Publication update: Is this the closest I will get to appearing alongside Liam Neeson?

December 17th, 2017share this

OK, that got the ladies’ attention …!

I have been so busy checking facts, dates and references that, with my brain firmly in the eighteenth century, I forgot to update the website with our publication plans.

Firstly, I am delighted to say that I was signed up by PeterOwen Publishers, one of the leading independents. I was the last non-fiction writer to besigned before Peter Owen passed away at the grand age of 89. He established his publishing house in 1951 and accumulated a record-breaking ten Nobel prize-winners over sixty-five years in business.

Miraculously, they were the first publishing house that I approached but, like those of you who know Nicholson already, they instantly recognised that our hero was in need of a biography.

In Peter Owen’s obituary in the Telegraph, he was described as ‘bewilderingly eclectic’ and a ‘champion of the obscure’ – given that Nicholson and I are little known (for now), that seems like a pretty good fit. I shall enjoy being obscure in good company.

The Life of William Nicholson was written 150 years ago and until now, has been available only to historians via a visit to the Bodleian Museum (MSS. Don. d. 175, e. 125), but it is now available to order online and will be in shops in the new year.

So, what has this got to do with Liam Neeson? Well I couldn’t help being just a little thrilled to see his brooding presence either side of Mr Nicholson on the cover of Nobel prizewinner Silence by Shusaku Endo (a recent film by Martin Scorsese).

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

I was too late on the scene to be invited to the film premier, but maybe Liam Neeson could be tempted to audition for the role of Irish chemist Richard Kirwan, founder of the philosophical coffee society?

Just don’t mention that there isn’t a movie (yet)!

#18

If museum image fees are "killing art history” what hope for historians of science and commerce …

November 11th, 2017share this

Image Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay

Well done to the group of art historians who wrote to The Times on 6 November:

“The fees charged by the UK’s national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished. Such fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge that is the very purpose of public museums and galleries. Fees charged for academic use pose a serious threat to art history: a single lecture can cost hundreds of pounds; a book, thousands.”

A full copy of the letter (and more recent developments) can be found on the website www.arthistorynews.com.

As someone who uses images as a daily basis for marketing, I am used to being able to licence stock images (photographs or drawings) from websites such as Istockphoto or Shutterstock for a reasonable fee, and was shocked to find out how much some museums wished to charge, how complicated the fee structure can be, and how inconsistent the pricing structure is across various national institutions.

Initially, I had been keen to include a large number of illustrations in my modern biography of Nicholson - hoping to bring some potentially dry scientific subjects to life - but I soon had to modify my aspirations.

By way of example, when writing this blog on Nicholson’s clock, which is in the British Museum but not on public display, I was only allowed to include the three images provided by the Museum under the Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence, “an internationally recognised licence recommended by one of the Directives we are expected to follow as a public sector body.”

However, the museum did not have photographs of some interesting and unique aspects of the clock including a close up of the inscription “William Nicholson / 1797” and a side view showing the fusee mechanism.

While I was permitted to take photographs, and video, for my personal use during the visit – I was not allowed to use these on the blog, as

“… you can certainly use your own images for ‘private and non-commercial purposes’ but I’m afraid you are not permitted to publish these images.

This allows us to maintain the quality of representation of our objects, keep a record of what is used and avoid any complications regarding future copyright.

The Museum’s Visitor Regulations regarding personal photography is:

8. Film, photography and audio recording

8.1 Except where indicated by notices, you are permitted to use hand-held cameras (including mobile phones) with flash bulbs or flash units, and audio and film recording equipment not requiring a stand. You may use your photographs, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/2011-11-14%20Visitor%20Regulations%20FINAL.pdf

The image rights team kindly offered to “easily arrange new photography for £85 + VAT (30 day turnaround but often much faster)”. How they might incur such costs was a mystery to me, and I did not bother to ask whether this was per photograph.

This seems to go against the British Museum’s object of:

The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be FREELY accessible.

Given that Nicholson’s clock is not on public display, one might have thought they would see the benefit of some broader exposure online – at no cost to the public purse.

In thinking about what to include in book, I am faced with this pricing structure for scholarly and academic books:

Total combined print run and download units (prices per image ex-VAT):

Up to 500: £30

501 – 1,000: £40

1,001 – 2,000: £50

2,001 – 3,000: £60

My initial plan to include up to eight images, in order to properly detail the design and mechanics, would set me back £400 if the print run is between 1,000 and 2,000. Somehow, I doubt that Neil MacGregor has this problem when choosing his next set of 100 hundred objects.

There is a big difference between the commercial value in the photograph of Nicholson’s clock’s fusee and an iconic sculpture such as the Discobolus, of which the British Museum sells replicas for £2,500.

