Summer reading: Special offer for members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association

September 30th, 2018share this

The following article was first published in the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association newsletter on 15 August 2018.

‘I used to write a page or two perhaps in half a year, and I remember laughing heartily at the celebrated experimentalist Nicholson who told me that in twenty years he had written as much as would make three hundred Octavo volumes.’

William Hazlitt, 1821

This year has seen numerous celebrations of Mary Shelley’s ‘foundational work in science fiction’, but where did Mary Shelley learn about electricity?

Historians often trace this knowledge to a copy of Humphry Davy’s Elements of Chemical Philosophy which was published in 1816 – but many years before this, the child Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin had access to scientific instruments at 10 Soho Square with her playmates – the five daughters of William Nicholson (1753-1815).

The scientist and publisher William Nicholson was one of her father’s closest friends. In his diary, William Godwin records more than 500 meetings with Nicholson and his family between November 1788 and February 1810. Aside from their mutual friend the dramatist Thomas Holcroft (1,435 mentions) and direct family members, only a handful of other acquaintances are mentioned more frequently in Godwin’s diary.

Nicholson had opened a Scientific and Classical School at his home in Soho Square in 1800. It was here in the Spring that, with Anthony Carlisle, he famously decomposed water into hydrogen and oxygen using the process now called electrolysis.

Electrical experiments had long been an interest of Nicholson who had two papers on the subject read to the Royal Society by Sir Joseph Banks in 1788 and 1789.

In those days, science - or natural philosophy as it was called - was also a leisure activity. Scientific instruments were the latest toys for the affluent and experiments provided entertainment. One after-dinner game was The Electric Kiss: where young men would attempt to kiss a young lady who had been charged with a high level of static electricity. Sadly, the kisses were rarely obtained as, on approaching the young lady, the men would be jolted away by an electric shock.

In a house full of several children, and a dozen energetic students, Mary witnessed and is likely to have participated in experiments and pranks with the air pump or Nicholson’s revolving doubler – his invention of 1788 with which you could create a continuous electrical charge.

Despite his circle of literary friends, Nicholson is better known among historians of science for A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts which ran between 1797 and 1813 and was the first monthly scientific journal in Britain. It revolutionised the speed at which scientific information could spread - in the same way that social media has done more recently - and the Godwin family no doubt received copies.

Full sets of Nicholson’s Journal, as it was commonly known, are rare. Certain editions are particularly sought after, such as those which include George Cayley’s three papers on the invention of the aeroplane.

But Nicholson’s first success as an author was fifteen years previously with his Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782. This was the same year that he wrote the prelude to Holcroft’s play Duplicity.

Nicholson quickly abandoned writing for the theatre, but he never abandoned his literary friends with their anti-establishment views, and his body of work is more extensive than the voluminous scientific translations and chemical dictionaries for which he is best known – some of which change hands for thousands of pounds.

Other works included a six-day walking tour of London, a book on navigation – based on Nicholson’s experiences as a young man with the East India Company – and translations of the exotic biographies of the Indian Sultan Hyder Ali Khan and the Hungarianadventurer Count Maurice de Benyowsky. Nicholson also contributed short biographies for John Aikin’s General Biography series; he launched The General Review which ran for just six months in 1806; and heproduced a six-part encyclopedia.

Before Nicholson came to London, he had spent a period working for the potter Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam. Wedgwood held young Nicholson in high regard, commenting in 1777 that ‘I have not the least doubt of Mr Nicholson's integrity and honour’. Then in 1785, when Wedgwood was Chairman of the recently established General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he appointed Nicholson as secretary. In this role, Nicholson produced several papers on commercial issues including on the proposed IrishTreaty and on laws relating to the production and export of wool.

Towards the end of his life, Nicholson put his technical knowledge to work as a patent agent and later as a civil engineer, consulting on water supply projects in West London and Portsmouth. The latter project faced stiff competition from another local water company and, in 1810, Nicholson published A Letter to the Incorporated Company of Proprietors of the Portsea-Island Water-Works.

As William Hazlitt indicated, in the opening quotation, Nicholson’s works were extensive. His activities were varied and there is much in his writings that will be of interest to historians of literature, commerce and inventions, as well as to historians of science and the Enlightenment.

A full list of Nicholson’s publications can be found in The Life of William Nicholson, by his Son, which was first published by Peter Owen Publishers earlier this year (£13.99). The original manuscript, written 150 years ago in 1868, is held at the Bodleian Library.

