'Experiments and Observations Made with Argand’s Patent Lamp,' - Shining a light on Nicholson's concentric wicks

July 18th, 2021share this

In The Collected Letters of Erasmus Darwin, edited by Desmond King-Hele, Letter 86-6 from Erasmus Darwin to Josiah Wedgwood, 21 April 1786, starts off “Sir, Mr Nicholson is an ingenious and accurate man …” and continues a series of discussions between the men about oil lamp designs, leading to the comment that “The pyramidical lamp would be more pleasing to they eye than the concentric one of Mr Nicholson.”

Having been searching for Nicholson’s 'concentric lamp' for many years, I was delighted to finally track it down in The London Magazine, of May 1785:

Experiments and Observations Made with Argand’s PatentLamp.

Sir

As the attention of the world has been much excited by the powerful effects of Argand’s Lamp, and as there are many who are desirous of making use of it provided its advantages were clearly ascertained, I presume the following description of the instrument and its effects will not be unacceptable to the public.

Yours, &C.

N.

The apparatus consists of two principal parts, a fountain to contain the oil, and the lamp itself. Of the former it is unnecessary to speak: the lamp is constructed as follows. The external parts consist of an upright metallic tube one inch and six-tenths in diameter, and three inches and a half in length, open at both ends. Within and concentric to this is fixed another tube of about one inch in diameter, and nearly of equal length; the space between these two tubes being left clear for the passage of air. The interior tube is closed at the bottom, and contains another similar tube a little more than half an inch in diameter. The third tube is soldered to the bottom of the second. It is perforated throughout so as to admit a current of air to pass through it, and the space between this tube and that which invirons it contains the oil. An ingenious apparatus, containing a piece of cotton cloth whose longitudinal threads are much the thickest, is adapted to nearly fill the space into which the oil flows. It is so contrived that the wick may be raised or depressed at pleasure. When the wick is considerably raised it is seen of a tubular form, and by the situation of the tubes already described is accessible to the air, both by means of the central perforation and the space between the exterior and second tube. When the wick is lighted, the flame is consequently in the form of a hollow cylinder, and is exceedingly brilliant. It is rendered somewhat more bright, and perfectly steady, by adapting a glass chimney whose dimensions are nearly the same with that of the exterior tube first described.

I hope this short description will be sufficient to convey an adequate idea of the instrument and shall therefore proceed to mention its effects. If the central hole be stopped, the flame changes from a cylindrical to a pyramidical form, becomes much less bright, and emits a considerable quantity of smoke. If the whole aperture be entirely or nearly stopped and the combustion becomes still more imperfect. The access of air to the external and internal surfaces of the flame is of so much importance, that a sensible difference is perceived when the hand or any other flat substance is held even at the distance of an inch from the lower aperture. There is a certain length of wick at which the effect of the lamp is the best. If the wick be too much depressed, the flame, though white and brilliant, is short; if it be raised, the flame becomes longer, and consequently the light more intense and vivid. A greater increase of the length, increases the quantity of the light, but at the same time the upper part of the flame assumes a brown hue, and smoke is emitted.

The lamp was filled with oil and weighed, it was then lighted and suffered to burn so as to produce the greatest quantity of light without smoke. After burning one hour and fifty-two minutes, it was extinguished and found to have lost 589 grains of its weight. Now a pint of oil weights 6520 grains and costs sixpence three farthings in retail; the lamp therefore consumes oil to the value of one penny in three hours. It remains to be shewn at what rate per hour the same quantity of light might be obtained from the tallow candles commonly used in families.

The candle called a middling fix, weighing upon an average the sixth part of a pound of avoirdupois, is 10¾ inches long, and 2 inches and 6/10 inch circumference. I have chosen to make my comparison with this candle as being, I imagine, most commonly used. It is to be understood that the lamp gave its maximum light without smoke.