I should think that the trustees of the British Museum would have a better understanding than most of the fact that many niche historical books have only a limited customer base, but are nonetheless extremely valuable in terms of the spread of knowledge and understanding.

#17

Book Review – A walk on part in ‘The Shape of Water’

October 22nd, 2017share this

As the marketing guru John Hegarty said (and I am fond of quoting) “Do interesting things, and interesting things will happen to you” – and how true this has been. Little did I know where my first visit to the Wedgwood Museum would lead … to Tasmania.

William and Catherine Nicholson’s daughter Mary (1787 - 1807/8) married a Captain with the East India Company, Hugh Macintosh (1775 - 1834) at Fort St George, in Madras, India. Sadly, she died very shortly after giving birth to William Hugh Mackintosh (1807-1840) in December 1807.

Hugh Macintosh eventually travelled to Van Diemen‘s Land (now Tasmania) where, in partnership with Peter Degraves, he was one of the founders of The Cascade Brewery Company in 1824.

Back in the summer 2016, I received an email from the author Anne Blythe Cooper in Tasmania in regard to this connection. As it was the middle of the day, and the time difference seemed favourable, I decided to give her a ring – only to find that she was in Yorkshire.

The subject of interest for Anne was Sophia (the wife of Peter Degraves), about whom little was known. Like the women in Nicholson’s life, and many at that time, so little was recording in writing that they are almost invisible today.

Anne was also planning a trip to Anglesey, which meant that she would be almost passing Staffordshire. Seizing the opportunity, we arranged to meet and spent many hours trying to fill plug holes in the histories of the Degraves and Macintosh/Nicholson family connections.

In The Shape of Water: Imagined fragments from an elusive life: Sophia Degraves of Van Diemen's Land, a work of historical fiction, Anne Blythe-Cooper tells the fascinating story of the life, hardships, imprisonments and eventual success of the Degraves family through the eyes of Sophia.

Knowing very little of the history of the Van Diemen's Land, renamed as Tasmania in 1856, I found it a fascinating read. The descriptions of the societal, entrepreneurial and environmental conditions are very vivid, and it was delightful to read William and Mary Nicholson’s first appearances in a work of historic fiction (as far as I am aware).

I was interested to learn of the Tasmanian tiger (sadly declared extinct in 1936) and Mount Wellington, the development of the brewery and the theatre. Peter Degraves, sounds like a nightmare of a husband – but that certainly makes the book an enjoyable read.

So far it is only available via Forty South Publishing in Tasmania, but as the early story is set in London and many of the characters have English heritage – it deserves to be published in the UK too.

For now, it can be ordered via via Forty South Publishing - The Shape of Water by Anne Blythe-Cooper.

#16

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

FutureLearn MOOC - Humphry Davy: Laughing gas, literature and the lamp.

October 4th, 2017share this

A MOOC (for those of you like me who did not know what this was) is a ‘massive open online course’, and Lancaster University and the Royal Institution of Great Britain are hosting one about Humphry Davy which will start on 30 October 2017.

The course will run for four weeks. Learners will typically spend three hours per week working through the steps, which will include videos (filmed on location at the Royal Institution), text-based activities and discussion, and quizzes. Learners will be guided at all stages by a specialist team of educators and mentors. It's entirely free to participate, and no prior knowledge of Davy is required.

Humphry Davy was a good friend of William Nicholson and they were both keen disseminators of knowledge, so would encourage you to spread the word to anyone who might be interested.

In 1797 young Davy had ‘commenced in earnest his study of natural philosophy,’ but this ‘soon gave place to that of chemistry’ and in his note book he recorded that his first experiments ‘were made when I had studied chemistry only four months, when I had never seen a single experiment executed, and when all my information was derived from Nicholson’s Chemistry, and Lavoisier’s Elements.’ (style='"Times New Roman",serif;' (Davy and Davy, The Collected Works,1839.)

Then in the Spring of 1799, Davy made contact with Nicholson sending two articles to include in A Journal of Natural Philosophy and the Arts, both of which appeared in the May edition:

- Experiments and Observations on the Silex composing the Epidermis or external Bank, and contained in other Parts of certain Vegetables.

- Introductory to the Experiments contained the subsequent Article, and on other Subjects relative to the Progress of Science.

There is much more to tell about their relationship, but now is not the time, so let’s get back to the MOOC …

This FREE course is intended for anyone with an interest in Humphry Davy, or early nineteenth century literature, science, or history. It will explore some of the most significant moments of Davy's life and career, including his childhood in Cornwall, his work at the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol and the Royal Institution in London, his writing of poetry, his invention of his miners' safety lamp and the controversy surrounding this, and his European travels. The course will also investigate the relationships that can exist between science and the arts, identify the role that science can play in society, and assess the cultural and political function of science.

