UCL PhD students from Ucell recreate Nicholson & Carlisle’s splitting of water with battery at Bloomsbury Festival (Video)

December 20th, 2020share this

When I was asked to participate in the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival, with the Friends of St George’s Gardens, I was delighted to have an opportunity to spread the word about William Nicholson (1753-1815) and his interesting life.

I was especially happy when the FoSGG team proposed hiring an actor to play Mr Nicholson, and had great fun writing the script … up to the point when Nicholson’s interests turned to science.

It was easy to paint a vivid picture of life at sea with the East India Company, the theatrical shenanigans with Thomas Holcroft and the revolutionary and political events of that period.

But communicating about Nicholson’s experiments and the achievement of splitting water (with his colleague Anthony Carlisle) was a different matter.

I’ll confess to being a late-bloomer when it comes to any interest in science. My younger self would be astonished to learn that one day I might be interested about the history of science – nevermind reading and writing about it. I’m certainly not equipped to talk or even demonstrate it.

But just around the corner from St George’s Gardens is University College London, which was also involved with the Bloomsbury Festival, and which happens to have an electrochemistry outreach group. Several PhD students were keen to spread the word about the future of clean energy and the potential for hydrogen fuel cells – a technology which can trace its history in a direct line to Nicholson & Carlisle’s experiment in May 1800 in the house in Soho Square. (See this guest blog from Alice Llewellyn- How the discovery of electrolysis has changed the future’s energy landscape).

The UCL team comprised Alice Llewellyn, Harry Michael, Keenan Smith and Zahra Rana as presenters, and Katrina Mazloomian as videographer. They brought the science to life in a wonderfully engaging way.

This extract from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ is now on the Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account and shows Mr Nicholson (played by Julian Date) talking to the PhD students as they:

- recreate Nicholson & Carlisle’s splitting of water with battery;

- describe how the discovery of electrolysis is useful today;

- explain the connection with global warming and clean energy; and

- describe the hydrogen fuel cell.

This is followed by a Q&A session recorded from the online event. With questions including:

- How does the oxygen and hydrogen know to come out of separate tubes?

- Has the problem of holding and gradually releasing the hydrogen been solved?

- Fuel cells are nice, but you need electricity to generate the hydrogen. Will the UK have enough capacity to generate enough electricity from non-fossil fuels?

Thankfully our team of experts from UCL answered these questions most interestingly, and in plain English as you can see on the second of two videos from the Bloomsbury Festival.

Click here to watch:

In Conversation #2: Ucell recreate Nicholson (1753-1815) splitting water by electrolysis, May 1800

#37

Eighteenth Century Mr Nicholson launches his YouTube Channel

December 15th, 2020share this

When William Nicholson launched his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts in 1979, part of his motivation was to speed up the transfer of scientific knowledge.

If he lived today, he would surely have embraced social media for that purpose - never lowering himself to insults or trolling!

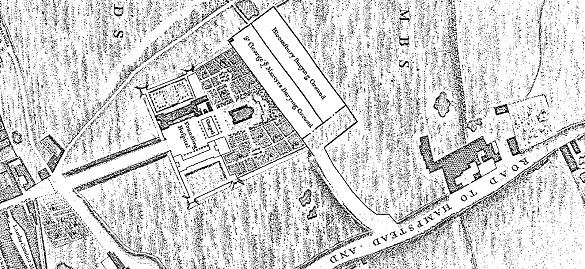

Now he has added a Nicholson’s Journal YouTube account to his media channels, and we are able to share excerpts from ‘In Conversation with Mr Nicholson’ a performance for the Bloomsbury Festival 2020 which took place in the open air of St George’s Gardens, London where Nicholson is buried.

Directed and introduced by Ian Brown, episode one is the historical part where his biographer Sue Durrell interviews Nicholson who has returned from his grave in the gardens to talk about his life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nicholson is brought to life most ably by actor Julian Date, who reminisces about his life at the crossroads of Georgian arts, literature, science, and commerce, and discusses the importance of his discovery in splitting water using Volta’s battery, alongside his friend Dr. Carlisle.

The short three excerpts in this video cover:

• Working for Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam and at the General Chamber of Manufacturers

• Nicholson’s motivation for launching his Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts; and

• Remembering Humphry Davy and the Royal Institution and recalling the experiment with Anthony Carlisle where they split water into hydrogen and oxygen in May 1800.

This is the first of two videos from this event. Part two shows demonstrations of the experiment and discusses its implications in the quest for clean energy.

Julian Date is represented by Hilary Gagan Associates.

#36

Mary Wollstonecraft, PPH and eighteenth century maternal care

November 26th, 2020share this

With all the fuss about the Mary Wollstonecraft statue, it reminded me that one of the topics which was on my mind was the state of maternity care at the end of the eighteenth century. William and Catherine Nicholson seemed to do pretty well with at least 10 kids making it to adulthood. (One infant death is recorded, one of the twelve children still remains a mystery).

Caitlin Moran’s response on Twitter to the statue in Newington Green was ‘If you want to make a naked statue that represents "every woman", in tribute to Wollstonecraft, make it e.g. a naked statue of Wollstonecraft dying, at 38, in childbirth, as so many women did back then - ending her revolutionary work. THAT would make me think, and cry.’{10 November 2020}

So, I turned to Lisetta Lovett, a retired consultant psychiatrist and medical historian, and asked whether this standard of maternal care was normal for the time? Or was Mary Wollstonecraft just particularly unlucky in her medical advisers?

The information which I had compiled on the birth of Mary’s baby with William Godwin was that:

Mary went into labour on Wednesday 30 August, choosing to hire a midwife but no nurse. Godwin described the role of the midwife ‘in the instance of a natural labour, to sit by and wait for the operations of nature, which seldom in these affairs demand the operation of art.’