The best method of comparing two lights with each other, that I know of, is this: Place the greater light at a considerable distance from a white paper, the less light may be moved nearer or father from the paper, accordingly as the experiment requires. If now an angular body, as the most convenient figure, be held before the paper it will project two shadows, these two shadows can coincide only in part, and their angular extremities will in all positions but one be at some distance from each other: the shadows being made to coincide in a certain part of their magnitude, they will be bordered with a lighter shadow, occasioned by the exclusion of the light from each of the two luminous bodies respectively. These lighter shadows in fact are spaces of the white paper illuminated by the different luminous bodies, and may with the greatest ease be compared together, because at a certain point they actually touch one another. If the space illuminated by the less light appear brightest, that light is to be removed farther off; and on the contrary, if it be the most obscure, that light must be brought nearer the paper. A considerable degree of precision may be obtained by this method of judging of lights, and by this method the following comparisons were made.

The candle was suffered to burn till it wanted snuffing so much, that large lumps of coaly matter were formed on the upper part of the wick. The candle then at the distance of 24 inches gave a light equal to that of the lamp at the distance of 129 inches: from this experiment it is deduced that the light of the lamp was equal to about 28 candles.

The candle was then snuffed, and it became necessary to remove it to the distance of 67 inches, before its light was so diminished as to equal that of the lamp at the before mentioned distance of 129 inches. From this experiment it is deduced that the light of the lamp was equal to not quitefour candles fresh snuffed.

Another trial with the lamp at the distance of 131 inches and a half, and another candle of the same size at the distance of 55 inches gave the lights equal. The candle was suffered to burn for some time, but did not seem to want snuffing, yet the light of the lamp then appeared to be stronger. The candle when newlysnuffed, the distances remaining the same, appeared rather to have the advantage of the lamp. These numbers give 5 2/3 candles for the light of the lamp, and I imagine the lamp to be rather better than this upon an average, because candles are suffered to go a much longer time without snuffing, and therefore in general give less lightthan was exhibited in these trials.

Another trial with the lamp raised so as to smoke a little, and the candle wanting snuffing, though the form of the wick had not yet begun to change, gave the proportion of the lamp to the candles at about 8 to 1. We may, therefore, I resume, take six middling fixes of tallow candles as an equivalent in light to the lamp. I tried the lamp against 4 candles lighted up together, placed on a distant table with the lamp, I retired till I could just discern the letters of a printed book by the light of the candles, the lamp being covered. I then directed my assistant to intercept the light of the candles and suffer the lamp to shine on the book; the lamp was the brightest. It seemed by trials of this kind to be rather better than five candles; but I was not at that time aware of the difference of the light of tallow candles, accordingly as they have been more or less recently snuffed, and as this method does not appear capable of that degree of exactness and facility the other possesses, I did not pursue it.

From these trials, it is evident that where light beyond a certain quantity is wanted, at a given place, these lamps must be highly advantageous; for the tallow candle being of six in a pound, and burning not quite seven hours, the lamp is equivalent to a pound of these candles lighted up for seven hours. Now, the expence of the lamp for seven hours is less than two pence halfpenny, and that of the candles eight pence; and if the proportion between wax and tallow candles be attended to, it will be seen that the advantages of this lamp for illuminating a theatre are very great.

The wax candles in Covent Garden Theatre are about eighty in number in the sconces, and by estimation may be worth about 2L sterling. An equal quantity of light would be afforded by fourteen of the patent lamps; for the candles used at the theatre do not give quite so much light as a tallow candle of six in a pound. The expence of the fourteen lamps for five hours will not exceed two shillings, according to the foregoing deduction.