Free course – open to all - sign up today at

http://www.futurelearn.com/courses/humphry-davy

#14

Change time at the Royal Exchange

September 27th, 2017share this

Image: The Royal Exchange, London c1750, Courtesy of Wikigallery

The following sentence in The life of William Nicholson by his Son caused me to Google ‘Change Time’ to see what this referred to:

‘And daily congregated in the shop after change time six or eight or more of the leading merchants to gossip over politics and the affairs of the day …’

Rather amusingly, an explanation came up from our very own Mr Nicholson in The British Encyclopedia, 6 vols of 1809, which I thought worthy of sharing due to the severity of the punishments threatened:

In 1703, the following notice appeared in the public papers: "An act of the Lord Mayor and Court of Alder men is affixed at the Exchange, and other places in this City, by which all persons are prohibited coming upon the Royal Exchange to do business before the hours of twelve o'clock, and after the hour of two, till evening change: Wherein it is further enacted, that for a quarter of an hour before twelve the Exchange bell shall ring, as a signal of change time ; and shall also begin to ring a quarter of an hour before two, at which time the change shall end : and all persons shall quit it, upon pain of being prosecuted to the utmost, according to law. That the gates shall then be shut up, and continue so till evening change time; which shall be from the hours of six to eight from Lady-day till Michaelmas, and from Michaelmas to Lady-day from the hours of four to six; before and after which hours the bell shall ring as above said. And it is further enacted, that no persons shall assemble in companies, as stock jobbers, &c. either in Exchange Alley, or places adjacent, to stop up and hinder the passage from and to the respective houses thereabouts, under pain of being immediately carried before the Lord Mayor, or other Justice of the Peace, and prosecuted."

For an explanation of Lady Day, click here

For an explanation of Michaelmas, click here.

#13

Holcroft, Nicholson and the C18th gig economy

September 3rd, 2017share this

While the phrase ‘gig economy’ has been all over the mainstream media recently with the publication of the Good Work: The Taylor Review of modern working practices, the expression has been around for nearly a decade and insecure working arrangements have been around for centuries. In 2015, The Financial Times chose the expression for its FT 2015 Year in a Word, by Leslie Hook.

Leslie traced the expression back to the height of the financial crisis in 2009, ‘when the unemployed made a living by gigging, or working several part-time jobs, wherever they could’ with the word ‘gig’ emanating from jazz club musicians in the 1920s.

I could not help noting the similarities with life for many in the 18th Century as I re-read the Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft by William Hazlitt. Holcroft was a good friend of Nicholson, and his early employment history included time as a shoemaker, a stable lad at Newmarket, and as a chorister where he earned the nickname ‘the sweet singer of Israel’.

Holcroft headed for London where, like many young people today, he ‘felt the effects of poverty very severely’ and ruminated on what might have resulted from a good education. He was getting so desperate for work that he was heading to the office which recruited soldiers for the East India Company when he bumped into a friend who mentioned an opportunity with a travelling theatre company in Dublin. Then, for several years, he traipsed about the country in search of one opportunity after another before finally settling in London as a writer and dramatist.

Nicholson too was no stranger to the gig economy, having first worked for Josiah Wedgwood on a 'consultancy assignment' to Amsterdam to investigate financial irregularities with the Dutch sales agency. This had led to an employed position in Amsterdam, but only for a discrete project and so Nicholson had to return to London in search of work.

When young William Nicholson came to lodge with Holcroft at Southampton Buildings in around 1780, Holcroft subcontracted bits of writing to him. He also tried to persuade Nicholson that ‘at least as much revenue could be obtained from literary publications, as from any of the objects … of his thoughts.’

Over 25 years, Nicholson successfully built a steady income from writing, translating and publishing. But, with a large family to feed, he also took several gigs on the side. Projects included consulting on technical issues, sometimes as an early patent agent, acting as Secretary to the Chapter Coffee House Society and the General Chamber of Manufacturers. Then in the mid-1800s, he took on assignments as a civil engineer for a couple of water supply projects.

Unfortunately, like many who operate in the gig economy today, Holcroft and Nicholson did not set aside enough of their incomes during the good times to provide for ill-health in their old age.

The gig economy is not such a new phenomenon, but it does remind us that workers did not always enjoy the social safety nets that we often take for granted and are comparatively recent developments in the history of employment:

•1908 – old age pension introduced for men over 70

•1938 – paid holiday introduced

•1940 – old age pensions introduced for women

•1948 - the NHS was introduced.

