Eighteenth Century Mr Nicholson launches his YouTube Channel

December 15th, 2020share this

When William Nicholson launched his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts in 1979, part of his motivation was to speed up the transfer of scientific knowledge.

If he lived today, he would surely have embraced social media for that purpose - never lowering himself to insults or trolling!

Now he has added a Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account to his media channels, and we are able to share excerpts from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ a performance for the Bloomsbury Festival 2020 which took place in the open air of St George’s Gardens, London where Nicholson is buried.

Directed and introduced by Ian Brown, episode one is the historical part where his biographer Sue Durrell interviews Nicholson who has returned from his grave in the gardens to talk about his life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nicholson is brought to life most ably by actor Julian Date, who reminisces about his life at the crossroads of Georgian arts, literature, science, and commerce, and discusses the importance of his discovery in splitting water using Volta’s battery, alongside his friend Dr. Carlisle.

The short three excerpts in this video cover:

• Working for Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam and at the General Chamber of Manufacturers

• Nicholson’s motivation for launching his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts; and

• Remembering Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution and recalling the experiment with Anthony Carlisle where they split water into hydrogen and oxygen in May 1800.

This is the first of two videos from this event. Part two shows demonstrations of the experiment and discusses its implications in the quest for clean energy.

Julian Date is represented by Hilary Gagan Associates.

#36

Solving the C18th puzzle of scientific publishing

July 13th, 2020share this

A guest blog, by Anna Gielas, PhD

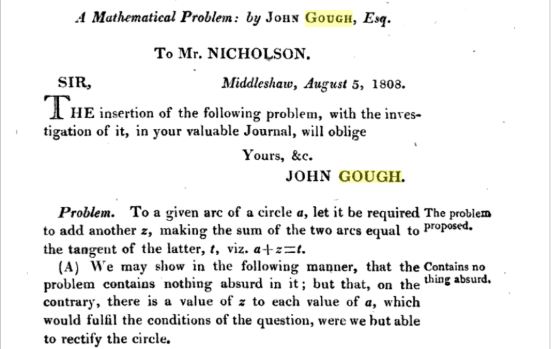

William Nicholson made Europe puzzle. Continental men of science translated and reprinted articles from his Journal on Natural Philosophy,Chemistry and the Arts on a regular basis—including the mathematical puzzles that Nicholson published in his column ‘Mathematical Correspondence’.

When Nicholson commenced his editorship in 1797, his periodical was one of numerous European journals dedicated to natural philosophy. Nicholson was continuing a trend that had existed on the continent for over a quarter of century. But at the same time, Nicholson was committing to a novel form of philosophical communication in Britain. The British periodicals dealing with philosophy and natural history were linked with learned societies. Besides the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, numerous philosophical societies in other British towns, including Manchester, Bath and Edinburgh, published their own periodicals. The London-based Linnaean Society, which had close ties to the Royal Society, also printed its transactions.

Nicholson’s editorship did not have any societal backing. He did not conduct his periodical in a group, but by himself. These circumstances made his Journal something different and novel—maybe even revolutionary. In the Preface to his first issue, Nicholson confronted the very limited circulation of society and academy-based transactions and their availability to the ‘extreme few who are so fortunate’. He made it his editorial priority to reprint philosophical observations from transactions and memoirs—to make them accessible to a wider audience.

Considering his friendship with the radical dramatist Thomas Holcroft and his collaboration with the political author William Godwin, we can think of Nicholson’s editorial priority in political terms: he wished to democratize philosophical communication. Personal experiences could have played a role here, too. Nicholson appears to have initially harbored some admiration for the Royal Society and its gentlemanly members. But he did not become a Fellow due to his social background. Whether he considered his inability to be part of the Society a social injustice is not clear. But this experience likely played a role in his decision to edit and reprint from society transactions.

There seems to be a political dimension to Nicholson’s editorship—yet the sources available today do not allow any straight-forward reading of the motives for his editorship. He did not present his editorship as a political move. Instead, he used the rhetoric of his contemporaries—the rhetoric of utility: ‘The leading character on which the selections of objects will be grounded is utility’, he wrote in his Preface. The Journal was supposed to be useful to ‘Philosophers and the Public’.