Mr. Argand is certainly entitled to all the honour which his talents for philosophical combination have gained; and in the present instance, his claim as an inventor ought not to be disputed, though it should appear that the principle of his lamp was known and even applied to use long ago. Everyone is acquainted with the observation of Dr. Franklin, concerning the increase of light produced by joining the flames of two candles: and double candles have actually been made for, and used by shoemakers from time immemorial. The lamp of many wicks ranged in a right line, and used by watchmakers, gives a very great light for the same reason, namely because the flame being of no considerable thickness has access to air throughout and the combustion is perfectly maintained. Whereas in a thick flame the white heat or perfect ignition extends only to a certain distance from the exterior surface. This is exemplified in a striking manner in those large flames which issue from the chimnies of furnaces. These are luminous only to a certain distance inwards, and the interior part consists of vapour, hot indeed, but not on fire, so that If paper be held in the centre of the flame by means of an iron tube passed through the exterior burning part, the paper will not be set on fire. Mr. Argand has proposed the converting a right lined wick into a circular one; whether this be an advantage or no, except so far as concerns the convenience of having a longer range of conjoined flames within a less space I was desirous of ascertaining. The result of my trials are these.

I took one of Mr. Argand’s wicks, which when cut open longitudinally will form a line at the extremity proposed to be lighted, measuring about two inches and six-tenths. This wick was placed in a brass trough so that the upper edge of the wick was held perpendicular by the straight edge of the trough into which oil was put. The wick was then lighted, and it was easy to raise or lower it above the metallic edge at pleasure, because it adhered by means of the oil to the side of the brass vessel. I thus obtained a flame in a right line equal in length to the periphery of Argand’s flame, and as is the case in that lamp, I found it easy to lengthen or shorten the flame, to cause it to smoke or burn clear as has been before mentioned. The lamp and this right lined flame were placed near each other, and at the same height, the glass chimney being taken off the former: the flames of both were adjusted so as to emit a small quantity of smoke, and their lights tried. The experiment being made by means of the shadows, as before described, their lights proved exactlythe same: but to the eye, looking at both lamps together, the intensity of Argand’s flame appeared considerably the greatest; that is to say, it dazzled more and left a stronger impression when the organ of sight was directed to some other object.

Before I made this experiment I had some expectation, that the long flame would be preferable to the circular one, because I supposed the interior surface of the circular flame, could not throw out so much light as it would have done if it had been developed and exposed. I was even inclined to imagine that the greater part of the light of Argand’s lamp is furnished by the external surface of the flame. But the equality of the lights in the circular and the right-lined flames, shews that this opinion was ill founded, and that flame is in a very high degree transparent.

I therefore directed my attention to the shadow of a lighted candle, and observed, that when the candle does not smoke, the shadow is nearly the same as if the candle were not lighted; that is to say, as if there was no flame. But, if a piece of glass be held up in the same light, it will give a shadow sufficiently sensible: it therefore intercepts more of the light than flame does. This observation accounts for the superior brightness or dazzling of Argand’s lamp. For the light which falls on a given portion of the retina of the eye from Argand’s lamp is much more dense, because it consists not only of the light from the anterior but likewise from the posterior part of the flame.

My ideas on this subject were farther confirmed by an experiment I made with the two lamps; I placed the right-lined flame in such a direction that it should not, as it did before, shine on the paper by its broad side, but in the direction of its length; the comparison of its light with that of Argand’s lamp still exhibited equality. But the long flame was then much more dazzling and bright than that of Argand. This circumstance, which though highly curious, has not, as I know of, been before noticed, at least with that attention it deserves, may be applied to many valuable purposes; one in particular occurs to me that I cannot help mentioning. It should seem that anyproportion of light may be had for microscopic purposes, by means of a long flame placed in the direction of the axis of the illuminating lense.

I tried the transparency of this long flame, placed at right angles, to the ray of Argand’s lamp; it have no shadow; but when its length was placed in the direction of the ray, it gave a shadow bordered by two broad, well defined bright lines, which I have not yet sufficiently examined to be able to give any conjecture respecting them; thought they are undoubtedly owing to some optical deviation of the rays which pass in the vicinity or through the substance of the flame.

These observations on the transparency of flame suggest an improvement of which Argand’s lamp is susceptible. Instead of one ring of flame there may be two, three or more concentric rings, with air passages between them. The inner rings will shine through the outer with more facility than the presentflame does through the glass chimney; and it is probable that the rapidity of the current of air will be increased in a high proportion between these tubes of flame, so as to increase the vehemence and quantity of the ignition, and cause more light to be emitted than would answer to the mere increase of the line of wick.