Free postage and packing is offered to members of the ABA when purchasing direct from www.PeterOwen.com. Simply use the Coupon code ‘1753-1815’ in the shopping cart before proceeding to checkout.

#25

The Enlightenment Flyfishers (first published in Flyfishers' Journal)

July 12th, 2018share this

'Angling - Preparing for Sport': published in 'British Field Sports' in 1831, this copper-engraved print depicts the kind of fishing tackle and clothing which would have been familiar to Sir Humphry Davy's literary characters Halieus, Ornither, Poietes and Physicus.

Salmononia: or Days of Fly Fishing, first published in 1809 by the Cornish chemist and inventor Humphry Davy (1778-1829), is one of the most collectable of angling books from the early nineteenth century. It was dedicated to the Irish physician and mineralogist, William Babington, a longstanding friend of Davy and a fellow founder of the Geological Society of London in 1807.

The book, written while Davy was ill, takes the form of a series of discussions between four imaginary characters: Halieus, the accomplished fly fisher; Ornither, a county gentleman who has done a little fishing; Poietes, a fly-fishing nature-lover; and Physicus a natural philosopher who has never fished.

John Davy, in his Memoirs of the Life of Humphry Davy, paints a wonderful picture of his brother on the river:

"I am sorry I have not a portrait of him in his best days in his angler’s attire. It was not unoriginal, and considerably picturesque – a white, low-crowned hat with a broad brim; its under surface green, as a protection from the sun, garnished, after a few hours’ fishing, with various flies of which trial had been made, as was usually the case; a jacket either grey or green, single-breasted, furnished with numerous large and small pockets for holding his angling gear; high boots, water-proof, for wading, or more commonly laced shoes; and breeches and gaiters, with caps to the knees made of old hat, for the purpose of defence in kneeling by the river side, when he wished to approach near without being seen by the fish; such was his attire, with rod in hand, and pannier on back, if not followed by a servant, as he commonly was, carrying the latter and a landing net."

Humphry Davy admits that Salmononia was inspired by ‘recollections of real conversations with friends’ and John’s memoir revealed that Halieus was inspired by William Babington. But whose conversations inspired the other characters?

Two friends of both Davy and Babington that must be strong contenders are William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840). They are best known for their decomposition of water into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis, achieved in 1800 with a copy of Alessandro Volta’s recently invented pile – a discovery which so excited Davy that he wrote that: ‘An immense field of investigation seems opened by this discovery: may it be pursued so as to acquaint us with some of the laws of life!’

Davy met Nicholson when he arrived in London, having already corresponded and sent his first scientific papers to him in 1799 for publication in A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first monthly scientific publication in Britain, running between April 1797 and December 1813. Over the course of its life, Nicholson’s Journal included some twenty articles on fish (but not specifically fly fishing). The most important was the editor’s own in the article on the torpedo fish in 1797, which speculated about the source of the electric charge within the pelicules of the torpedo, and which inspired Volta to try the various combinations of discs (an important hint) resulting in the development of his battery pile. When Davy was appointed as Director of the Royal Institution, aCommittee for Chemical Investigation and Analysis was established, on which Nicholson was invited to participate.

Nicholson had known Babington since 1784 when they were joint secretaries of a philosophical coffee house society established by Richard Kirwan, another Irish chemist and geologist. He also knew Carlisle, then at Westminster hospital, through his close friend the radical author William Godwin whose wife Mary Wollstonecraft was attended by the surgeon before she died in 1797.

Unfortunately, we don’t have an account of Davy, Babington, Carlisle and Nicholson fishing together, but it is a scene that we might easily imagine.

Nicholson, who was a prolific publisher, in his 1809 British Encyclopedia, or Dictionary of Arts and Sciencesdescribes fly fishing as ‘an art of so much nicety, that to give any just idea of it, we must devote an article to it.’ Sadly, he does not write about fly-fishing as eloquently as he does about chemistry, simply describing a number of flies and his only advice on how to fish is ‘keep as far from the water’s edge as may be, and fish down the stream with the sun at your back, the line must not touch the water.’