#12

World Helicopter Day – On Aerial Navigation

August 20th, 2017share this

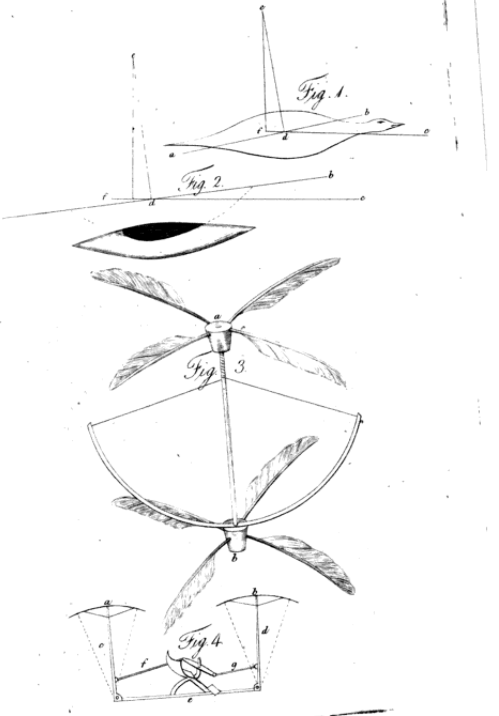

I have just noticed that 20 August is World Helicopter Day, and on a recent visit to the helicopter museum in Weston-Super-Mare (the World's Largest Dedicated Helicopter Museum) with my father, a former helicopter engineer, I spotted a reference to the three papers by Sir George Cayley in Nicholson’s Journal.

‘On Aerial Navigation’ was published in three parts:

Nicholson’s Journal, November 1809

Nicholson’s Journal, February and March 1810

I have since seen this described online, by Mississippi State University, as:

"Arguably the most important paper in the invention of the airplane is a triple paper On Aerial Navigation by Sir George Cayley. The article appeared in three issues of Nicholson's Journal. In this paper, Cayley argues against the ornithopter model and outlines a fixed-wing aircraft that incorporates a separate system for propulsion and a tail to assist in the control of the airplane. Both ideas were crucial breakthroughs necessary to break out of the ornithopter tradition."

This sketch from the November 1809 paper.

If any historians of aeronautic developments would like tocontribute a guest blog on the significance of Cayley’s papers, please email us at

info@nicholsonsjournal.com.

#12

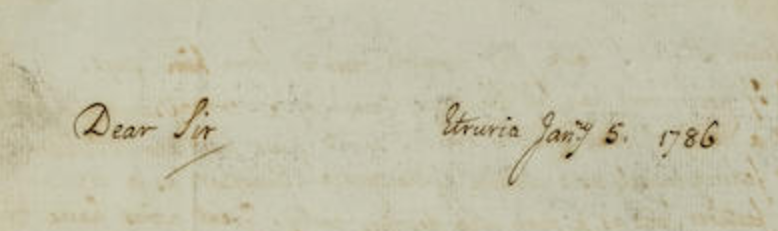

Josiah Wedgwood’s advice on international trade negotiations …January 1786

August 3rd, 2017share this

When Josiah Wedgwood was invited to chair the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he remembered the able young man who had served him well in the Netherlands in the 1770s, and invited William Nicholson to serve as his secretary.

International trade was a fundamental concern of the Chamber, as it is today, and it was interesting to come across this letter online which had been auctioned by Bonham’s in 2004.

Wedgwood wrote to the Rt Hon William Eden who was about to depart to France to negotiate a trade treaty, with this simple request:

“With regard to our particular manufacture, we only wish for a fair and simple reciprocity, and I suppose (but I speak without any authority) that our Manchester & Birmingham friends would be willing to give & take in the same way...”

http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11288/lot/144/?page_lots=8&upcoming_past=Past

#11

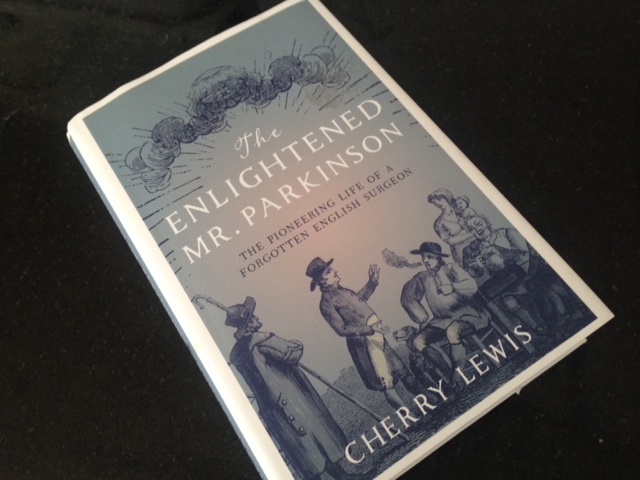

Book review: The Enlightened Mr Parkinson

July 28th, 2017share this

As we near publication of the Life of William Nicholson by his son, I find myself scanning the shelves of every bookshop to see whether much, if any, space is given to Georgian biographies. I was delighted to come across this biography in prime position on the New Releases shelf: THE ENLIGHTENED MR. PARKINSON – The pioneering life of a forgotten English surgeon by Cherry Lewis.