P.S. Upon looking over this paper it occurred to me, that the singular fact of the same candle that gave only one twenty-eighth part of the light of the lamp, becoming so bright on being snuffed, as to give more than one fourth of the same light it was compared with (which is seven times as bright as before) might seem erroneous or founded in mistake. I have therefore, made several other experiments with snuffed and unsnuffed candles, and am well assured that a candle, newly snuffed, gives in general eight or even nine candles that have been suffered to burn undisturbed for an hour in a still place.

#39

Eighteenth Century Mr Nicholson launches his YouTube Channel

December 15th, 2020share this

When William Nicholson launched his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts in 1979, part of his motivation was to speed up the transfer of scientific knowledge.

If he lived today, he would surely have embraced social media for that purpose - never lowering himself to insults or trolling!

Now he has added a Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account to his media channels, and we are able to share excerpts from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ a performance for the Bloomsbury Festival 2020 which took place in the open air of St George’s Gardens, London where Nicholson is buried.

Directed and introduced by Ian Brown, episode one is the historical part where his biographer Sue Durrell interviews Nicholson who has returned from his grave in the gardens to talk about his life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nicholson is brought to life most ably by actor Julian Date, who reminisces about his life at the crossroads of Georgian arts, literature, science, and commerce, and discusses the importance of his discovery in splitting water using Volta’s battery, alongside his friend Dr. Carlisle.

The short three excerpts in this video cover:

• Working for Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam and at the General Chamber of Manufacturers

• Nicholson’s motivation for launching his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts; and

• Remembering Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution and recalling the experiment with Anthony Carlisle where they split water into hydrogen and oxygen in May 1800.

This is the first of two videos from this event. Part two shows demonstrations of the experiment and discusses its implications in the quest for clean energy.

Julian Date is represented by Hilary Gagan Associates.

#36

Mary Wollstonecraft, PPH and eighteenth century maternal care

November 26th, 2020share this

With all the fuss about the Mary Wollstonecraft statue, it reminded me that one of the topics which was on my mind was the state of maternity care at the end of the eighteenth century. William and Catherine Nicholson seemed to do pretty well with at least 10 kids making it to adulthood. (One infant death is recorded, one of the twelve children still remains a mystery).

Caitlin Moran’s response on Twitter to the statue in Newington Green was ‘If you want to make a naked statue that represents "every woman", in tribute to Wollstonecraft, make it e.g. a naked statue of Wollstonecraft dying, at 38, in childbirth, as so many women did back then - ending her revolutionary work. THAT would make me think, and cry.’{10 November 2020}

So, I turned to Lisetta Lovett, a retired consultant psychiatrist and medical historian, and asked whether this standard of maternal care was normal for the time? Or was Mary Wollstonecraft just particularly unlucky in her medical advisers?

The information which I had compiled on the birth of Mary’s baby with William Godwin was that:

Mary went into labour on Wednesday 30 August, choosing to hire a midwife but no nurse. Godwin described the role of the midwife ‘in the instance of a natural labour, to sit by and wait for the operations of nature, which seldom in these affairs demand the operation of art.’

Little Mary was born at 11.20pm and, sometime after 2.00am, Godwin who was keeping out of the way in the parlour, was informed that the placenta had not been removed. A physician was called for and he removed the placenta ‘in pieces’. The loss of blood was ‘considerable’ and Mary’s health did not improve over the next few days, despite a second doctor visiting and pronouncing that Mary was ‘doing extremely well’.

Godwin wrote that ‘On Monday, Dr Fordyce forbad the child having the breast, and we therefore procured puppies to draw off the milk.’

Then on Wednesday, following a recommendation by family friend Dr Carlisle, ‘it was now decided that the only chance of supporting her through what she had to suffer, was by supplying her rather freely with wine … I neither knew what was too much, nor what was too little. Having begun, I felt compelled under every disadvantage to go on. This lasted for three hours.’