But, in a memoir of The Life of William Nicholson, the manuscript of which has finally been published 150 years after it was written, there is a charming account by Nicholson’s son of fishing trips with Carlisle in around 1803:

"Carlisle was at that time about thirty years of age, good looking and active …

Having passed his early days at Durham and in Yorkshire, Carlisle was fond of the country and country sports. We had many a day’s fishing at Carshalton, where his intimacy with the Reynolds and Shipleys procured him the use of part of the stream where the public were excluded. He was a skilful fly fisher and during the day I generally carried the pannier and landing net, but towards night when the mills stopped, and the water ran over a bye-wash, I with my bag of worms and rod managed to hook some fish as big as were taken during the day.

We also had fishing grounds at a place in Hertford called Chenis which was rented as I understood by Carlisle and a fellow sportsman called Mainwaring. These two gentlemen and myself as a third in a post-chaise used to start at 6.00 o’clock am, breakfast at Ware or Hoddesdon and forward to the fishing, which was fine for a boy of fourteen. And then Mr Mainwaring always took a fowling piece with him and occasionally shot a bird which was worth all the fish, rods and lines and all.

Chenis was a remarkably quiet rural place and the little inn we slept at was situated in a settlement of some half dozen cottages and houses, but what its name was I do not know. On one occasion when our companion was called away Carlisle and I remained there for a day or two. We were very successful in our fishing and were about to depart when it turned out there was a county election going forward and there was no conveyance to be had for love or money. Carlisle was wanted at home and we had no choice but to start on foot, so away we went after breakfast with a boy to show us a footpath way through fields to Rickmansworth where we hoped to get some conveyance to London.

Carlisle had the best share of the luggage and the boy and I the remainder. The country we travelled was beautifully undulated and of a dry sandy soil. It was very hot and I suspect I was the first to feel fatigue. After a long trudge we stopped at a gate leading into a sandy lane and looking back at the hillside I was amazed at the display of poppies in full bloom, the whole field was a mass of crimson, a new sight to me.

I was very thirsty and tired and have often thought of that field and Burns’ immortal lines:

Pleasures are like poppies spread;

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

or like the snow fall on the river.

a moment white then melts forever.[1]

But time, like a pitiless master, cried onward and we had to trudge again. At last our guide left us on the dusty high road to Rickmansworth, where in time we arrived. Here we got some refreshment and awaited til a return post-chaise conveyed us to London. We had walked nearly 30 miles and it was my first walking adventure of any magnitude."

The story was written when young Nicholson was eighty, and his geography seems a bit muddled – I have been unable to locate a place called Chenis, in Hertford – but records exist for one in Buckinghamshire in the 1770s. Could he mean the river Chess if he was near Ware and Hoddesdon? The Chess also passes near a village called Chenies just a few miles from Rickmansworth. (If any readers of the Flyfishers’ Journal can help, I would be very interested to hear from them.)

Carlisle went on to enjoy a stellar medical career, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1804, where he became Professor of Anatomy 1808 to 1824.

In 1809, he published an account of some experiments into how fish swam, by cutting various fins off seven fish each of dace (cyprinus leusiscus), roach (cyprinus rutilus), gudgeon (cyprinus gobio) and minnow (cyprinus phoxinus). He recorded how, on removal of the pectoral fin [2] its progressive motion was not at all impeded, but it was difficult for the fish to ascend; on removing the abdominal fin as well, the fish could not ascend; on removing the single fins, ‘produced an evident tendency to turn around, and the pectoral fins were kept constantly extended to obviate that motion; … and so on, until all fins had been removed from the seventh fish which cruelly ‘remained almost without motion’.

Carlisle was appointed Surgeon Extraordinary in 1820 to King George IV and was knighted in 1821. He died in 1840, never losing his love of fishing.

"Sir Anthony Carlisle had been called into the Prince Regent mainly to consult as to what wine he should drink. Having ascertained that brown sherry was the favourite of the day, he recommended it and gave great satisfaction.

Carlisle wrote to me, while I was engaged in a survey in Yorkshire, to find him a handy honest unsophisticated lad as a servant. I did my best and sent him one. The lad turned out a stupid dog, but when I visited London a short time afterwards and dined with Carlisle this boy waited and amused me by incessantly answering Carlisle ‘Yes Sir Anthony, … no Sir Anthony’ and ‘Sir Anthony’ at the beginning, middle and end of every sentence. All this passed as a matter of course and reminded me how calmly we bear our dignities when they fall upon us.