Little Mary was born at 11.20pm and, sometime after 2.00am, Godwin who was keeping out of the way in the parlour, was informed that the placenta had not been removed. A physician was called for and he removed the placenta ‘in pieces’. The loss of blood was ‘considerable’ and Mary’s health did not improve over the next few days, despite a second doctor visiting and pronouncing that Mary was ‘doing extremely well’.

Godwin wrote that ‘On Monday, Dr Fordyce forbad the child having the breast, and we therefore procured puppies to draw off the milk.’

Then on Wednesday, following a recommendation by family friend Dr Carlisle, ‘it was now decided that the only chance of supporting her through what she had to suffer, was by supplying her rather freely with wine … I neither knew what was too much, nor what was too little. Having begun, I felt compelled under every disadvantage to go on. This lasted for three hours.’

Dr Fordyce was no beginner - see wikipedia - although we do not know if he was the attending doctor on the first two occasions. Dr Carlisle was a close family friend who went on to become the Surgeon Extraordinary to King George IV in 1820.

Lisetta, whose book Casanova's Guide to Medicine: 18th century Medical Practice is due to be published by Pen and Sword Ltd in April 2021, kindly provided the following insights into the medical profession and the little that we know about Mary Wollstonecraft’s death:

The information given here, taken from William Godwin’s diary as well as other sources, raises more questions than it answers. However, it looks like Mary suffered from a post-partum haemorrhage, the cause of which seems to have been a retained placenta.

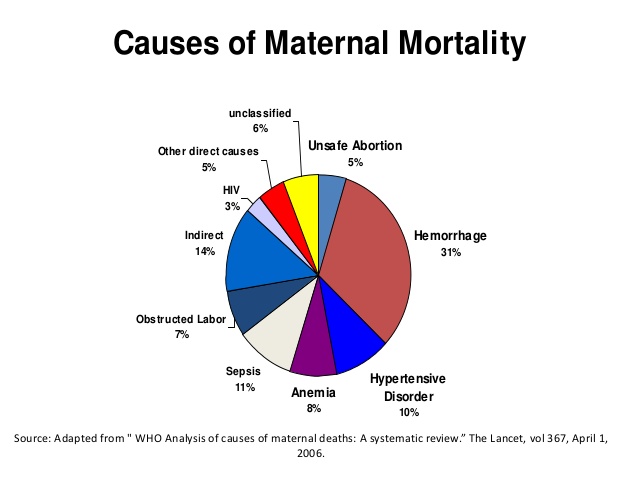

The medical definition of a retained placenta is one that has not been expelled within 30 minutes of delivery. This is still a leading cause of maternal death worldwide, and treatment today is intervention with oxytocin either in the third stage of labour or after delivery and, if this fails, then manual removal under anaesthesia.

By the 19th century, obstetrics had become a medical specialty in its own right, much to the irritation of the midwives. Following the advent of man-midwives, medical doctors moved into the specialty. Neither Dr Fordyce or Dr Carlisle are recorded as having such expertise, but maybe this is not so surprising given that obstetrics as a medical specialty developed a little after their time.

There is a telling quote from a Dr Edgell in On Obstetric Practice, in 1816: "I believe it was an aphorism of the late Dr Clarke, that no woman should die of haemorrhage if an accoucheur is called early...".

Post-partum haemorrhage was a well recognised and potentially lethal complication of child-birth. Accoucheurs applied a variety of treatments to manage it and knew that a quick response could be life-saving. These treatments ranged from a hand in the uterus to stimulate contraction of the uterus and therefore expel the retained placenta (see Davis David in Principles and Practice of Obstetrics 1832-65) to the use of cold water on the stomach, or even injected in the rectum.

The obstetric literature of the early 19th century reveals that there was a lot of medical debate about what measures were most effective, including whether stimulants like brandy or wine should be administered. As the Covid pandemic illustrates, doctors are often in disagreement and so we should not be surprised.

Clearly, Mary would have been better off with an experienced accoucheur, medically trained or not, present throughout the birth ready to respond to any complications. The midwife at least knew that a retained placenta was bad news and informed Godwin who called for a physician. He tried to remove the placenta but probably did not do so completely; a difficult task without the benefit of an anaesthetic and a dreadful ordeal for Mary. For whatever reason, he did not continue to attend her which was a pity.

It is not clear if Mary continued to bleed or not but, given the second doctor's optimism, it sounds as if the bleeding appeared to have stopped.By the time Dr Fordyce is called, it is four days post-partum! He may have suggested the puppies in order to stimulate the uterus to contract and thereby encourage the expulsion of any remaining placenta as suckling induces the body to produce oxytocin. But why not allow the baby to suckle Mary?

Perhaps, she already had a wet nurse, and the doctor wanted to avoid disruption to the baby's feeding. That being said, the cult of breast-feeding your own baby had become popular in the 18th century especially in France where Rousseau’s re-evaluation of maternity was influential. Mary had spent several turbulent years living in France and was no doubt aware of this.

Mary obviously was deteriorating, in part because she continued to lose blood (perhaps internally so it was not obvious) leading to severe anaemia. She may have also developed septicaemia although there is no mention of her having a fever. Ironically, one cause of this could have been manual placental removal. At this time there was little, if no notion, of the importance of keeping one’s hands clean to prevent dissemination of germs.

When Carlisle finally sees her, I think he knows she is going to die and this is why he suggests wine as a 'tonic', not as a treatment but rather as an anaesthetic to make her last hours a little more bearable.

Godwin must have bitterly regretted his early laissez faire comment about childbirth. It is a great pity that he had not employed from the outset an experienced accoucheur, although even so Mary might have died. At this time, childbirth was one of the most dangerous challenges a woman might be obliged to address.

You can follow Lisetta Lovett on her blog Casanova's Medicine.