Dr Fordyce was no beginner - see wikipedia - although we do not know if he was the attending doctor on the first two occasions. Dr Carlisle was a close family friend who went on to become the Surgeon Extraordinary to King George IV in 1820.

Lisetta, whose book Casanova's Guide to Medicine: 18th century Medical Practice is due to be published by Pen and Sword Ltd in April 2021, kindly provided the following insights into the medical profession and the little that we know about Mary Wollstonecraft’s death:

The information given here, taken from William Godwin’s diary as well as other sources, raises more questions than it answers. However, it looks like Mary suffered from a post-partum haemorrhage, the cause of which seems to have been a retained placenta.

The medical definition of a retained placenta is one that has not been expelled within 30 minutes of delivery. This is still a leading cause of maternal death worldwide, and treatment today is intervention with oxytocin either in the third stage of labour or after delivery and, if this fails, then manual removal under anaesthesia.

By the 19th century, obstetrics had become a medical specialty in its own right, much to the irritation of the midwives. Following the advent of man-midwives, medical doctors moved into the specialty. Neither Dr Fordyce or Dr Carlisle are recorded as having such expertise, but maybe this is not so surprising given that obstetrics as a medical specialty developed a little after their time.

There is a telling quote from a Dr Edgell in On Obstetric Practice, in 1816: "I believe it was an aphorism of the late Dr Clarke, that no woman should die of haemorrhage if an accoucheur is called early...".

Post-partum haemorrhage was a well recognised and potentially lethal complication of child-birth. Accoucheurs applied a variety of treatments to manage it and knew that a quick response could be life-saving. These treatments ranged from a hand in the uterus to stimulate contraction of the uterus and therefore expel the retained placenta (see Davis David in Principles and Practice of Obstetrics 1832-65) to the use of cold water on the stomach, or even injected in the rectum.

The obstetric literature of the early 19th century reveals that there was a lot of medical debate about what measures were most effective, including whether stimulants like brandy or wine should be administered. As the Covid pandemic illustrates, doctors are often in disagreement and so we should not be surprised.

Clearly, Mary would have been better off with an experienced accoucheur, medically trained or not, present throughout the birth ready to respond to any complications. The midwife at least knew that a retained placenta was bad news and informed Godwin who called for a physician. He tried to remove the placenta but probably did not do so completely; a difficult task without the benefit of an anaesthetic and a dreadful ordeal for Mary. For whatever reason, he did not continue to attend her which was a pity.

It is not clear if Mary continued to bleed or not but, given the second doctor's optimism, it sounds as if the bleeding appeared to have stopped.By the time Dr Fordyce is called, it is four days post-partum! He may have suggested the puppies in order to stimulate the uterus to contract and thereby encourage the expulsion of any remaining placenta as suckling induces the body to produce oxytocin. But why not allow the baby to suckle Mary?

Perhaps, she already had a wet nurse, and the doctor wanted to avoid disruption to the baby's feeding. That being said, the cult of breast-feeding your own baby had become popular in the 18th century especially in France where Rousseau’s re-evaluation of maternity was influential. Mary had spent several turbulent years living in France and was no doubt aware of this.

Mary obviously was deteriorating, in part because she continued to lose blood (perhaps internally so it was not obvious) leading to severe anaemia. She may have also developed septicaemia although there is no mention of her having a fever. Ironically, one cause of this could have been manual placental removal. At this time there was little, if no notion, of the importance of keeping one’s hands clean to prevent dissemination of germs.

When Carlisle finally sees her, I think he knows she is going to die and this is why he suggests wine as a 'tonic', not as a treatment but rather as an anaesthetic to make her last hours a little more bearable.

Godwin must have bitterly regretted his early laissez faire comment about childbirth. It is a great pity that he had not employed from the outset an experienced accoucheur, although even so Mary might have died. At this time, childbirth was one of the most dangerous challenges a woman might be obliged to address.