Carlisle was a true fisherman and a great admirer of honest Izaak Walton and used to quote from that delightful book The Compleat Angler, so that when any food or wine was better than common he said ‘it was only fit for anglers or very honest men’; and then he had another joke when we got thoroughly wet on our fishing excursions, saying ‘it was a discovery, how to wash your feet without taking off your stockings’."

#24

[1] From Robert Burns, ‘Tam o’ Shanter’, Edinburgh Magazine, Mar 1791.

[2] All these articles can be found by searching the index.

Thomas Holcroft – Landlord and long-time friend (part 1)

May 9th, 2018share this

Towards the end of the 1770s, after returning to London from his work for Wedgwood in Amsterdam, William Nicholson took lodgings with the writer Thomas Holcroft and was introduced to his landlord’s colourful circle of friends. A fellow lodger was Elizabeth Kemble whose father had established a strolling theatre company, and whose sister Sarah Siddons was a well-known actress.

From their rooms in Southampton Buildings at the top of London’s Chancery Lane, Holcroft and Nicholson often headed down to ‘Porridge Island’ a small row of cook-shops near to St Martins-in-the-Field where they enjoyed a nine-penny dinner and met up with other writers and musicians.

According to his son, Nicholson wrote a great deal for Holcroft who was used to having an amanuensis. The first piece of work to which Nicholson is know to have contributed was a novel published in 1780 entitled Alwyn: or The Gentleman Comedian. William Hazlitt, who completed Holcroft’s memoir (with assistance from Nicholson) explained how ‘it was originally intended that N.... should compile from materials to be furnished by Holcroft, but of which he in fact only wrote a few short letters, evidently very much against the grain.’

The second piece of work, which was attributed to Nicholson, was the prologue to a drama called Duplicity. The play opened in October 1781 at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, and the prologue was performed by Mr Lee-Lewes.

The opening performance was met with great applause and positive reviews. Holcroft described his feelings as ‘having escaped from the Dog of Hell, the Elysian fields are before me, if I have but taste and prudence to select the sweets.’ One can imagine the celebrations in Southampton Buildings that night and the excitement of Nicholson and his new bride as they mingled with the cast which included Elizabeth Inchbald, another renowned actress.

Unfortunately, within just a few days, Duplicity failed to generate enough revenue to cover the expenses of the house and Mr Harris of the Theatre Royal declared that ‘unless it was commanded by the King, he should not think of playing it any more’.

Nicholson’s son claimed that his father continued to produce ‘essays, poems and light literature for the periodicals of the day’ while working with Holcroft, but frustratingly for us ‘to none of which he put his name’.

A couple of years later, after war with France had ended, Holcroft made his name with the unscrupulous infringement of another playwright’s intellectual property. Having travelled to Paris to see The Marriage of Figaro by Beaumarchais, Holcroft had requested a copy of the script but was refused. So, over ten nights in September 1784, he and a friend attended the performance and recorded the entire script. In December that same year, with no respect for creative copyright, Holcroft took to the stage at Covent Garden in the role of Figaro for its first performance in Britain.

A decade later in 1792, Holcroft produced his best-known play The Road to Ruin. Let us leave Holcroft to bask in his glory for a little while, and I will return to his life after 1792 in due course.

#23

In print at last after 150 years: 'The Life of William Nicholson, by his Son'

February 24th, 2018share this

I was extremely fortunate in having been signed by one of the leading independent publishers - Peter Owen Publishing. This was the first publisher that Iapproached (so very fortunate indeed) and is surely testament to the importance of Mr Nicholson, rather than my own humble credentials.

As the main biography is taking much longer than anticipated (see below), we decided to publish The Life of William Nicholson by his Son as a prelude - exactly 150 years after it was written in 1868. This rare manuscript has been held by the Bodleian Library since 1978.

In addition to the edited text of The Life of William Nicholson by his Son, the book also includes:

- a timeline of Nicholson's life, work and inventions;

- details of Nicholson's published works;

- Nicholson's patents and inventions;

- Nicholson's list of members of the coffee house philosophical society of the 1780s (not as complete as in Discussing Chemistry and Steam by Levere and Turner …, but indicative of Nicholson's associates at the time); and

- committee Members of the Society for Naval Architecture of 1791.

Design agency Exesios have done a super job of the cover, and there is a special treat on the inside with:

- a map of all Nicholson's known homes on (Drew's map of 1785); and

- the drawings from the 1790 cylindrical printing patent.