Today, according to the WHO, about 14 million women around the world suffer from postpartum haemorrhage every year. This severe bleeding after birth is the largest direct cause of maternal deaths. And of course, in addition to the suffering and loss of women’s lives, when women die inchildbirth, their babies also face a much greater risk of dying early. Shockingly, 99% of the deaths from PPH occur in low- and middle-income countries, compared with only 1% in high-income countries.

#35

Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture and the feminists’ new clothes

November 15th, 2020share this

I guess I feel that I have a very small right to claim a connection to Mary Wollstonecraft, as my 5 x great grandmother Catherine Nicholson was one of the two close friends (along with Eliza Fenwick) who stayed with and comforted Mary Wollstonecraft in her dying days.

Catherine wrote to William Godwin after his wife’s death to say:

Myself and Mrs Fenwick were the only two female friends that were with Mrs Godwin during her last illness. Mrs Fenwick attended her from the beginning of her confinement with scarcely any interruption. I was with her for the four last days of her life …

She was all kindness and attention & cheerfully complied with everything that was recommended to her by her friends. In many instances she employed her mind with more sagacity upon the subject of her illness than any of the persons about her …

I noticed the fundraising appeal for the statue in 2019 – but it was not clear how much they were trying to raise; how much was still needed; and how it would be spent. There was no information about the finances on the website, only the vague statement “A capital sum for the memorial and a revenue source for the Society will ensure that Wollstonecraft’s legacy and learning will continue.” I was simply seeking to clarify the financial position, but my polite enquiry elicited a rather frosty response, suggesting that I should find another memorial to support.

I’m a fan of figurative sculptures and am lucky enough to live near to the National Memorial Arboretum. As you walk round, you cannot fail to be moved by the way that the sculptures make a historic figure lifeisize (or larger) making more real the boy who represents all those shot at dawn, thechild evacuees, or the ladies Women’s Land Army and Timber Corps. I’d never heard of lumber jills before, but seeing the memorial prompted me to find out more.

So, OK I’ll admit that I’m not very radical in my taste for sculptures, And Mary Wollstonecraft was a radical, so she needs a radical sculpture – right?

Mary Wollstonecraft was strong and adventurous, working as a journalist she headed off to Paris to cover the revolutionary troubles for the publisher Joseph Johnson. But, I’m afraid I cannot see strength and courage in this sculpture.

She was a thinker, an author, and an educator. How is this portrayed in the sculpture? And how is it meant to inspire young women toexpand their minds?

The Mary on the Green website states that “Her presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people in Islington, Haringey and Hackney” … and The Wollstonecraft Society’s objectives are “to promote the recognition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s contribution to equality, diversity and human rights.”

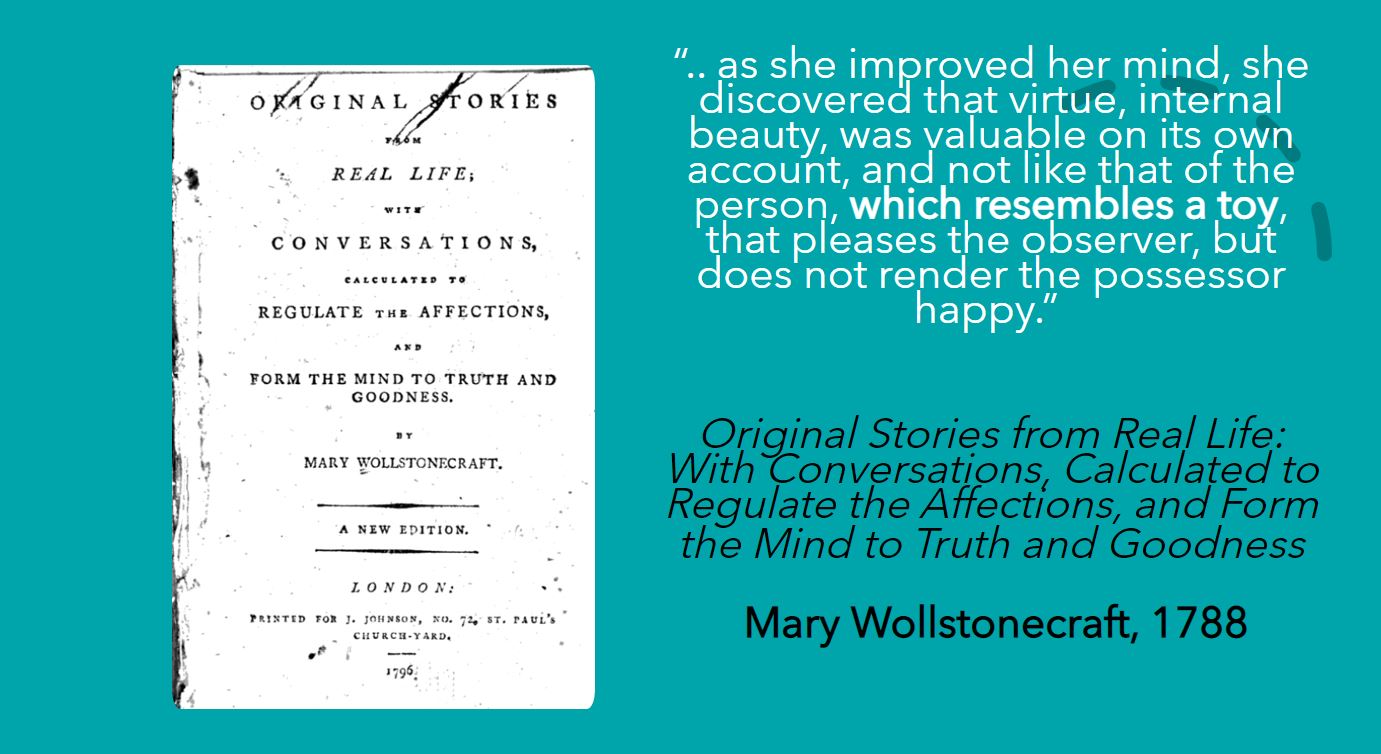

In Original Stories from Real Life: With Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (1788), Wollstonecarft wrote of a woman who lost her good looks to the small pox and “.. as she improved her mind, she discovered that virtue, internal beauty,was valuable on its own account, and not like that of the person, which resembles a toy, that pleases the observer, but does not render the possessor happy.”

