Two precision clocks by Nicholson featured in Antiquarian Horology Journal

April 23rd, 2023share this

One of the most enjoyable things about researching Nicholson’s numerous interests and activities is the way that it has brought me into contact with so many people that I might never encountered otherwise. Experts in a variety of fields have been unbelievably kind and generous in sparing their time and energy to help me understand what Nicholson was up to and the context of his work at the time. One thing they all share has been a keenness to see that William Nicholson and his achievements should be better known and appreciated.

The most recent example is horological guru Jonathan Betts - Curator Emeritus at the Royal Observatory (National Maritime Museum), Greenwich, a horological scholar and author, and an expert on the first marine timekeepers created by John Harrison in the middle of the 18th century.

Jonathan is also the librarian to the Antiquarian Horological Society, and recently authored two articles about Nicholson which have been published in the society’s journal Antiquarian Horology, Vol 44, March 2023:

- ‘Two precision clocks by William Nicholson’; and

- ‘Notes from the Librarian: William Nicholson – so much more than a journalist.’

Forty years previously, in 1983, Betts had first encountered Nicholson (in regard to his comments on Explanations of Time-keepers Constructed by Mr Thomas Earnshaw and the late Mr John Arnold in 1806) and then in 2013 he acquired a collection of horological papers which had been published by Nicholson. A little while after this, I must have popped into his in-box after finding his paper on Nicholson’s good friend John Hyacinth Magellan (1722-1790).

In this article, Jonathan Betts forensically examines the two clocks which have been signed by Nicholson, although – as we know that Nicholson employed instrument-makers – ‘it seems very likely that Nicholson oversaw the clock’s construction to his specification’ rather than having any ‘hands-on’ involvement,

Nicholson’s table regulator clock lives at the British Museum (and was highlighted in an earlier blog). Betts describes the design and combination of features in the movement of this clock as “unique” and “evidently designed so that the technical features can be exposed and appreciated – very much in line with Nicholson’s desire to disseminate technical information”.

