If museum image fees are "killing art history” what hope for historians of science and commerce …

November 11th, 2017share this

Image Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay

Well done to the group of art historians who wrote to The Times on 6 November:

“The fees charged by the UK’s national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished. Such fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge that is the very purpose of public museums and galleries. Fees charged for academic use pose a serious threat to art history: a single lecture can cost hundreds of pounds; a book, thousands.”

A full copy of the letter (and more recent developments) can be found on the website www.arthistorynews.com.

As someone who uses images as a daily basis for marketing, I am used to being able to licence stock images (photographs or drawings) from websites such as Istockphoto or Shutterstock for a reasonable fee, and was shocked to find out how much some museums wished to charge, how complicated the fee structure can be, and how inconsistent the pricing structure is across various national institutions.

Initially, I had been keen to include a large number of illustrations in my modern biography of Nicholson - hoping to bring some potentially dry scientific subjects to life - but I soon had to modify my aspirations.

By way of example, when writing this blog on Nicholson’s clock, which is in the British Museum but not on public display, I was only allowed to include the three images provided by the Museum under the Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence, “an internationally recognised licence recommended by one of the Directives we are expected to follow as a public sector body.”

However, the museum did not have photographs of some interesting and unique aspects of the clock including a close up of the inscription “William Nicholson / 1797” and a side view showing the fusee mechanism.

While I was permitted to take photographs, and video, for my personal use during the visit – I was not allowed to use these on the blog, as

“… you can certainly use your own images for ‘private and non-commercial purposes’ but I’m afraid you are not permitted to publish these images.

This allows us to maintain the quality of representation of our objects, keep a record of what is used and avoid any complications regarding future copyright.

The Museum’s Visitor Regulations regarding personal photography is:

8. Film, photography and audio recording

8.1 Except where indicated by notices, you are permitted to use hand-held cameras (including mobile phones) with flash bulbs or flash units, and audio and film recording equipment not requiring a stand. You may use your photographs, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/2011-11-14%20Visitor%20Regulations%20FINAL.pdf

The image rights team kindly offered to “easily arrange new photography for £85 + VAT (30 day turnaround but often much faster)”. How they might incur such costs was a mystery to me, and I did not bother to ask whether this was per photograph.

This seems to go against the British Museum’s object of:

The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be FREELY accessible.

Given that Nicholson’s clock is not on public display, one might have thought they would see the benefit of some broader exposure online – at no cost to the public purse.

In thinking about what to include in book, I am faced with this pricing structure for scholarly and academic books:

Total combined print run and download units (prices per image ex-VAT):

Up to 500: £30

501 – 1,000: £40

1,001 – 2,000: £50

2,001 – 3,000: £60

My initial plan to include up to eight images, in order to properly detail the design and mechanics, would set me back £400 if the print run is between 1,000 and 2,000. Somehow, I doubt that Neil MacGregor has this problem when choosing his next set of 100 hundred objects.

There is a big difference between the commercial value in the photograph of Nicholson’s clock’s fusee and an iconic sculpture such as the Discobolus, of which the British Museum sells replicas for £2,500.

I should think that the trustees of the British Museum would have a better understanding than most of the fact that many niche historical books have only a limited customer base, but are nonetheless extremely valuable in terms of the spread of knowledge and understanding.

#17

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787)

March 20th, 2017share this

In December 1780 in the Chapter Coffee House near St Paul's Cathedral, several men led by the Irish chemist Richard Kirwan decided to meet fortnightly to discuss ‘Natural Philosophy, in its most extensive signification’.

The membership of the group grew steadily, and meetings took place in a variety of locations including the Baptist’s Head Coffee House. William Nicholson joined in 1783 and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

Nicholson’s copy of the minutes of the society, until 1787 when it folded, are in Oxford’s Museum of the History of Science and it was wonderful to be able to inspect them recently.

Compared to other philosophical societies of that time, especially the Lunar Society which had been meeting in the Midlands since 1765, this group seems little known – partly because it never had any name.

In 1785 it was agreed that the group would have no formal name when Kirwan ‘affirmed that the society not being desirous of that kind of distinction which arises from name or title were so far from giving any sanction or authority to the names used by their secretaries that the original determination in this respect was that the society should not have a name.

Fortunately the minutes do include a most interesting list of 35 members (the total number of members over the life of the society was 55).

Mr Alex Aubert (1730-1805), Austin Friars, 26

MrWilliam Babbington(1756-1833)

MrAndrewBlackhall (?-?), Thavies Inn, Holborn

DrWilliamCleghorn(1754-1783), Haymarket, 11

DrJohnCooke(1756-1838)

DrAdairCrawford(1748-1795), Lambs Conduit Street, 48.

MrJean-Hyacinthde Magellan(1722-1790), Nevilles Court, 12

MajorValentineGardiner(1775-1803)

DrWilliamHamilton(1758-1807)

MrJamesHorsfall(-d1785), Inner Temple.

DrJohnHunter(c1754-1809), Leicester Square

DrCharlesHutton(1737-1823)

MrWilliamJones(1746-1794), Inner Temple

DrWilliamKeir(1752-1783), Adelphi

MrRichardKirwan(1735-1812), Newman Street, 11

DrWilliamLister(1756-1830)

MrPatrickMiller(1731-1815), Sackville Street, 17

MrEdwardNairne(1726-1806), Cornhill, 20

MrWilliam Nicholson(1753-1815)

DrGeorgePearson(1751-1828)

DrThomasPercival(1740-1804)

DrCharles William Quin(1755-1818), Harmarket, 11

DrJohnSims(1749-1831), Paternoster Row, 11

MrBenjaminVaughan(1751-1835), Mincing lane

MrAdamWalker(c1731-1821), George Street, Hannover Square

DrWilliam CharlesWells(1757-1817), Salisbury Court

MrJohnWhitehurst(1713-1788), Bolt Court, 4

DrJohnWatkinson(1742-1783), Crutched Friars, 22

Honorary members

DrMatthewBoulton(1728-1809), Birmingham

MrRichardBright(1754-1840), Bristol

MrJamesKeir(1735-1820), Birmingham

DrRichardPrice(1723-1791), Newington Green

Rev'd DrJosephPriestley(1733-1804), Birmingham

MrJamesWatt(1736-1819), Birmingham

MrJosiahWedgwood(1730-1795), Etruria

Further information

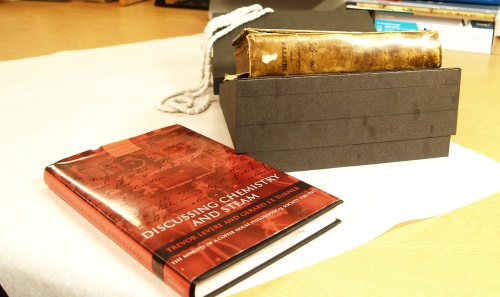

The entire set of minutes, as well as descriptions of all the members of the society, are set out in Discussing Chemistry and Steam: The Minutes of a Coffee House Philosophical Society 1780-1787, by Trevor H. Levere and Gerard L'E Turner.

Available from Oxford University Press

#5

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order