I’m struggling to see how any child who sees this toy-like sculpture will come away with the message that cultivating the mind is more valuable than looks.

On the other hand, (having once accompanied a group of 11-year olds on a school trip to Paris) it is not hard to imagine the giggling and sexist comments that might emerge among some and the embarrassment that might be felt by others.

I don’t envy the teacher who has to create a lesson plan around this educational trip!

#34

Lady Luck is smiling on us ... Outdoor walks and talks proceed under Tier 2 London Lockdown

October 15th, 2020share this

London is now in Tier 2 lockdown, which means that households in areas under high alert (Tier 2) can only mix with others outdoors, in groups of six or fewer.

It seems that Lady Luck has smiled on St George's Garden's once again, and as our event is an 'outdoor talk' with plenty of space for social distancing, then it still has the green light to proceed.

Ticketholders must wear a mask, stay in their bubble, avoid mingling and keep their distance from the performers.

Click here for the latest update from the Bloomsbury Festival Director.

A long shot … will our Bloomsbury Festival live event survive the 'Covid-19 circuit-break'?

October 12th, 2020share this

A short history of the ups and downs of organising a live event for the Bloomsbury Festival during the coronavirus

On 17 March 2020, just a few days before our world turned upside down due to the coronavirus, I received an email from Diana at the Friends of St George’s Gardens (where Nicholson is buried):

“This is just a long shot. But how would you like to do a walk round St George’s Gardens and talk about William Nicholson in late October, as part of the Bloomsbury Festival? We did this in 2018 for Zachary Macaulay with two actors in costume – Zachary and his wife. … “

A few days later on 23 March, the nationwide lockdown was announced by the government. The prospect of 12 weeks at home provided the perfect opportunity to write up a script, and with everything looking so bleak, this was something exciting to look forward to.

At that time, although all summer events were being cancelled, we all thought that life would be back to normal after a few months and October was far enough ahead to be safe. How incredibly naïve!

By the end of April, we’d all embraced the powers of Zoom and a meeting with the Bloomsbury Festival team, led by Rosemary Richards, explained that they were going ahead with various contingency plans, and we should plan an online version as a backup.

I was also interested to see that UCL were participating in the festival – for I knew they had a history of science faculty. As I had started writing the script and reached the scientific bits, I was wondering how we could get the discovery of electrolysis across in an interesting and engaging way – as this was distinctlynot my area of expertise.

Having seen that the festival team had been involved with the science festival GravityFest, I asked if they might have any useful contacts at UCL. Fortunately on they wrote to say “UCell are happy to help/collaborate with you in giving a talk at the Bloomsbury festival” and Alice, Harry and Keenan agreed to comealong and recreate the water-splitting experiment from May 1800 and then demonstrate how electrolysis plays a role in clean energy production with their hydrogen fuel cell.

In May Diana emailed to mention “another committee member, Ian Brown, who is a theatre director and will have good ideas about how to make the most of a story.” Looking him up online to find he had run the highly regarded West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds for a decade, I didn’t know whetherto be delighted or petrified. The sum total of my dramatic experiences to date comprised playing Mary in a nativity play at infant school and a mime on a student trip to Santander a few decades ago – neither role having had any script – what had I let myself in for?

Thankfully, Ian turned out to be delightful and thoroughly put me at ease. He suggested the performance should take the form of an interview with Nicholson’s ghost (great idea!) and was also very pragmatic about the format of the online version when my multi-media ambitions ran away with themselves. Ian also took on the role of finding an actor, when it turned out that my friend was in a high-risk group and was shielding could be confined indefinitely (as it seemed at the time).

Details of the event had to be finalised for the programme by the end of May, and so it was agreed to perform live on the first Saturday 17th and the online event was scheduled for Tuesday 20th October. The title of the talk was agreed as “In conversation with Mr Nicholson” referring to the conversazione evenings which were hosted by Georgians.

The running order started with me interviewing the ghost of Nicholson about his life up to the point of the experiment in 1800 – then we would introduce the UCell team and Nicholson would take up the baton and ask them about their experiments and the future usefulness of his work. I was thrilled that we would be able to show how relevant his work had been to the future of clean energy, and in a way that would be much more visually interesting for an audience.

However, this was not without a few challenges of its own, as the UCell team had to get approval from the university for their participation and use of the fuel cell stack (a very valuable piece of kit, the size of a large supermarket trolley). And while we could record the interview on zoom at any time for use in the online version, the only chance to video the experiments would be on the 17th October (Covid-19 permitting).

We all pressed on in good faith, and I booked the last week of May off work to get the script finalised and over to Ian.

On 18 June, the festival team emailed to say “As you know, we are working with the current, and ever-changing, government advice regarding Covid-19 and social distancing, and of course the safety of our performers and festival goers is our absolute priority. With this in mind, we have come to the decision to cap the number of participants for your talk to 20 participants for the time being. As you can imagine, this is to protect the safety of the people attending, and yourself. If nearer the time restrictions are relaxed, we will release more tickets.” Having scoped out the layout in the gardens the FoSGG team were later able to increase this to a maximum of 30.

At the beginning of July, Ian helped me to shape the script – adding more depth to the character of Nicholson and his family, explaining all the other characters, adding some gossip and eliminating non-sequiturs!