You can follow Lisetta Lovett on her blog Casanova's Medicine.

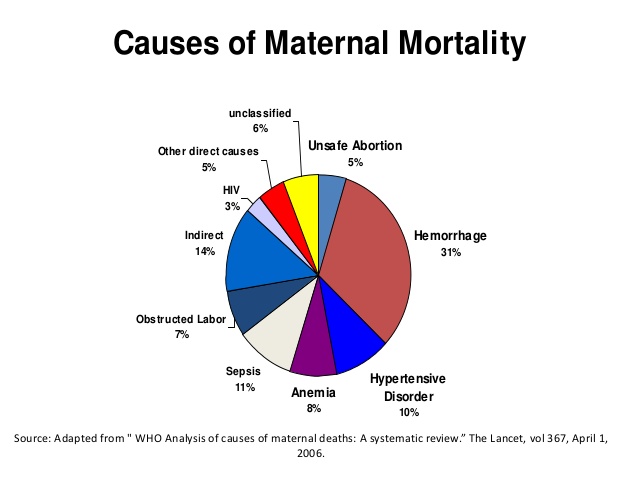

Today, according to the WHO, about 14 million women around the world suffer from postpartum haemorrhage every year. This severe bleeding after birth is the largest direct cause of maternal deaths. And of course, in addition to the suffering and loss of women’s lives, when women die inchildbirth, their babies also face a much greater risk of dying early. Shockingly, 99% of the deaths from PPH occur in low- and middle-income countries, compared with only 1% in high-income countries.

#35

17 and 20 October - In Conversation with William Nicholson and the UCL Ucell clean energy team at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival

August 28th, 2020share this

It is very exciting to announce that William Nicholson (1753-1815) will be making an appearance at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival alongside the UCL hydrogen fuel cell demonstrator!

Saturday 17 October 2020,

2.30 – 3.30 pm – Live event in St George’s Gardens, London, WC1N 6BN at thewest end.

Tickets £8 (£6 concs) – Clickhere for details.

Tuesday 20 October 2020

2.30 – 3.30pm – Online event, via the Bloomsbury Festival at Home

Tickets £5 – Clickhere for details.

How the discovery of electrolysis has changed the future’s energy landscape

August 25th, 2020share this

A guest blog by Alice Llewellyn from UCell, the electrochemical outreach group at UCL

Shortly after the invention of the battery in the form of a voltaic pile by Alessandro Volta in 1800, William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840) discovered that water can be split into its constituent elements (hydrogen and oxygen) by using electrical energy.This phenomena is termed electrolysis and is the process of using electricity to produce a chemical change. Electrolysis was a critical discovery, which shook the scientific community at the time. It directly demonstrated a relationship between electricity and chemical elements. This fact helped scientific legends – Faraday, Arrhenius, Otswald and van’t Hoff develop the basics of physical chemistry as we know them.

Fast forward to today, and we are faced with one of the greatest challenges – climate change. This effect has accelerated the search for alternative fuels and energy storage devices fin order to decarbonise the energy sector. Burning fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) for energy is the main cause of climate change as it produces carbon dioxide gas which leads to a greenhouse effect and the warming of our atmosphere.

A huge contender for alternative fuels is hydrogen. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe. However, it does not typically exist as itself in nature and is most commonly bonded to other molecules, such as oxygen in water (H2O). This is where electrolysis plays a key role. Electrolysis can be used to extract hydrogen from the compound which can then go on to be used as a fuel. Moreover, if a renewable source of energy is used (for example wind or solar) to provide the electricity required to split the water, then there is no carbon footprint associated with this hydrogen production.

Hydrogen can then be used in fuel cells to produce electricity. Fuel cells are electrochemical energy devices, they convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy without any combustion. The way in which a fuel cell works is in fact the reverse process of electrolysis. In a fuel cell, hydrogen is split into its protons and electrons which then react with oxygen to produce water, electricity and a little bit of heat. As the only side product of this reaction is water, fuel cells are a very clean way to produce electricity.