Parkinson identified a specific type of shaking palsy and it is this mental health condition for which his name is recognised today, but the biography tells a broader story of his work in general medical practice, his involvement in social and political reform, and his interest in fossils and geology. He was one of the founders of the Geological Society in 1807.

I particularly enjoyed the way that the author has explained the background at a time of tumultuous and constant change occasioned by wars, political upheaval, societal advances, medical and scientific discoveries. This is done in a very accessible way which ensures that the book will be just as enjoyable for a reader who is not intimate with that period of his life, between 1755 and 1824.

Parkinson’s life coincided pretty well with William Nicholson (1753-1815). They would certainly have met at the Geological Society, which Nicholson joined on the suggestion of their mutual friend Anthony Carlisle, if not in the mid-1790s when Parkinson was a member of the London Corresponding Society with Nicholson’s good friend Thomas Holcroft.

Parkinson submitted four papers to Nicholson’s Journal:

October 1807 - Nondescript Encrinus, in Mr. Donovans Museum.

March 1809 - On the Existence of Animal Matter in Mineral Substances.

May 1809 - On the Dissimilarity between the Creatures of the present and former World, and on the Fossil Alcyonia.

January and February 1812 - Observations on some of the Strata in the Neighbourhood of London, and on the Fossil remains contained in them.

THE ENLIGHTENED MR. PARKINSON – The pioneering life of a forgotten English surgeon

By Cherry Lewis, published by ICON

http://www.iconbooks.com/ib-title/the-enlightened-mr-parkinson/

#10

2017 Hull & 1804 a 'Half-mad' story of South Sea Whaling

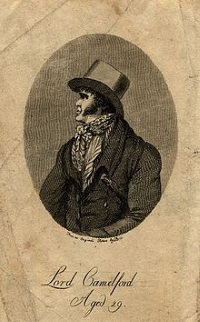

May 1st, 2017share this

Image: Robert Salmon [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The second interesting discovery via the Hull Maritime Museum was sparked by their display of the history of whaling. Although the whalers departing from Hull headed mainly for the Arctic Waters, there was some mention of the south sea fisheries, and I was pointed towards a most useful resource: the British Southern Whale Fishery (BSWF) Database.

Run by the University of Hull, the online database supplies details of actual voyages, and the people involved in the BSWF between 1775 and 1859.

The British southern whale fishery, commenced in 1775 and its trade was almost exclusively carried out from London. Initially it focused primarily in the mid to south Atlantic; by the mid-1790s it had moved to the Pacific and Indian Oceans and was limited to the areas off the coasts of Africa, South America and the east coast of Australia, but by 1815 the trade had spread to the wider Pacific.

The trade was often referred to as the South Seas Whale Fishery, and it was some unfortunate project related to this with Thomas Pitt, Baron Camelford II, (the Half-Mad Lord) which was at the root of Nicholson’s financial problems in later life.

Camelford’s project involved an investment in two whaling ships, believed to be called the Experiment and the Wilding which were secured by a ‘reputable merchant’ called Mr Rogers.

The Wilding is listed on the database; it sailed in 1803 and returned in 1805 under the command of John Borlinder.

Unfortunately, there are a number of vessels called the Experiment, but none of these sailed in the southern seas around 1804, the year in which Camelford was shot in a duel and died.

If you can contribute any information on the Experiment or the Wilding, Mr Rogers or John Borlinder, or their connection with homas Pitt, Baron Camelford II, please get it touch: info@nicholsonsjournal.com.

#7

2017 Hull City of Culture / 1777 Wedgwood Shipping

April 13th, 2017share this

Imagecourtesy of MyLearning.org © Hull Museums

Our son is working in Hull, so with it being Hull’s year as the City of Culture we decided to tread the tourist trail on a recent visit and enjoyed a tour of the Maritime Museum.

I am always struck by how busy sea ports appeared in paintings from the seventeenth and eighteenth century and this image of Hull’s first port particularly caught my eye. It was built between 1775 and 1778, creating the largest port in Britain. The dates rang a bell as I knew that Wedgwood was shipping his pottery to Amsterdam from Hull just the year before.

In May 1777, Nicholson was working as Josiah Wedgwood’s agent in Holland where he was responsible for negotiating the transfer of the pottery business to Lambertus van Veldhuysen. Nicholson wrote to Thomas Bentley on 20 June 1777 that van Veldhuysen:

‘expects all future orders to be expeditiously forwarded & shipped at Hull at the charge of Mr Wedgwood, or at London when haste is required.’

Van Veldhuysen’s agent in Hull was Thomas Horwarth.

1777 was also the year that the Trent and Mersey canal was completed, allowing Wedgwood to convey his pottery to Hull via the waterways and thereby reduce the number of breakages.