I'm delighted that Professor Frank James of UCL and the Royal Institution has written an afterword which focuses on Nicholson's scientific contributions. Considering his literary associates, Professor James also suggests why Nicholson was never made a member of the Royal Society, despite his many achievements.

The modern biography of William Nicholson (1753-1815)

With 110,000 words under my belt, I was beginning to think that the end was in sight on the modern biography - until I met up with Hugh Torrens, Emeritus Professor of History of Science and Technology at University of Keele, to chat about some of the civil engineering issues.

Our first meeting resulted in a very exciting list of 29 items of further research which will keep me busy researching and writing for several months.

Meanwhile, you can keep up to date with news and developments here on the blog.

#22

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

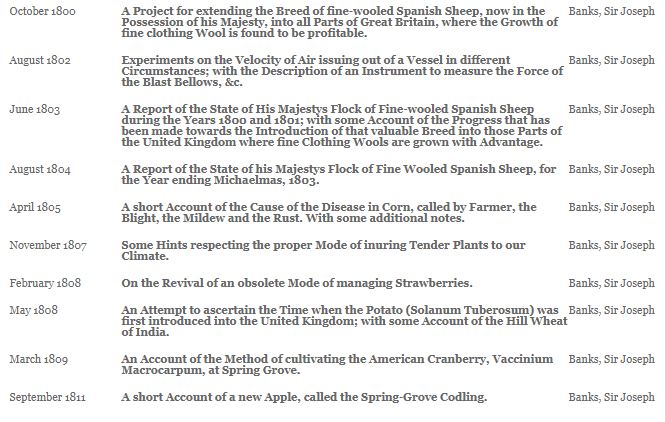

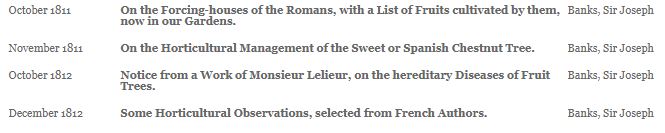

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

Invention #1 - Nicholson’s Hydrometer

January 15th, 2018share this

A hydrometer is a device for measuring a density (weight per unit volume) or specific gravity (weight per unit volume compared with water). It was also called an aerometer, a gravimeter or a densimeter.

On 1 June 1784, Nicholson wrote to his good friend Mr. J. H. Magellan with: ‘A description of a new instrument for measuring the specific gravities of bodies’.

According to Museo Galileo, hydrometers date back to Archimedes and the Alexandrian teacher Hypatia, but the second half of the nineteenth century saw the design of several types which were well-used in industry of which “the better-known models include those developed by Antoine Baumé (1728-1804) and William Nicholson (1753-1815)”.

Nicholson’s paper, which does not seem to be accompanied by a drawing, was published the following year in the Memoirs of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (London: Warrington, 1785) 370–380, and can be accessed via Google Books

In the first edition of Nicholson’s A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, Nicholson wrote an article about the hydrometers invented by Baumé – one for spirits and one for salts - which had never been used in this country, but never mentioned his own earlier invention.

In June 1797, Nicholson published a translation of a paper that had been read in France at the National Institute by Citizen Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveau (1737-1816), and then published in the Annales de Chimie. Nicholson points out that ‘this translation is nearly verbal’ as he finds himself writing about his own invention.

Comparing Nicholson’s hydrometer with that designed by Fahrenheit which he described as ‘not fit for the hand of the philosopher’, Guyton de Morveau says:

“The form which Nicholson gave some years ago to the hydrometer of Fahrenheit, rendered it proper to measure the density of solids. At present it is very much used. It gives, with considerable accuracy, the ratio of specific gravity to the fifth decimal,water being taken as unity. … It does not appear that any better instrument need be wished for in this respect.”

Of all of Nicholson’s inventions, this one still bears his name and is called Nicholson’s hydrometer today. Examples can be found in several museums, and it is possible to purchase a modern version for use in school experiments for just a few dollars.

The Oxford Museum of the History of Science kindly showed me their Nicholson’s hydrometer from 1790.

Others can be found at:

HarvardUniversity Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

St.Mary's College in Notre Dame, Indiana

The VirtualMuseum of the History of Mineralogy (Private collection)

Sadly, I couldn’t find a video online with a demonstration of Nicholson's hydrometer being used. If anyone knows of one, or feels the urge to produce one, I would love to share it on this website.

#20

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order