Energy from renewable sources (wind, solar…) is intrinsically intermittent. Depending on the season or time of the day more or less energy is produced. To make sure the supply of energy is secure and stable, energy needs to be stored when an excess is produced and later fed back into the grid when needed. Water electrolysis offers grid stabilization. When a surplus of energy is available, e.g. during the day when the sun is shining, some of this energy is used to produce hydrogen. This hydrogen can then easily be stored in tanks. Whenever more energy is needed, e.g. when it is dark, hydrogen is taken from tanks and fuelcells are used to release the energy stored in the hydrogen.

Not only can hydrogen be used for grid stabilisation, but this can also be used to transform the transport sector, which contributes to around a quarter of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions. Fuel cell vehicles are one of the solutions that have been adopted to tackle this problem and are classed as zero-emission vehicles (only water comes out of the exhaust).

In 2019, London adopted a fleet of hydrogen-powered double decker buses – a world first! As more people start to learn about this technology, more fuel cell vehicles can be spotted on our roads.

Without the discovery of electrolysis by Nicholson and Carlisle in 1800, it might not be possible to produce pure hydrogen for these applications in such an environmentally-friendly way, making the fight against climate change a more difficult task.

*

About our guest author Alice Llewellyn

Following a masters project synthesizing and testing novel battery negative electrodes, Alice Llewellyn, started her PhD project in the electrochemical innovation lab at UCL, primarily using X-ray diffraction to study atomic lattice changes in transition metal oxide cathodes during battery degradation. Alice co-runs the electrochemical outreach group UCell.

UCell is a group of PhD and masters students based at University College London, who are passionate about hydrogen, clean technologies and electricity storage and love sharing their knowledge and experience to the general public through outreach, taking their 3 kW fuel cell stack to power stages, thermal cameras and, well, anything that needs powering! In a time of a changing energy landscape, they aim to show how these technologies are starting to become a regular feature in our everyday lives.

#30

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

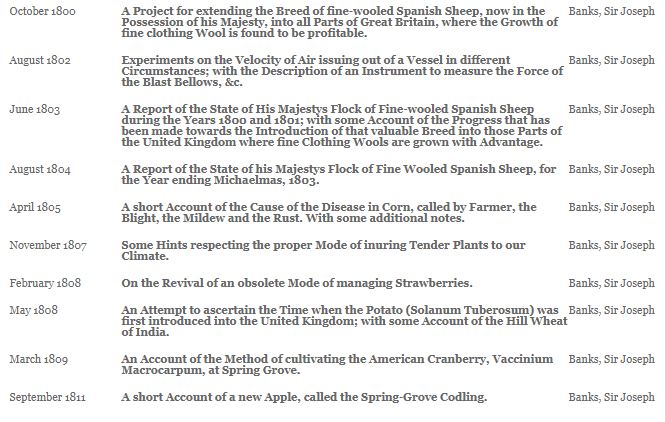

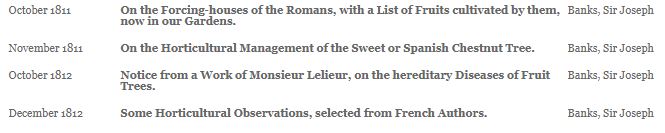

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

Invention #1 - Nicholson’s Hydrometer

January 15th, 2018share this

A hydrometer is a device for measuring a density (weight per unit volume) or specific gravity (weight per unit volume compared with water). It was also called an aerometer, a gravimeter or a densimeter.

On 1 June 1784, Nicholson wrote to his good friend Mr. J. H. Magellan with: ‘A description of a new instrument for measuring the specific gravities of bodies’.

According to Museo Galileo, hydrometers date back to Archimedes and the Alexandrian teacher Hypatia, but the second half of the nineteenth century saw the design of several types which were well-used in industry of which “the better-known models include those developed by Antoine Baumé (1728-1804) and William Nicholson (1753-1815)”.