By 1783, over 13 million pieces of pottery and earthenware were being exported via Hull (not all Wedgwood).

#6

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787)

March 20th, 2017share this

In December 1780 in the Chapter Coffee House near St Paul's Cathedral, several men led by the Irish chemist Richard Kirwan decided to meet fortnightly to discuss ‘Natural Philosophy, in its most extensive signification’.

The membership of the group grew steadily, and meetings took place in a variety of locations including the Baptist’s Head Coffee House. William Nicholson joined in 1783 and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

Nicholson’s copy of the minutes of the society, until 1787 when it folded, are in Oxford’s Museum of the History of Science and it was wonderful to be able to inspect them recently.

Compared to other philosophical societies of that time, especially the Lunar Society which had been meeting in the Midlands since 1765, this group seems little known – partly because it never had any name.

In 1785 it was agreed that the group would have no formal name when Kirwan ‘affirmed that the society not being desirous of that kind of distinction which arises from name or title were so far from giving any sanction or authority to the names used by their secretaries that the original determination in this respect was that the society should not have a name.

Fortunately the minutes do include a most interesting list of 35 members (the total number of members over the life of the society was 55).

Mr Alex Aubert (1730-1805), Austin Friars, 26

MrWilliam Babbington(1756-1833)

MrAndrewBlackhall (?-?), Thavies Inn, Holborn

DrWilliamCleghorn(1754-1783), Haymarket, 11

DrJohnCooke(1756-1838)

DrAdairCrawford(1748-1795), Lambs Conduit Street, 48.

MrJean-Hyacinthde Magellan(1722-1790), Nevilles Court, 12

MajorValentineGardiner(1775-1803)

DrWilliamHamilton(1758-1807)

MrJamesHorsfall(-d1785), Inner Temple.

DrJohnHunter(c1754-1809), Leicester Square

DrCharlesHutton(1737-1823)

MrWilliamJones(1746-1794), Inner Temple

DrWilliamKeir(1752-1783), Adelphi

MrRichardKirwan(1735-1812), Newman Street, 11

DrWilliamLister(1756-1830)

MrPatrickMiller(1731-1815), Sackville Street, 17

MrEdwardNairne(1726-1806), Cornhill, 20

MrWilliam Nicholson(1753-1815)

DrGeorgePearson(1751-1828)

DrThomasPercival(1740-1804)

DrCharles William Quin(1755-1818), Harmarket, 11

DrJohnSims(1749-1831), Paternoster Row, 11

MrBenjaminVaughan(1751-1835), Mincing lane

MrAdamWalker(c1731-1821), George Street, Hannover Square

DrWilliam CharlesWells(1757-1817), Salisbury Court

MrJohnWhitehurst(1713-1788), Bolt Court, 4

DrJohnWatkinson(1742-1783), Crutched Friars, 22

Honorary members

DrMatthewBoulton(1728-1809), Birmingham

MrRichardBright(1754-1840), Bristol

MrJamesKeir(1735-1820), Birmingham

DrRichardPrice(1723-1791), Newington Green

Rev'd DrJosephPriestley(1733-1804), Birmingham

MrJamesWatt(1736-1819), Birmingham

MrJosiahWedgwood(1730-1795), Etruria

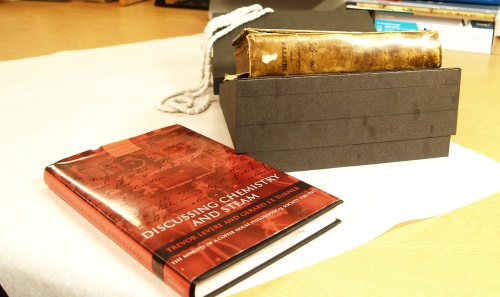

Further information

The entire set of minutes, as well as descriptions of all the members of the society, are set out in Discussing Chemistry and Steam: The Minutes of a Coffee House Philosophical Society 1780-1787, by Trevor H. Levere and Gerard L'E Turner.