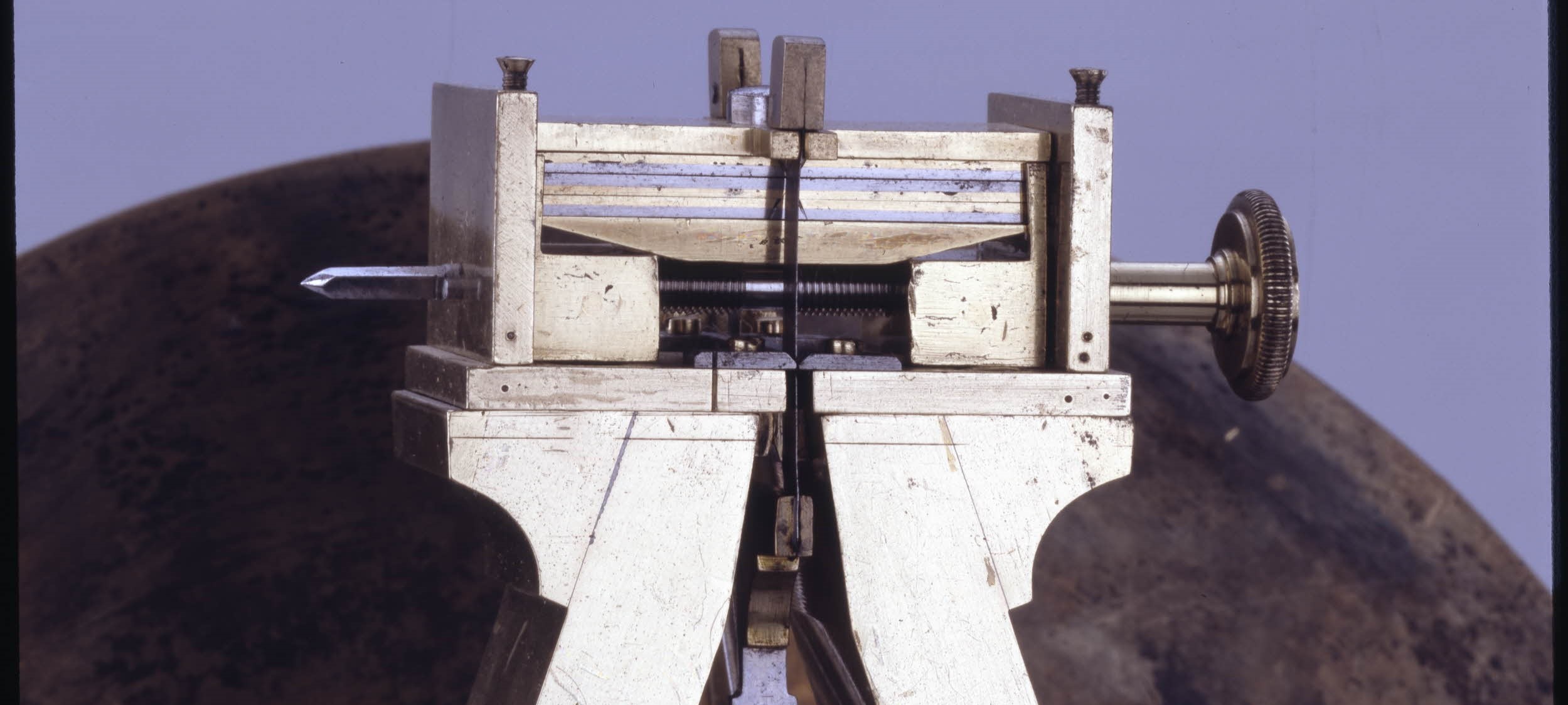

The second clock - featuring for the first time in public in the AHS Journal - is described as a ‘miniature gimballed regulator” with parts dated 1805 and 1806, and as “more elegant” and “even more exposed and ‘on show’”.

Unfortunately, Betts describes how this design had a ‘significant failing in the proportions of the dead-beat escapement’ which can lead to a stopping or bottoming, although this may have been prevented by the gimbal arrangement in the design.

A gimbal is a pivoted support that permits rotation of an object about an axis (for example, like a stabiliser on a hand-held camera), and it seems that this clock was ‘almost certainly mounted on a tripod and was thus intended to be used in a ‘portable’ environment’ for example, at sea or when surveying.

Could Nicholson have designed this for use this onsite at the West Middlesex Waterworks in late 1806?

To purchase Antiquarian Horology Volume 43

If you are interested in horology and the technical details of these two clocks, then it is possible to purchase a single issue of Antiquarian Horology Volume 43 via the AHS website Shop for just £8.50 plus P&P.

#41

If museum image fees are "killing art history” what hope for historians of science and commerce …

November 11th, 2017share this

Image Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay

Well done to the group of art historians who wrote to The Times on 6 November:

“The fees charged by the UK’s national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished. Such fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge that is the very purpose of public museums and galleries. Fees charged for academic use pose a serious threat to art history: a single lecture can cost hundreds of pounds; a book, thousands.”

A full copy of the letter (and more recent developments) can be found on the website www.arthistorynews.com.

As someone who uses images as a daily basis for marketing, I am used to being able to licence stock images (photographs or drawings) from websites such as Istockphoto or Shutterstock for a reasonable fee, and was shocked to find out how much some museums wished to charge, how complicated the fee structure can be, and how inconsistent the pricing structure is across various national institutions.

Initially, I had been keen to include a large number of illustrations in my modern biography of Nicholson - hoping to bring some potentially dry scientific subjects to life - but I soon had to modify my aspirations.

By way of example, when writing this blog on Nicholson’s clock, which is in the British Museum but not on public display, I was only allowed to include the three images provided by the Museum under the Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence, “an internationally recognised licence recommended by one of the Directives we are expected to follow as a public sector body.”

However, the museum did not have photographs of some interesting and unique aspects of the clock including a close up of the inscription “William Nicholson / 1797” and a side view showing the fusee mechanism.

While I was permitted to take photographs, and video, for my personal use during the visit – I was not allowed to use these on the blog, as

“… you can certainly use your own images for ‘private and non-commercial purposes’ but I’m afraid you are not permitted to publish these images.

This allows us to maintain the quality of representation of our objects, keep a record of what is used and avoid any complications regarding future copyright.

The Museum’s Visitor Regulations regarding personal photography is:

8. Film, photography and audio recording

8.1 Except where indicated by notices, you are permitted to use hand-held cameras (including mobile phones) with flash bulbs or flash units, and audio and film recording equipment not requiring a stand. You may use your photographs, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/2011-11-14%20Visitor%20Regulations%20FINAL.pdf

The image rights team kindly offered to “easily arrange new photography for £85 + VAT (30 day turnaround but often much faster)”. How they might incur such costs was a mystery to me, and I did not bother to ask whether this was per photograph.