We still didn’t have an actor for Mr Nicholson. Hugh Jackman was of course isolating in Australia, so I spent an evening looking through actor directory websites – mercilessly judging men solely on their appearances.

Meanwhile, lockdown had not ended, and we were all still working at home. It was necessary to decide on whether to charge participants an entry fee, and in the end it was decided that it was “a bit more than a talk, with a scientific demo and a speaker in costume” so fees were set at £8 for the live event and £5 for the online event. The Bloomsbury Festival typically do a 50/50 split with paid ticketed events, and they have a “box office intern” and volunteer present to deal with last minute onsite tickets and to take payments. Soon, the contract was signed and Diana was looking into whether we should or could use microphones.

On 21 July, Ian emailed to say he had found a potential Mr Nicholson “I got an email from a local actor this morning - he’s a barrister as well as an actor. Going to meet him.” A week later Julian Date had joined the team – a family barrister by day, I was amazed that he would have the head space to learn so many lines as well as running court cases up to the performance, but apparently these use different parts of the brain.

August and September saw us all rehearsing on Zoom and fine tuning the script. It was quite enchanting to see Jules bringing Mr Nicholson to life after the character had been rattling around in my brain for so long.

The UCell team could show us some of their science online – with a mini hydrogen-powered car – but we will not get the full picture until the big day. They normally participate in many live events, (and should have been in Florida for one of our rehearsals), but we were the only live event that was still on their calendar for this year.

Finding a costume for Julian turned out to be another challenge as all the theatres were closed, and consequently so were all the costumiers. Eventually a service in Bristol was identified which provides costumes to the BBC and could send it by post, so Julian had to provide his vital statistics.

September ended, and despite a variety of lockdown measures and a recent new restriction of group sizes to a maximum of six people, the event was still not cancelled. It was outdoors and thanks to Sue Heiser of FoSGG and her work on the risk assessment, it will be possible to keep everyone at an appropriate distance.

Tickets were selling and by October the live event quickly sold out its 30 tickets. But we still hadn’t nailed down the details of the online event, and while we thought we would be able to record all the interview on Zoom and the experiments on video, we were not sure how this would all come together and then be broadcast. Fortunately, Rosemary Richards called in Hannah a digital producer and Mirabel who is also at UCL and doing science outreach. There was a debate about the comparative merits of YouTube and Zoom, but the latter has the added advantage of participation and so we can have a Q&A at the end.

This put us on track and reassured us that someone who knew what they were doing would be pressing all the Zoom buttons on the day. I’ll be providing a live introduction before the interview and linking to the video, then managing the Q&A with someone from the UCL team who will handle the scientific questions.

On 7th October, we were still waiting to hear from UCell team whether they had approval from UCL to participate, and thankfully this came through and they can bring the hydrogen fuel cell stack. The costume has arrived in London, and everything is planned for next Saturday, the 17th October.

With coronavirus cases rising by the day again, and with les than a week to go, we are waiting with bated breath to hear whether there will be a “circuit-breaker” lockdown over half term or a local lockdown affecting London, and whether the live event will still go ahead.

It’s a long shot, but we re keeping our fingers crossed that the show will go on

#32,

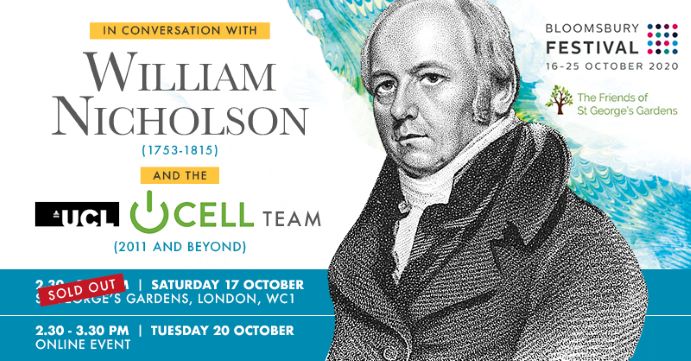

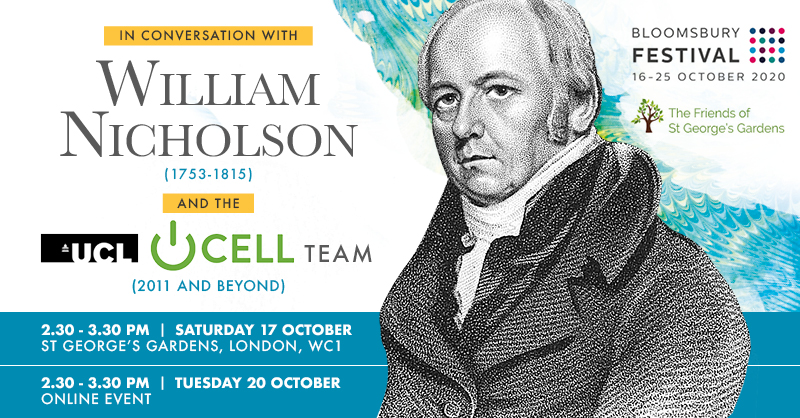

17 and 20 October - In Conversation with William Nicholson and the UCL Ucell clean energy team at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival

August 28th, 2020share this

It is very exciting to announce that William Nicholson (1753-1815) will be making an appearance at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival alongside the UCL hydrogen fuel cell demonstrator!

Saturday 17 October 2020,

2.30 – 3.30 pm – Live event in St George’s Gardens, London, WC1N 6BN at thewest end.

Tickets £8 (£6 concs) – Clickhere for details.

Tuesday 20 October 2020

2.30 – 3.30pm – Online event, via the Bloomsbury Festival at Home

Tickets £5 – Clickhere for details.