Available from Oxford University Press

#5

Nicholson’s table regulator clock at the British Museum

March 3rd, 2017share this

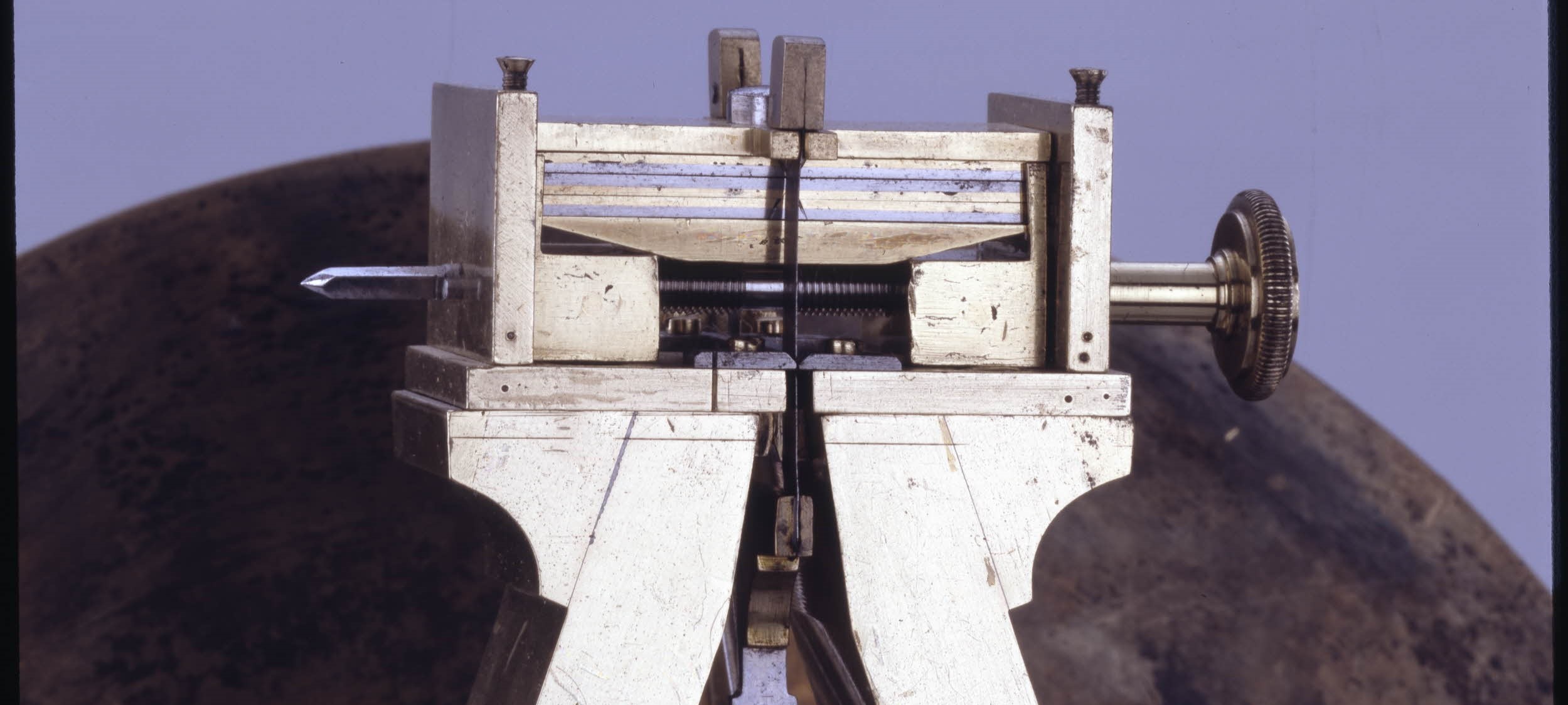

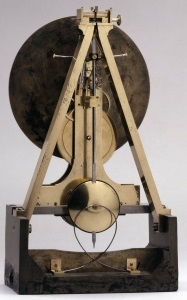

Images copyright British Museum

The British Museum was founded in 1753, the year of William Nicholson’s birth. I have evidence of at least two of his visits to the museum. The first was as part of his research for the 1783 edition of A Critical Review of the Public Buildings, Statues, and Ornaments, in and About London and Westminster. Then in January 1790, Nicholson deposited the journals of the Count de Benyowsky with the museum for safekeeping. He might have been rather delighted to know that one of his own creations would end up there too.

In 1958, one of Nicholson’s clocks was acquired by the British Museum as part of the Ilbert Collection - the most important collection of horology ever achieved by a private collector.

Courtenay Ilbert (1888-1956) was a civil engineer and he acquired the clock from a dealer called Clowes on 17 March 1938. He paid £20 for this 1797 regulator clock, a sum at the top end in comparison to the prices that Ilbert paid for other clocks from that period.

I recently enjoyed a visit behind the scenes with a curator of horology, Oliver Cooke, who had very kindly got the clock working for me. Previously I had seen the picture of the Nicholson’s clock on the British Museum website but had not registered the dimensions, and was surprised at how large it is.

Height: 57 centimetres

Width: 30.75 centimetres

Depth: 17.3 centimetres

The clock is described in David Thompson’s book Clocks as “an interesting example of a rather unassuming case which in reality conceals a movement of a most unusual and interesting design.”

The British Museum describes it as " SATINWOOD CASED EIGHT-DAY BRACKET TIMEPIECE WITH GRAVITY ESCAPEMENT AND CENTRE-SECONDS. Bracket timepiece; eight-day; gravity escapement; round silvered-metal dial with centre-seconds; satinwood case with moulded arched hood; glazed panels to front and sides surmounted by brass flaming vase finials. TRAIN-COUNT. Gt wheel 180" Click here for the full description.