Nicholson’s paper, which does not seem to be accompanied by a drawing, was published the following year in the Memoirs of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (London: Warrington, 1785) 370–380, and can be accessed via Google Books

In the first edition of Nicholson’s A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, Nicholson wrote an article about the hydrometers invented by Baumé – one for spirits and one for salts - which had never been used in this country, but never mentioned his own earlier invention.

In June 1797, Nicholson published a translation of a paper that had been read in France at the National Institute by Citizen Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveau (1737-1816), and then published in the Annales de Chimie. Nicholson points out that ‘this translation is nearly verbal’ as he finds himself writing about his own invention.

Comparing Nicholson’s hydrometer with that designed by Fahrenheit which he described as ‘not fit for the hand of the philosopher’, Guyton de Morveau says:

“The form which Nicholson gave some years ago to the hydrometer of Fahrenheit, rendered it proper to measure the density of solids. At present it is very much used. It gives, with considerable accuracy, the ratio of specific gravity to the fifth decimal,water being taken as unity. … It does not appear that any better instrument need be wished for in this respect.”

Of all of Nicholson’s inventions, this one still bears his name and is called Nicholson’s hydrometer today. Examples can be found in several museums, and it is possible to purchase a modern version for use in school experiments for just a few dollars.

The Oxford Museum of the History of Science kindly showed me their Nicholson’s hydrometer from 1790.

Others can be found at:

HarvardUniversity Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

St.Mary's College in Notre Dame, Indiana

The VirtualMuseum of the History of Mineralogy (Private collection)

Sadly, I couldn’t find a video online with a demonstration of Nicholson's hydrometer being used. If anyone knows of one, or feels the urge to produce one, I would love to share it on this website.

#20

FutureLearn MOOC - Humphry Davy: Laughing gas, literature and the lamp.

October 4th, 2017share this

A MOOC (for those of you like me who did not know what this was) is a ‘massive open online course’, and Lancaster University and the Royal Institution of Great Britain are hosting one about Humphry Davy which will start on 30 October 2017.

The course will run for four weeks. Learners will typically spend three hours per week working through the steps, which will include videos (filmed on location at the Royal Institution), text-based activities and discussion, and quizzes. Learners will be guided at all stages by a specialist team of educators and mentors. It's entirely free to participate, and no prior knowledge of Davy is required.

Humphry Davy was a good friend of William Nicholson and they were both keen disseminators of knowledge, so would encourage you to spread the word to anyone who might be interested.

In 1797 young Davy had ‘commenced in earnest his study of natural philosophy,’ but this ‘soon gave place to that of chemistry’ and in his note book he recorded that his first experiments ‘were made when I had studied chemistry only four months, when I had never seen a single experiment executed, and when all my information was derived from Nicholson’s Chemistry, and Lavoisier’s Elements.’ (style='"Times New Roman",serif;' (Davy and Davy, The Collected Works,1839.)

Then in the Spring of 1799, Davy made contact with Nicholson sending two articles to include in A Journal of Natural Philosophy and the Arts, both of which appeared in the May edition:

- Experiments and Observations on the Silex composing the Epidermis or external Bank, and contained in other Parts of certain Vegetables.

- Introductory to the Experiments contained the subsequent Article, and on other Subjects relative to the Progress of Science.

There is much more to tell about their relationship, but now is not the time, so let’s get back to the MOOC …

This FREE course is intended for anyone with an interest in Humphry Davy, or early nineteenth century literature, science, or history. It will explore some of the most significant moments of Davy's life and career, including his childhood in Cornwall, his work at the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol and the Royal Institution in London, his writing of poetry, his invention of his miners' safety lamp and the controversy surrounding this, and his European travels. The course will also investigate the relationships that can exist between science and the arts, identify the role that science can play in society, and assess the cultural and political function of science.

Free course – open to all - sign up today at

http://www.futurelearn.com/courses/humphry-davy

#14

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal 334,799

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order