How the discovery of electrolysis has changed the future’s energy landscape

August 25th, 2020share this

A guest blog by Alice Llewellyn from UCell, the electrochemical outreach group at UCL

Shortly after the invention of the battery in the form of a voltaic pile by Alessandro Volta in 1800, William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840) discovered that water can be split into its constituent elements (hydrogen and oxygen) by using electrical energy.This phenomena is termed electrolysis and is the process of using electricity to produce a chemical change. Electrolysis was a critical discovery, which shook the scientific community at the time. It directly demonstrated a relationship between electricity and chemical elements. This fact helped scientific legends – Faraday, Arrhenius, Otswald and van’t Hoff develop the basics of physical chemistry as we know them.

Fast forward to today, and we are faced with one of the greatest challenges – climate change. This effect has accelerated the search for alternative fuels and energy storage devices fin order to decarbonise the energy sector. Burning fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) for energy is the main cause of climate change as it produces carbon dioxide gas which leads to a greenhouse effect and the warming of our atmosphere.

A huge contender for alternative fuels is hydrogen. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe. However, it does not typically exist as itself in nature and is most commonly bonded to other molecules, such as oxygen in water (H2O). This is where electrolysis plays a key role. Electrolysis can be used to extract hydrogen from the compound which can then go on to be used as a fuel. Moreover, if a renewable source of energy is used (for example wind or solar) to provide the electricity required to split the water, then there is no carbon footprint associated with this hydrogen production.

Hydrogen can then be used in fuel cells to produce electricity. Fuel cells are electrochemical energy devices, they convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy without any combustion. The way in which a fuel cell works is in fact the reverse process of electrolysis. In a fuel cell, hydrogen is split into its protons and electrons which then react with oxygen to produce water, electricity and a little bit of heat. As the only side product of this reaction is water, fuel cells are a very clean way to produce electricity.

Energy from renewable sources (wind, solar…) is intrinsically intermittent. Depending on the season or time of the day more or less energy is produced. To make sure the supply of energy is secure and stable, energy needs to be stored when an excess is produced and later fed back into the grid when needed. Water electrolysis offers grid stabilization. When a surplus of energy is available, e.g. during the day when the sun is shining, some of this energy is used to produce hydrogen. This hydrogen can then easily be stored in tanks. Whenever more energy is needed, e.g. when it is dark, hydrogen is taken from tanks and fuelcells are used to release the energy stored in the hydrogen.

Not only can hydrogen be used for grid stabilisation, but this can also be used to transform the transport sector, which contributes to around a quarter of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions. Fuel cell vehicles are one of the solutions that have been adopted to tackle this problem and are classed as zero-emission vehicles (only water comes out of the exhaust).

In 2019, London adopted a fleet of hydrogen-powered double decker buses – a world first! As more people start to learn about this technology, more fuel cell vehicles can be spotted on our roads.

Without the discovery of electrolysis by Nicholson and Carlisle in 1800, it might not be possible to produce pure hydrogen for these applications in such an environmentally-friendly way, making the fight against climate change a more difficult task.

*

About our guest author Alice Llewellyn

Following a masters project synthesizing and testing novel battery negative electrodes, Alice Llewellyn, started her PhD project in the electrochemical innovation lab at UCL, primarily using X-ray diffraction to study atomic lattice changes in transition metal oxide cathodes during battery degradation. Alice co-runs the electrochemical outreach group UCell.

UCell is a group of PhD and masters students based at University College London, who are passionate about hydrogen, clean technologies and electricity storage and love sharing their knowledge and experience to the general public through outreach, taking their 3 kW fuel cell stack to power stages, thermal cameras and, well, anything that needs powering! In a time of a changing energy landscape, they aim to show how these technologies are starting to become a regular feature in our everyday lives.

#30

Termites tuck into Nicholson’s Journals in Bombay in 1859

August 9th, 2020share this

Here is an extract from the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, from Monday 28th November 1859 telling of a sad fate for Nicholson’s Journal.

“It is with much regret that the Committee have to inform the Society that the White Ants, which infect the Town Hall throughout, have found their way into the Library, and destroyed many of the books.

This was first discovered in September 1858, and since that there have been several incursions … during which 12 works or 33 volumes have been destroyed, and 12 works or 38 volumes slightly injured; fortunately those which have been destroyed have chiefly consisted of Novels, the others have been works in the classes of Classics and Chemistry; - “Nicholson’s Journal” however, has severely suffered.”

#30

Solving the C18th puzzle of scientific publishing

July 13th, 2020share this

A guest blog, by Anna Gielas, PhD

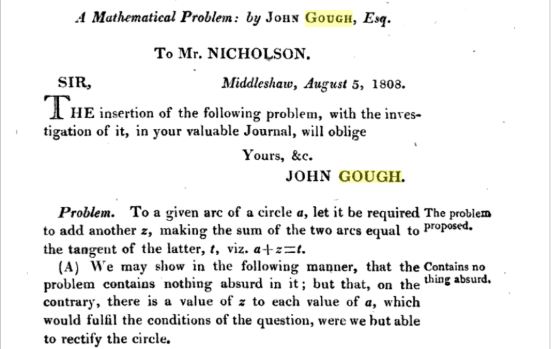

William Nicholson made Europe puzzle. Continental men of science translated and reprinted articles from his Journal on Natural Philosophy,Chemistry and the Arts on a regular basis—including the mathematical puzzles that Nicholson published in his column ‘Mathematical Correspondence’.

When Nicholson commenced his editorship in 1797, his periodical was one of numerous European journals dedicated to natural philosophy. Nicholson was continuing a trend that had existed on the continent for over a quarter of century. But at the same time, Nicholson was committing to a novel form of philosophical communication in Britain. The British periodicals dealing with philosophy and natural history were linked with learned societies. Besides the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, numerous philosophical societies in other British towns, including Manchester, Bath and Edinburgh, published their own periodicals. The London-based Linnaean Society, which had close ties to the Royal Society, also printed its transactions.