The delicate mechanism for this 8-day clock rests upon a rather unprepossessing lump of steel which acts to stabilise the clock and to support the pendulum and the movement.

The plain steel pendulum rod would expand or contract with changes in temperature, but at the top Nicholson has built an ingenious mechanism with bi-metallic strips to compensate for the changes in temperature.

“Nicholson’s big solid design is going in the right direction – and it is good to see someone outside the clock-making tradition trying something different,” said Oliver Cooke. “It was clearly an attempt to make a precision timepiece, and you can see original thinking – even if Nicholson has not got it quite right.”

Nicholson’s name is engraved on the dial where the name of the commissioner/designer would usually appear: Wm Nicholson f 1797

More information can be found in:

Clocks by David Thompson, British Museum Press, London 2004.

Precision Pendulum Clocks, The Quest for Accurate Timekeeping, by Derek Roberts, Schiffer Pub Ltd, Atglen, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 2003

#4

‘Count Rumford called but seldom’

February 10th, 2017share this

Who would be the equivalent today of the American physicist Sir Benjamin Thomson, Count Rumford, FRS (1753-1814)?

A quick review of the current fellows of the Royal Society, filtered by the scientific area of ’physics’ and a free text search for a ‘Sir’ brings up the engineer Lord Broers – an expert in nanotechnology and former Chairman of the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee.

He sounds rather important, and if he was calling round to see my father (rather than summoning my father to a meeting at his own convenience), I might think the fact was worth recording in some detail.

Frustratingly, William Nicholson’s son and biographer leaves us with nothing more than that short phrase ‘Count Rumford called but seldom’ in his memoir of his father The Life of William Nicholson (1753-1815).

There is no hint to the object of their discussions – although they might have related to Nicholson’s work on the Committee of Chemistry at the Royal Institution.

From the perspective of young William, Count Rumford was just one of many estimable visitors who worked with his father in various societies, attended Nicholson’s scientific lectures or weekly conversazione, or consulted him on patents or matters of civil engineering.

With the names of his father’s associates including the likes of Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, Richard Kirwan, Sir Joseph Banks, Humphry Davy, Frederick Accum, Richard Trevithick, Jabez Hornblower, Jean-Hyacinth Magellan and Anthony Carlisle, one can see how young William might have become blasé about one more 'important' visitor.

#3

STEM for girls - and how this biography might never have been started

February 3rd, 2017share this

Wedgwood-Museum-in-Barlaston-pic-by-Tom-Pennington-under-creative-commons

One of the questions that I am most frequently asked is how on earth I happened to be writing a book about an eighteenth-century scientist.

Colleagues tend not to be surprised that I am writing a book, as I have always written and published a great deal as part of my career in marketing. But friends and family who have known me since my school days will have witnessed a fundamental aversion to science, particularly biology (too gory) and chemistry (too smelly). I remember my science teacher as being very kind and patient, but cutting open worms and frogs and foul-stinking experiments could never capture my imagination. I hope the S in STEM is more inspiring these days.

On the other hand, history and languages had me in thrall. How could you not want to set sail with the explorers? Or imagine the thrill of inventing the steam engine or designing the first iron bridge and seeing it built? How wonderful to design an intricate piece of pottery and for it to come out of the kiln just as you had planned. I have always maintained an interest in industrial heritage and volunteered with the charity Arts & Business to help two industrial museums in the early 1990s, one of which was the Gladstone Pottery.

Luckily, my very first encounter with Nicholson was in my teens when my grandfather showed me the log book from Nicholson’s voyage to China on the Gatton in 1771. It was like having my own Marco Polo in the family.

This fact was buried deep in the recesses of my mind until around 2009 when I remembered Nicholson and his connection with Josiah Wedgwood, prompted by the Museum winning the Art Fund Prize as Museum of the Year and the financial failure of the Wedgwood business being much in the news. As this was all less than ten miles from my home, it seemed sensible to see if there might be any evidence of Nicholson’s employment by Wedgwood before the collection was dispersed – as was threatened at the time.

Sadly, I could find no employment contract or even payslips – but there was a wealth of correspondence between Nicholson and Josiah Wedgwood or his partner Thomas Bentley in regards to affairs of the agency in Amsterdam. Then later, between 1785 and 1787 Nicholson was secretary to Wedgwood at the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain (about which I will write another day).

I need to confess that it was some time before I learnt of Nicholson’s scientific works, and if my first encounter had been with anything to do with chemistry I would have backed right off.

But finding a direct connection to one of the heroes of marketing (Wedgwood is known as a father of modern marketing) and a major player in the industrial revolution - I was hooked and needed to know more.

#2

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order