Nicholson had acquired the skills necessary for editing a periodical over many years. It seems that his organizing role in a number of societies and associations was particularly helpful to hone such abilities—for example, his membership at the Chapter Coffee House philosophical society. In mid-November 1784, Nicholson and the mineralogist William Babington were elected ‘first’ and ‘second’ secretaries of the society. During the gathering following his election, Nicholson appears to have raised 13 procedural matters for discussion and action. According to Trevor Levere and Gerard Turner, Nicholson ultimately ‘made the meetings much more effective and disciplined’.

His organizing role brought and kept him in touch with most of the Chapter Coffee House society members which enabled him to expand and affirm his own social circle among philosophers. So much so, that some of the society members would go on to contribute repeatedly to Nicholson’s Journal. As the ‘first’ secretary, Nicholson gained experience in steering a group of philosophers and experimenters towards a productive and lasting exchange—a task similar to editorship.

Nicholson was skilled in fostering and maintaining the infrastructure of philosophical exchange. His contemporaries were well aware of it and sought his support on a number of occasions. Among them was the publisher John Sewell who invited Nicholson to become a member of his Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Here, Nicholson and Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and Vice-President of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, had one of two conflicts.

Philosophical societies in late eighteenth-century London tended to have presidents and vice-presidents, committees and hierarchies. More often than not, these hierarchies mirrored the members' actual social ranks. As an editor, outside of a society, Nicholson was free from hierarchies. He could initiate and organize philosophical exchange as he saw fit—which likely made editorship attractive to him.

For Nicholson who was almost constantly in financial difficulties, editing was also a potential source of additional income. After all, the same month the first issue of his Journal came out, Nicholson's tenth child, Charlotte, was born. But the Journal did not become a commercial success. Yet, he continued it over years, until his health deteriorated. Non-material motives seem to have outweighed his monetary needs.

His journal was an integral part of Nicholson’s later life—particularly when he no longer merely reprinted pieces from exclusive transactions. After roughly three years since the first issue appeared, his Journal began to turn into a forum of lively philosophical discourse. In the issue from August 1806, for example, he informed his contributors and readers of the ‘great accession of Original Correspondence’, which he—whether for the reason of ‘utility’ or democratizing philosophy—published in later issues rather than foregoing publication of any of them.

Outside of Britain, the Journal was read in the German-speaking lands, Russia, Netherlands, Scandinavia, France and others. Nicholson made Europe puzzle indeed. He united geographically as well as culturally and socially distant individuals, bringing European men-of-science closer together.

Further reading:

Anna Gielas: Turning tradition into an instrument of research: The editorship of William Nicholson (1753–1815),

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1600-0498.12283

#29

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

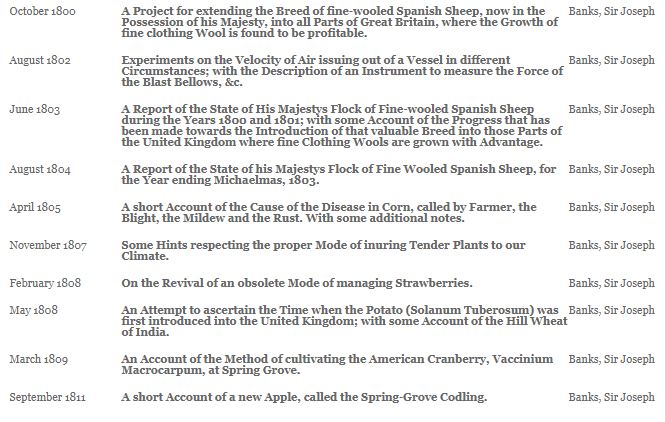

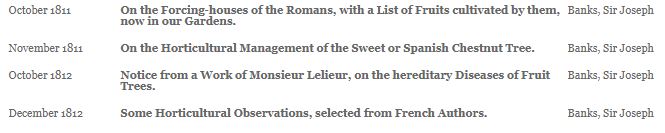

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order