This seems to go against the British Museum’s object of:

The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be FREELY accessible.

Given that Nicholson’s clock is not on public display, one might have thought they would see the benefit of some broader exposure online – at no cost to the public purse.

In thinking about what to include in book, I am faced with this pricing structure for scholarly and academic books:

Total combined print run and download units (prices per image ex-VAT):

Up to 500: £30

501 – 1,000: £40

1,001 – 2,000: £50

2,001 – 3,000: £60

My initial plan to include up to eight images, in order to properly detail the design and mechanics, would set me back £400 if the print run is between 1,000 and 2,000. Somehow, I doubt that Neil MacGregor has this problem when choosing his next set of 100 hundred objects.

There is a big difference between the commercial value in the photograph of Nicholson’s clock’s fusee and an iconic sculpture such as the Discobolus, of which the British Museum sells replicas for £2,500.

I should think that the trustees of the British Museum would have a better understanding than most of the fact that many niche historical books have only a limited customer base, but are nonetheless extremely valuable in terms of the spread of knowledge and understanding.

#17

Nicholson’s table regulator clock at the British Museum

March 3rd, 2017share this

Images copyright British Museum

The British Museum was founded in 1753, the year of William Nicholson’s birth. I have evidence of at least two of his visits to the museum. The first was as part of his research for the 1783 edition of A Critical Review of the Public Buildings, Statues, and Ornaments, in and About London and Westminster. Then in January 1790, Nicholson deposited the journals of the Count de Benyowsky with the museum for safekeeping. He might have been rather delighted to know that one of his own creations would end up there too.

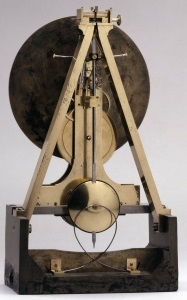

In 1958, one of Nicholson’s clocks was acquired by the British Museum as part of the Ilbert Collection - the most important collection of horology ever achieved by a private collector.

Courtenay Ilbert (1888-1956) was a civil engineer and he acquired the clock from a dealer called Clowes on 17 March 1938. He paid £20 for this 1797 regulator clock, a sum at the top end in comparison to the prices that Ilbert paid for other clocks from that period.

I recently enjoyed a visit behind the scenes with a curator of horology, Oliver Cooke, who had very kindly got the clock working for me. Previously I had seen the picture of the Nicholson’s clock on the British Museum website but had not registered the dimensions, and was surprised at how large it is.

Height: 57 centimetres

Width: 30.75 centimetres

Depth: 17.3 centimetres

The clock is described in David Thompson’s book Clocks as “an interesting example of a rather unassuming case which in reality conceals a movement of a most unusual and interesting design.”

The British Museum describes it as " SATINWOOD CASED EIGHT-DAY BRACKET TIMEPIECE WITH GRAVITY ESCAPEMENT AND CENTRE-SECONDS. Bracket timepiece; eight-day; gravity escapement; round silvered-metal dial with centre-seconds; satinwood case with moulded arched hood; glazed panels to front and sides surmounted by brass flaming vase finials. TRAIN-COUNT. Gt wheel 180" Click here for the full description.

The delicate mechanism for this 8-day clock rests upon a rather unprepossessing lump of steel which acts to stabilise the clock and to support the pendulum and the movement.

The plain steel pendulum rod would expand or contract with changes in temperature, but at the top Nicholson has built an ingenious mechanism with bi-metallic strips to compensate for the changes in temperature.

“Nicholson’s big solid design is going in the right direction – and it is good to see someone outside the clock-making tradition trying something different,” said Oliver Cooke. “It was clearly an attempt to make a precision timepiece, and you can see original thinking – even if Nicholson has not got it quite right.”

Nicholson’s name is engraved on the dial where the name of the commissioner/designer would usually appear: Wm Nicholson f 1797

More information can be found in:

Clocks by David Thompson, British Museum Press, London 2004.

Precision Pendulum Clocks, The Quest for Accurate Timekeeping, by Derek Roberts, Schiffer Pub Ltd, Atglen, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 2003

#4

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order