Nicholson’s editorship did not have any societal backing. He did not conduct his periodical in a group, but by himself. These circumstances made his Journal something different and novel—maybe even revolutionary. In the Preface to his first issue, Nicholson confronted the very limited circulation of society and academy-based transactions and their availability to the ‘extreme few who are so fortunate’. He made it his editorial priority to reprint philosophical observations from transactions and memoirs—to make them accessible to a wider audience.

Considering his friendship with the radical dramatist Thomas Holcroft and his collaboration with the political author William Godwin, we can think of Nicholson’s editorial priority in political terms: he wished to democratize philosophical communication. Personal experiences could have played a role here, too. Nicholson appears to have initially harbored some admiration for the Royal Society and its gentlemanly members. But he did not become a Fellow due to his social background. Whether he considered his inability to be part of the Society a social injustice is not clear. But this experience likely played a role in his decision to edit and reprint from society transactions.

There seems to be a political dimension to Nicholson’s editorship—yet the sources available today do not allow any straight-forward reading of the motives for his editorship. He did not present his editorship as a political move. Instead, he used the rhetoric of his contemporaries—the rhetoric of utility: ‘The leading character on which the selections of objects will be grounded is utility’, he wrote in his Preface. The Journal was supposed to be useful to ‘Philosophers and the Public’.

Nicholson had acquired the skills necessary for editing a periodical over many years. It seems that his organizing role in a number of societies and associations was particularly helpful to hone such abilities—for example, his membership at the Chapter Coffee House philosophical society. In mid-November 1784, Nicholson and the mineralogist William Babington were elected ‘first’ and ‘second’ secretaries of the society. During the gathering following his election, Nicholson appears to have raised 13 procedural matters for discussion and action. According to Trevor Levere and Gerard Turner, Nicholson ultimately ‘made the meetings much more effective and disciplined’.

His organizing role brought and kept him in touch with most of the Chapter Coffee House society members which enabled him to expand and affirm his own social circle among philosophers. So much so, that some of the society members would go on to contribute repeatedly to Nicholson’s Journal. As the ‘first’ secretary, Nicholson gained experience in steering a group of philosophers and experimenters towards a productive and lasting exchange—a task similar to editorship.

Nicholson was skilled in fostering and maintaining the infrastructure of philosophical exchange. His contemporaries were well aware of it and sought his support on a number of occasions. Among them was the publisher John Sewell who invited Nicholson to become a member of his Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Here, Nicholson and Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and Vice-President of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, had one of two conflicts.

Philosophical societies in late eighteenth-century London tended to have presidents and vice-presidents, committees and hierarchies. More often than not, these hierarchies mirrored the members' actual social ranks. As an editor, outside of a society, Nicholson was free from hierarchies. He could initiate and organize philosophical exchange as he saw fit—which likely made editorship attractive to him.

For Nicholson who was almost constantly in financial difficulties, editing was also a potential source of additional income. After all, the same month the first issue of his Journal came out, Nicholson's tenth child, Charlotte, was born. But the Journal did not become a commercial success. Yet, he continued it over years, until his health deteriorated. Non-material motives seem to have outweighed his monetary needs.

His journal was an integral part of Nicholson’s later life—particularly when he no longer merely reprinted pieces from exclusive transactions. After roughly three years since the first issue appeared, his Journal began to turn into a forum of lively philosophical discourse. In the issue from August 1806, for example, he informed his contributors and readers of the ‘great accession of Original Correspondence’, which he—whether for the reason of ‘utility’ or democratizing philosophy—published in later issues rather than foregoing publication of any of them.

Outside of Britain, the Journal was read in the German-speaking lands, Russia, Netherlands, Scandinavia, France and others. Nicholson made Europe puzzle indeed. He united geographically as well as culturally and socially distant individuals, bringing European men-of-science closer together.

Further reading:

Anna Gielas: Turning tradition into an instrument of research: The editorship of William Nicholson (1753–1815),

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1600-0498.12283

#29

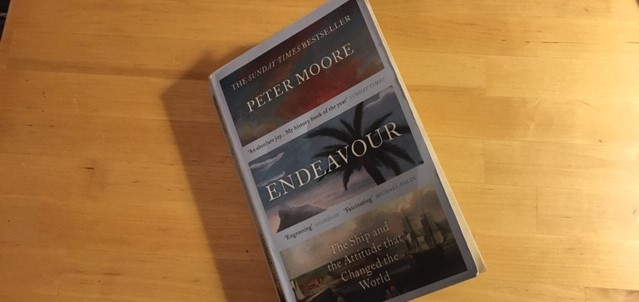

Book Review: Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World

February 9th, 2020share this

At the age of 15, my sons were fairly obsessed with sportand under pressure to work towards impending exams. It is hard to imagine sending them to theother side of the world by sea with the East India Company at that age, as wasthe case with young William Nicholson. It is hard to imagine, the seafaring bustle of the Thames when shipswere built of wood, sails were sewn by hand and sailors could be seen hangingfrom the rigging as he boarded his first Indiaman in 1768.

Nowadays there are daily flights from London to Guangzhou (Cantonto Nicholson) with a journey time of less than ten hours. In 1768, the journeywould take several months and (not being any sort of sailor) it is hard toimagine the life on board – the routines, the food, the highs and lows – that wouldhave been Nicholson’s life.

Fortunately, under my Christmas tree this year was a copy ofPeter Moore’s Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World, abook tracing the history of this bark’s life from before it was launched in1764 through its early life in the coal trade between London and the NorthEast, along its famous journey to the South Seas to observe the Transit ofVenus with Captain Cook and Joseph Banks, and finally her role in one of thegreatest invasion fleets in British History.

