his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts; and

• Remembering Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution and recalling the experiment with Anthony Carlisle where they split water into hydrogen and oxygen in May 1800.

This is the first of two videos from this event. Part two shows demonstrations of the experiment and discusses its implications in the quest for clean energy.

Julian Date is represented by Hilary Gagan Associates.

#36

Josiah Wedgwood’s advice on international trade negotiations …January 1786

August 3rd, 2017share this

When Josiah Wedgwood was invited to chair the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he remembered the able young man who had served him well in the Netherlands in the 1770s, and invited William Nicholson to serve as his secretary.

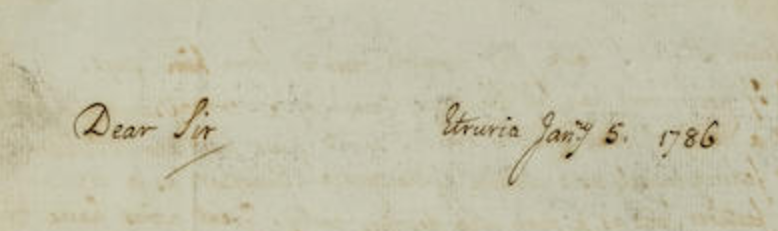

International trade was a fundamental concern of the Chamber, as it is today, and it was interesting to come across this letter online which had been auctioned by Bonham’s in 2004.

Wedgwood wrote to the Rt Hon William Eden who was about to depart to France to negotiate a trade treaty, with this simple request:

“With regard to our particular manufacture, we only wish for a fair and simple reciprocity, and I suppose (but I speak without any authority) that our Manchester & Birmingham friends would be willing to give & take in the same way...”

http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11288/lot/144/?page_lots=8&upcoming_past=Past

#11

STEM for girls - and how this biography might never have been started

February 3rd, 2017share this

Wedgwood-Museum-in-Barlaston-pic-by-Tom-Pennington-under-creative-commons

One of the questions that I am most frequently asked is how on earth I happened to be writing a book about an eighteenth-century scientist.

Colleagues tend not to be surprised that I am writing a book, as I have always written and published a great deal as part of my career in marketing. But friends and family who have known me since my school days will have witnessed a fundamental aversion to science, particularly biology (too gory) and chemistry (too smelly). I remember my science teacher as being very kind and patient, but cutting open worms and frogs and foul-stinking experiments could never capture my imagination. I hope the S in STEM is more inspiring these days.

On the other hand, history and languages had me in thrall. How could you not want to set sail with the explorers? Or imagine the thrill of inventing the steam engine or designing the first iron bridge and seeing it built? How wonderful to design an intricate piece of pottery and for it to come out of the kiln just as you had planned. I have always maintained an interest in industrial heritage and volunteered with the charity Arts & Business to help two industrial museums in the early 1990s, one of which was the Gladstone Pottery.

Luckily, my very first encounter with Nicholson was in my teens when my grandfather showed me the log book from Nicholson’s voyage to China on the Gatton in 1771. It was like having my own Marco Polo in the family.

This fact was buried deep in the recesses of my mind until around 2009 when I remembered Nicholson and his connection with Josiah Wedgwood, prompted by the Museum winning the Art Fund Prize as Museum of the Year and the financial failure of the Wedgwood business being much in the news. As this was all less than ten miles from my home, it seemed sensible to see if there might be any evidence of Nicholson’s employment by Wedgwood before the collection was dispersed – as was threatened at the time.

Sadly, I could find no employment contract or even payslips – but there was a wealth of correspondence between Nicholson and Josiah Wedgwood or his partner Thomas Bentley in regards to affairs of the agency in Amsterdam. Then later, between 1785 and 1787 Nicholson was secretary to Wedgwood at the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain (about which I will write another day).

I need to confess that it was some time before I learnt of Nicholson’s scientific works, and if my first encounter had been with anything to do with chemistry I would have backed right off.

But finding a direct connection to one of the heroes of marketing (Wedgwood is known as a father of modern marketing) and a major player in the industrial revolution - I was hooked and needed to know more.

#2

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order