Moore paints such a vivid picture of the bark and the charactersaboard, the environment in port or at sea, and the political and economicsetting – that it was a very enjoyable read and easy to imagine Nicholsonpassing the Endeavour in the Thames or the Channel as they set sail in the sameyear.

It was charming to meet the young Sir Joseph Banks when hewas full of fun and enthusiasm, eagerly collecting thousands of botanical specimens- for Nicholson’s encounters with Banks two decades later had left me with theimpression of a grand but arrogant and entitled character.

As a young man crossing the equator for the first time, andwithout the means to pay a fine to avoid the experience, Nicholson will havehad to partake in the traditional dunking ceremony which was described in greatdetail when Endeavour crossed in October.

While Cook’s South Sea discoveries have been told manytimes, Moore then traces the history of this vessel further on through a periodof sad neglect into a new role during the revolutionary years as part of the Navalforce which amassed in New York Harbour in 1776.

I was quite carried along by the tale of this doughtyworkhorse, and really enjoyed Moore’s telling of the international political backdrop.

You don’t need to be a historian of sailing to enjoy this historyof an enlightenment hero of the seas.

#28

William and Catherine Nicholson's Twelve Children (UPDATED)

January 23rd, 2020share this

Image courtesy of Tawny van Breda via Pixabay

Rather frustratingly, William Nicholson Jr (1789-1874) refers to a book in which the births of all the Nicholson children are listed ‘in minute detail’ – I wonder if this still exists?

Meanwhile, I think it might be a good idea to share what Ido know, and maybe someone else might stumble across this post one day and be ableto help complete the picture.

Sarah Nicholson

Born 21 February 1782

Married John Edwards RN, 2 October 1811

Died 7 March 1866, Torpoint.

Ann Nicholson

Born 20 April 1784

Died 22 March 1874, Plympton

William Nicholson

Born 15 March 1786

Bapt 9 April 1786

Died in infancy

Robert Nicholson

Born c1787

Died May 1814, Calcutta / Bengal.

Mary Nicholson

Born 28 November 1787

Married to Hugh Macintosh (1775-1834) on 31 December at Fort St George,Madras, India.

Gave birth to William Hugh Macintosh (1807-1840) on 27 December 1807

Died very soon after childbirth 1807/1808, India.

William Nicholson

Born 31 October 1789

Married Rebecca Brown, 18 August 1815

Son, John Lee Nicholson, born c1817

Died July 1874, Hull.

John Nicholson

Born c1791

Author of The Operative Mechanic andBritish Machinist.

Died in Australia (TBC).

Isaac Nicholson

Possibly born around 1793, if age 15 in 1808, when he was a midshipman aboard the David Scott.

Catherine Nicholson

Bapt 28 September 1794

Married Robert Hicks (1777-1832), 27 May 1813

Married Rev James Sedgwick (1794-1869) in 1838

Died before 1869

Charlotte Nicholson

Born 16 April 1797

Playmate of Mary Godwin (Shelley)

Married Henry Augustus Miller, 11 May 1815

Gave birth to Louisa Jane Miller, 1824 (Cuddalore?, East Indies)

Gave birth to Maria Miller, c1826 (India)

Married Richard Backhouse (?-1829), 15 January 1827

Died 7 July 1869

Martha Mary Nicholson

Born 24 May 1799

Baptised 4 July 1799

Playmate of Mary Godwin (Shelley)

This leaves one child still to be identified - Potentially a twin!

Carlisle and the Literary Fund save Nicholson from a pauper’s funeral

January 8th, 2020share this

Driving along at lunchtime today, Radio 4 reported on the number of public health funerals being paid for by local authorities at an average cost of £1,403.

Often called a pauper’s funeral, nowadays the local authority will pay for a basic burial when there is no family, or the family cannot afford to pay for funeral arrangements. There have also been stories in the media of people crowdfunding the cost of a funeral.

Neither of these were an option for Catherine Nicholson,when her husband William died at their home in Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury on Monday 21May 1815.

Their eldest son had left home to work in North Yorkshire, for Lord Middleton, but described how ‘My brother remained with him to the last and Carlisle attended him.’

Old friend, and co-discoverer of electrolysis, Anthony Carlisle was at this time the Professor of Anatomy of the Royal Society and in this same year, he was appointed to the Council of the College of Surgeons where for many years he was a curator of their Hunterian Museum.

Nicholson reportedly drank nothing except water since he was twenty years of age, which Carlisle said was the cause of his kidney problems

Despite his sober approach to life and earning well above average for the time, there were also substantial outgoings for ‘a family often or twelve grown up people, adequate servants and a house like a caravansary.’

On the day of Nicholson’s death, Carlisle saw the impoverished circumstances of the family and appealed to John Symmonds at the Literary Fund (now the Royal LiteraryFund) to help:

‘Poor Nicholson the celebrated author, and man of science, died this morning. His family are in the deepest poverty, and I doubt even the credit or the means to bury him.’

I have set a person to apply to the Literary Fund, pray second that application and recommend it to their bounty to be as liberal as their affairs and their rules will permit.’

The next day John Symmonds voted through a grant of £21 for Catherine Nicholson in respect of Nicholson’s talents and industriousness, writing ‘I am extremely desirous that something should be done, most necessarily of that society’ … ‘As he neither prepared for his dispatch, you are written that no time must be lost’.

Once funeral costs were paid, £21 cannot have lasted long, and Catherine Nicholson moved to 11 Grange Street from where she wrote to thank the Literary Fund for ‘the generous respect they were pleased to have for her late husband's abilities’.

Nicholson was buried on 23 May 1815 in St George’s Gardens, Bloomsbury, one of the first burial grounds to be established at a distance from its church due to the growing problem of overcrowding in London graveyards.

#27

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal 334,813

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order